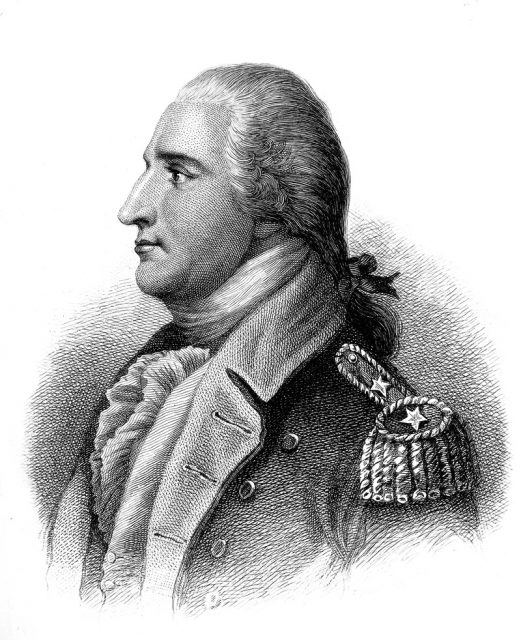

The name Benedict Arnold has become synonymous with the idea of betrayal, but how, exactly, did that happen? What did he do, and why did he do it?

Benedict Arnold was born in 1741, to a family whose ancestors were among the first to come to Rhode Island. Despite the fact that the Arnolds, as a family, were well established among the elite of that colony, Arnold’s father liked the drink a bit too much and moved his family to Connecticut. Young Arnold was desperate to escape the onus of being the son of such a man, and he left the family home in Norwich for the town of New Haven, where he worked to build an independent life and reputation, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

He became both a seagoing merchant and an apothecary, and by his mid-30s had established himself well and built a fine house, and a reputation to match. He became one of the first and most assertive patriots in New Haven, adding even more luster to his new life — although he stayed very sensitive about his upbringing, with a fragile ego that led him to several duels.

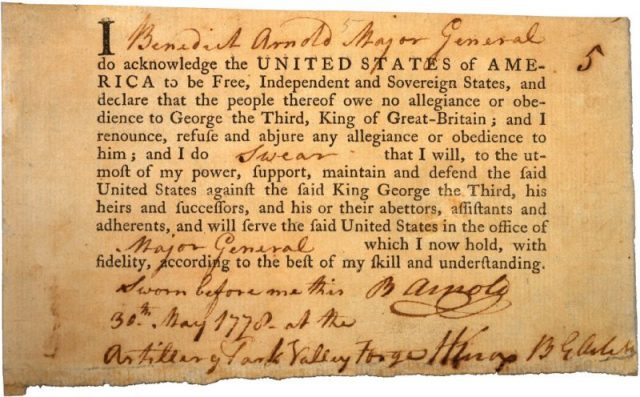

In April of 1775 he heard about skirmishes in Concord and Lexington, which led him to appropriate a portion of New Haven’s supply of gunpowder and take a company of volunteers to Cambridge. Here he convinced Joseph Warren and the Massachusetts Committee of Safety to let him take the supply of cannon and ammunition to Fort Ticonderoga.

Arnold wasn’t the only patriot who had conceived of the idea and, as a result, he ended up forming an uneasy alliance with Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, and taking the fort together. On their arrival, Allen and his men became more interested in divesting the fort of its supply of liquor than in the cannon, so Arnold and some of his company went across Lake Champlain, captured a couple of British military vessels, and put the lake under American control.

While he was gone he received word of the sudden passing of his wife, Margaret. Devastated, but not a man who could stay unoccupied for long, he sent his children to live with relatives and threw himself into the effort of liberating the colonies from British control, becoming an army officer under George Washington, and one Washington relied on heavily for the next several years.

At some point during those years, he met and fell in love with one Peggy Shippens, the daughter of a patrician family from Philadelphia who were, for all intents and purposes, Crown loyalists.

Despite the nearly 20 year difference in their ages and the broader differences between Arnold and the Shippens family with regard to politics, he was determined to make a marriage offer. He may not have had the same social clout as the Shippens’, but he was wealthy and looked like he was probably going to become even more so.

When the occupying British forces left Philadelphia, Washington assigned Arnold the task of remaining behind as a military governor over the city. Arnold remained, and took the opportunity to start rebuilding his wealth, which had taken a big hit during the course of the war. He entered into a series of somewhat shady deals as a means of re-establishing himself as a solid merchant.

Related Video: Last Survivor of Lincoln’s Final Night Goes on 1950s Game Show to Talk About It

By September 1778, Arnold still hadn’t amassed enough new wealth to make an offer for Peggy’s hand. Many among the city’s upper classes weren’t particularly enamored of the most fervent of the city’s Patriots, who were harassing them now that the British forces were out of the city.

Perhaps spurred on by not only his affection for Peggy Shippens but also by his continued need to get as far as he could from his unpleasant and rather impoverished upbringing, Arnold began to ingratiate himself with the wealthy of the city, and also to live a life of as much opulence as he could. This only served to drive the wedge further between himself and the other Patriots in Philadelphia at the time.

All of this earned Arnold a lot of dislike and distrust from the most dedicated patriots in the city. In particular, he was getting a lot of critical attention from an attorney named Joseph Reed, who was also known as one of the most radical of Philadelphia’s Patriots.

Reed had started out working closely with Washington, but for a variety of reasons was losing faith in him, and eventually left service with Washington to take a place as a delegate to Congress, then stepped down from that and starting prosecuting presumed Loyalists. He eventually became part of Pennsylvania’s Executive Council, using the power of his new position to further antagonize conservative Patriots and becoming ever more radical.

One of the steps Reed took was to start investigating Arnold, who was still a favorite of Washington. It was a clear show of power, both his state’s and his own, and it began to turn into his own personal vendetta.

Arnold did eventually marry Peggy Shippens, but only after borrowing a large sum of money to give her father as a settlement. It was just the beginning of his accumulation of debt, according to History.com, as he and his new wife proceeded to live a lavish lifestyle. As his debts increased, he began to feel more resentment that he wasn’t receiving promotions as fast as he felt he deserved.

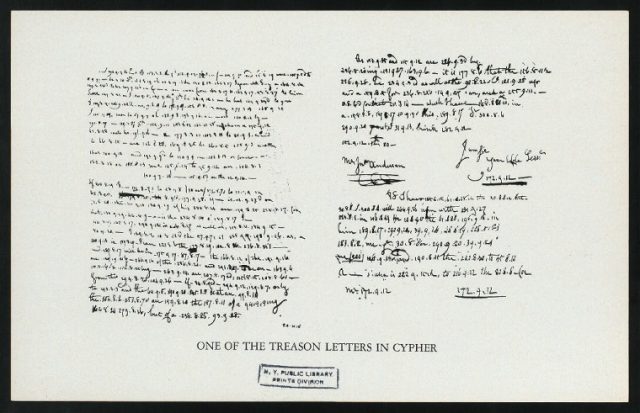

In 1780 Arnold was given the command at West Point, in New York. His bitter frustrations at feeling overlooked for promotion and underappreciated as well as his desperate desire for prosperity, this was when Arnold made his move. He contacted the head of the British Forces, Sir Henry Clinton, and offered him a deal. Arnold would give West Point to the British, along with its men.

In return, he would be given a great deal of money by the British government and a place of honor in the British Army. He would then have everything he wanted – wealth, a high standing in the military, and Peggy Shippens to share it with.

The plot, however, was discovered before it could be enacted, and at least one of the conspirators was killed. Arnold went to the British side, and led troops in actions in Connecticut and in Virginia before eventually moving to England. Even after he moved, however, he was never given everything the British promised him in exchange for his betrayal. He ended his days in London in 1801, reviled by the patriots of America, and largely invisible to the English.

Ultimately, it’s hard to say if Arnold, himself, believed that he was betraying his country and the freedoms that he valued, especially in the early days of the Revolution. It could well be that he felt that the Revolutionaries internal political struggles, such as the divisions being created by men like Reed, were tearing apart any real chance of reaching their goals.

There is certainly reason to believe that Arnold increasingly came to feel that the country he had committed to so fiercely at the outset had let him down.

Read another story from us: Deborah Sampson – The Disguised Revolutionary War Fighter

Although his name comes with associations of rank betrayal, his situation was more complicated than that. His actions came from a complex mix of insecurity, selfishness, love (or perhaps infatuation), disillusionment, financial struggles, and, perhaps, even a conviction that what he was doing was in the best interest of his mother country. While none of that will excuse him in the eyes of history, it may make what he did a little more understandable.