Since the beginning, people have looked up at the moon and wondered. Early gazers may have thought the Moon was inhabited or that it somehow played a part in our fate.

Polynesians of the Pacific said that the moon was a creator goddess named Hina, the Greeks believed the moon was the goddess Artemis, sister of Apollo, the Romans called it Luna, and the Japanese believed that the moon was a god with powers of clairvoyance. There was also the green cheese theory.

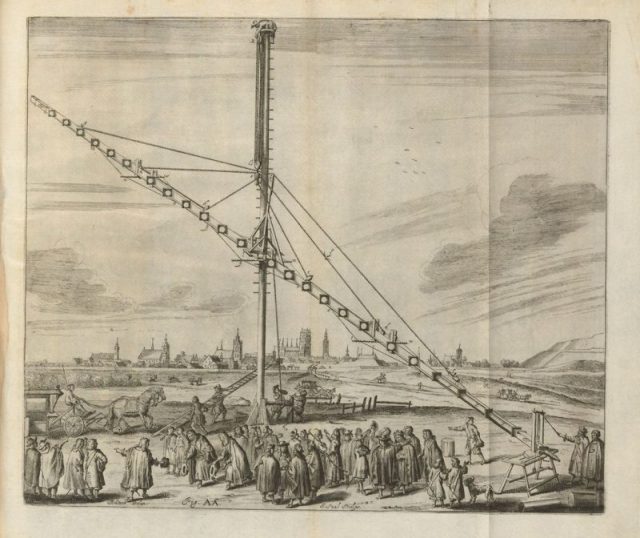

Moonlight was considered at one time to be dangerous and could drive one mad. According to a forum Myth Encyclopedia, in the 11th century, English philosopher Roger Bacon wrote, “Many have died from not protecting themselves from the rays of the moon.” Interest increased when Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius published the first atlas of the Moon in 1647 – all without the use of any high-powered telescopes. If fact he is considered the last astronomer to do major work without the use of a telescope. He eventually used a huge Keplerian telescope with a wood and wire tube he constructed himself.

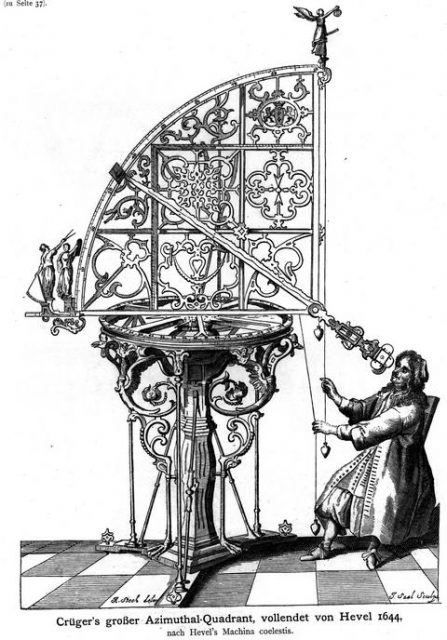

Hevelius, born in 1611 in Gdańsk, Poland spent his early years studying with German astronomer, mathematician, and polymath, Peter Krüger.

He was a brewer by trade and had studied law, but, upon the death of Krüger in 1639, Hevelius decided to become a full-time astronomer with his main focus on the Moon. Coming from a wealthy brewing family, he was able to put his full attention to his work. He built an observatory on the roof of his house and, later on, filled it with telescopes such as the large Keplerian telescope with a 150-foot focal length and other astronomy tools calling it Sternenberg or the “Star Castle.” However, even amidst pressure from colleagues to rely more on telescopes, Hevelius always maintained he could get just as accurate mappings simply with a quadrant and alidade.

His star castle became the go to place in Europe for stellar astronomy and was visited by the Polish Queen, Marie Louise Gonzaga; Polish King, John III Sobieski; and Edmond Halley of Halley’s Comet fame. King John was so impressed he allowed Hevelius and his family to run their brewery tax free to enable more resources for celestial study.

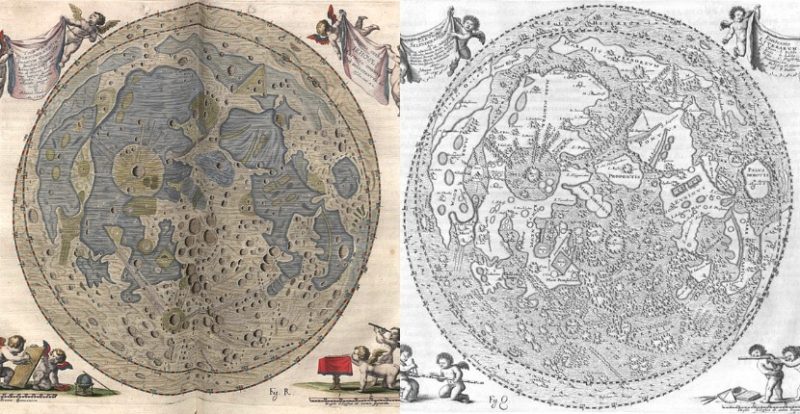

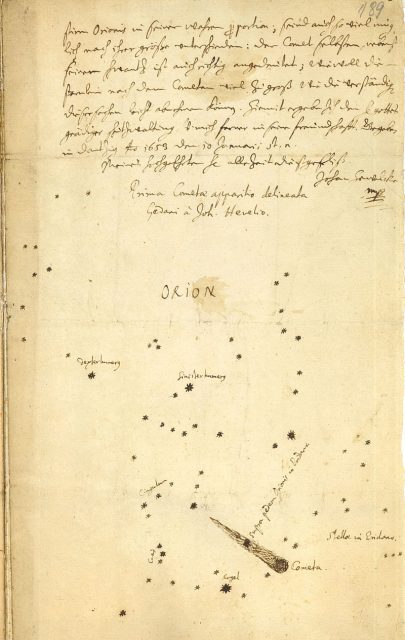

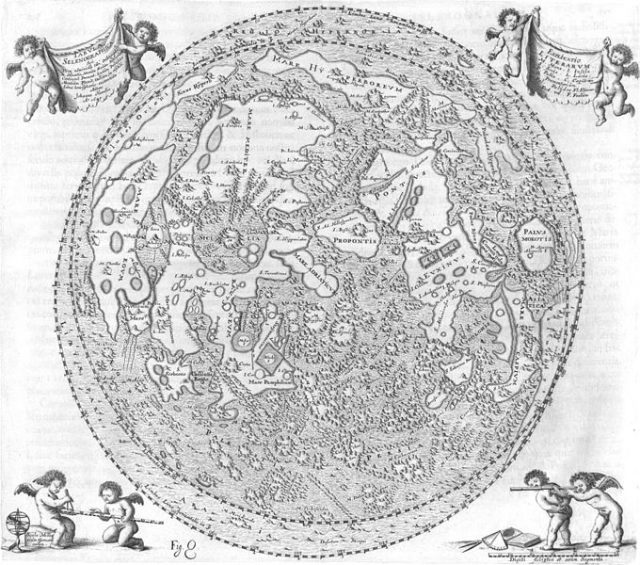

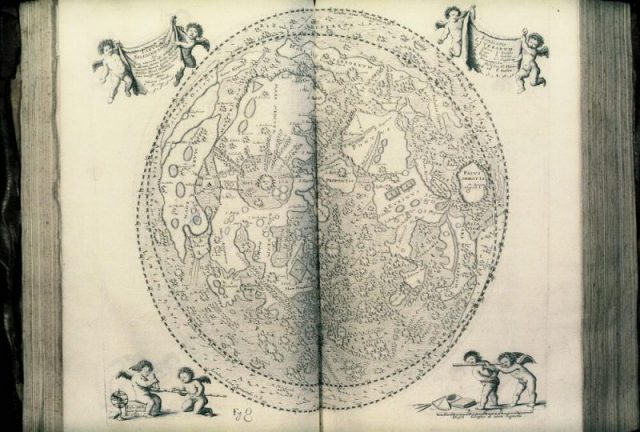

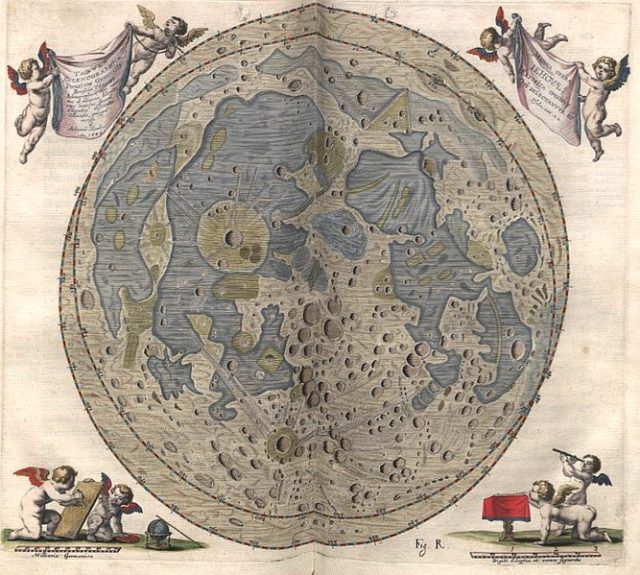

For several years, Hevelius sketched the moon every night and the next day engraved the images into copper for a print plate. In 1647, he published the nearly 500 page Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio (Selenography, or A Description of The Moon), complete with 137 pictures from the copper plates.

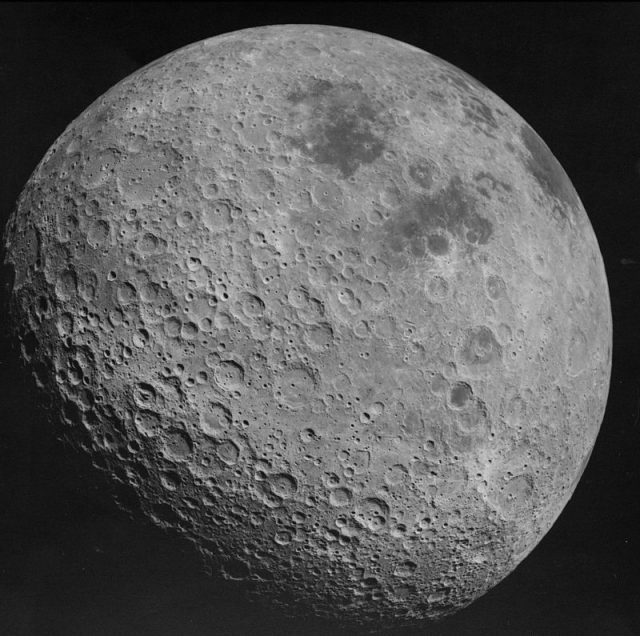

While he wasn’t the first to document the moon, his drawings contained more detail than anyone had seen before. He was the first to include the entire surface that is visible from Earth, and, from studying lunar eclipses, Hevelius was the first to determine how to map longitude. Astronomy historian Albert Van Helden tells us on CityLab that Hevelius managed the amazing feat of showing details of the moon in all phases in his engravings.

The book also contained three large plates, each showing the full moon in different ways: one view is as the moon looks through a telescope, one view uses geographical conventions like a mapmaker might use, and the third map is a synthesis illuminating all the lunar features.

According to Forbes, Pope Innocent X highly respected the book’s information, but he wished it hadn’t been written by a heretic (Hevelius was Lutheran). Hevelius named many of the landscape features, including a mountainous region called the Alps, and several of the names are still in use today, including a crater he named for himself.

Not only did Hevelius document the moon in great detail, he also discovered ten new constellations, identified four comets, and wrote several other books on astronomy. He built better and better telescopes, created star charts, invented the pendulum clock, and improved on the sundial.

Hevelius’s wife, Elisabeth Koopman, was a partner in his work and became an astronomer of some renown on her own merits. She published his star catalog in 1690, three years after Hevelius’s death; the catalog has been kept at Brigham Young University since 1971.

Read another story from us: 4 Billion-Year-old Rock from Earth Discovered on the Moon

Several copies of Selenographia sive Lunae descriptio still exist, including one in the Huntington Library near Los Angeles, another at the Hubble telescope observatory, and one in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. There were about 1,000 first editions printed that now command about $50,000 each.