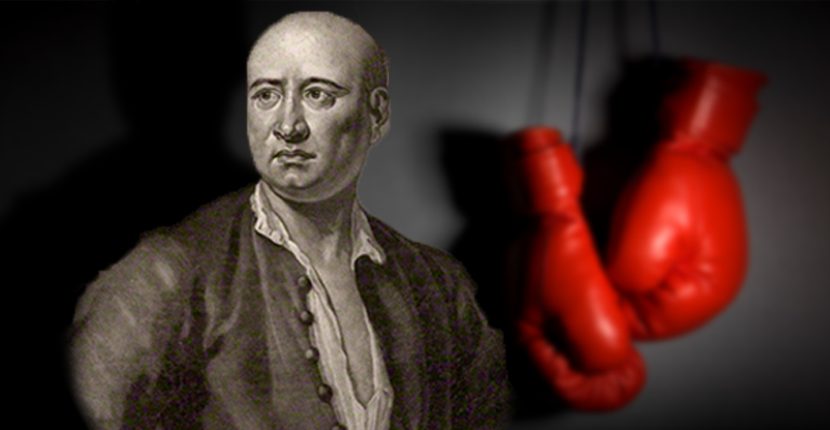

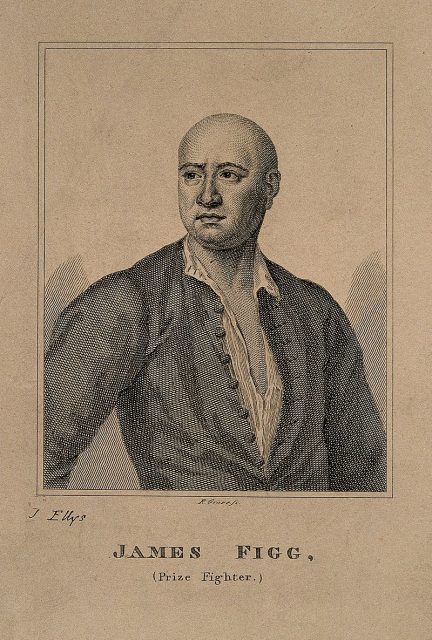

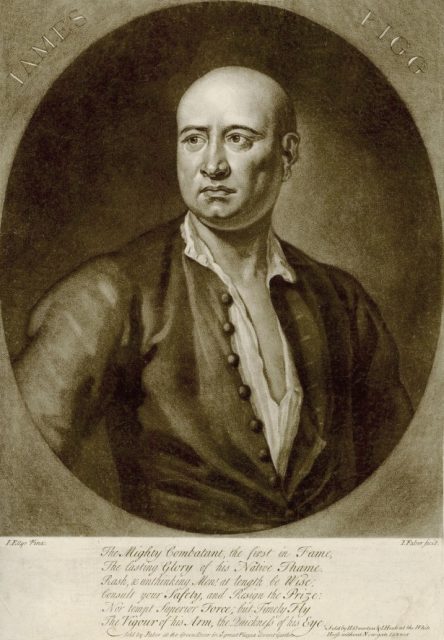

One of the forgotten figures in boxing history is James Figg, an Englishman of the early 18th century who is credited with being the man to lay the foundations for the modern sport, though he fought before the introduction of the rules devised by John Douglas, better known as the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, which in many ways still govern boxing today. Still, Figg is considered by most to be the first heavyweight boxing champion who has earned the moniker “Father of Boxing”.

However, combat sports fans might recognize the boxing matches of the era as being more like today’s MMA bouts than modern boxing – holds, throws, kicks and chokes were allowed – if they had been agreed upon before the match. James Figg was not only a boxer, but was accomplished with the saber, the cudgel and the staff, and regularly engaged in bouts with all of them.

Those of you familiar with the film Rob Roy (1995) will know that the “manly”, or “combat arts” were past-times for the rich and aristocratic, who would bet money, land, castles, women and much else on their man. Most fights, unlike the ones in the film, were not to the end, but serious injury and at times fatalities occurred at an alarming rate. The combatants knew the risks, but the purse and the reputation for the winners made it worth it to many.

Figg was born in 1684 in Oxfordshire and began his fighting career there. He came to the notice of the Earl of Peterborough, a betting man, who was described in the newspapers of the time as a “staunch patron of all brave and manly sports.”

In a way, Peterborough and others like him were the 18th century equivalent of today’s boxing promoters. Though fighters could make money traveling the country on their own, challenging local or national toughs, the big money was made by finding a patron, much like the painters and sculptors of the time.

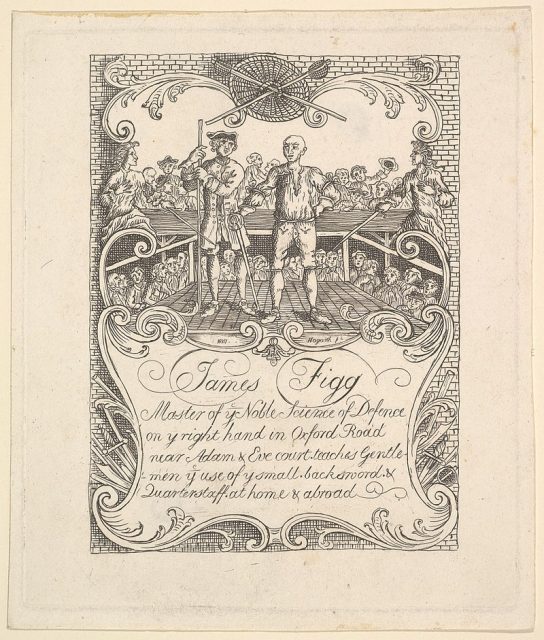

Figg was 6′ tall and weighed 185 lbs – very small for a heavyweight today, but at the time, considerably bigger than the average man. In addition to making money from fencing, staff fights and boxing, he opened an academy where he tutored the sons of the aristocracy in sports. By all accounts, he did not take it easy on them.

By his early 20s, Figg had a national reputation and his matches were attended by the stars of the day – meaning the aristocracy. People traveling back in time might recognize the venues of Figg’s (and others) matches. Vendors selling food and ale, musical numbers before and after fights, and even traveling “bawdy houses” were on site.

In his lifetime, Figg fought 270 combat matches. At least, those are the ones that were recorded. These were not fought with protective gear, and scores were kept by wound, or with a man bowing out because he could not go on physically, mentally or both. Sometimes they died. In 1730, while he was heavyweight boxing champion, Figg fought a duel which forced the other man to quit because Figg had almost cut off his hand at the wrist.

Many of the matches that Figg took part in were a combination of boxing, fencing and stick fighting. Sometimes, rounds would alternate: 1 round boxing, 1 fencing, 1 staff and so on. The boxing matches, as you can imagine, were bare-knuckle, and most of the matches did not have a round limit, unless set before the fight. That meant that the men went on until one could no longer go on, or quit.

In 1725 he was challenged by one Ned Sutton and lost – the only loss of his career. In one of combat sports first noted and publicized rivalries, Sutton, a pipe-fitter and nationally recognized fighter, and Figg called each other out and their fans fought in the streets. In many ways, Sutton vs. Figg was much like the Ali-Frazier fights of the 1970s.

In the first fight, Sutton beat Figg, giving him his only loss. The rematch came two years later, on June 6, 1727. The first round was to be fought with swords. Sutton moved with such speed that Figg missed a swing and cut his own arm, but that was not near enough to end the fight. The rest of the round belonged to Figg, who wounded Sutton in the shoulder when the round was declared over. They then went back to their men, had a cold ale, and got ready for the next bit.

The second round was when the boxing began. Imagine Floyd Mayweather or Manny Pacquiao coming out to fight round two with a sword gash in their arm. When the round began, the two men went at each other viciously, though by all accounts, they struck mostly with their fists, despite the fact that kicks were allowed, even on a downed opponent. Eye gouging was OK too.

It seemed as if Sutton might win again when he hit Figg in the body, knocking him from the elevated stage they were fighting on, but Figg came back and used speed and an amazing number of punches to wear Sutton down, until he beat him to the ground, and then jumped on him, tying him up until it was agreed round three would begin.

After all of that, round three was fought with cudgels, and Figg was especially good with them – he broke Sutton’s kneecap and the fight was over. Figg was feted throughout England.

Related Video: Sylvester Stallone Turned Down a Fortune to Play Rocky

https://youtu.be/hmrbvvuCSYk

He fought one other fight before retiring and going into promotion himself. This was with a massive Italian gondolier who had been seen fighting three men at once by a vacationing British earl, who offered him a large amount of money to come to England and beat James Figg. The fight didn’t last one round – Figg knocked him out almost instantly.

Figg died at the age of 42, which, considering the average lifespan of the time (1734), and the punishment he had taken, was actually quite a long life. James Figg lives on in the art of famed artist and satirist William Hogarth, who pictured the fighter and his fights in a number of his works.