The grim legend of A Clockwork Orange and its anti-hero Alex the “droog” lives on, thanks to a surprise discovery amongst late author Anthony Burgess’s papers.

A follow up work titled A Clockwork Condition reached 200 pages before being abandoned. However those wanting to know about Alex’s future may be disappointed.

The non-fiction project focuses on exploring the novel’s themes of “ultraviolence” and the effect of outside stimulus on society rather than continuing the narrative.

The powerful story concerned a terrifying teen, whose leadership of a gang of destructive delinquents led to him becoming part of a groundbreaking and horrifying experiment at the hands of the state. They attempted to reform him but their brutal efforts failed.

Smithsonian.com writes A Clockwork Condition is “not a sequel to the cult novel (published in 1962), but rather a meditation on the ‘condition of modern man’ that was to be structured similarly to Dante’s Inferno.” These lofty comparisons are apt — despite Alex’s penchant for brutality, he also loved the finer things in life such as Beethoven.

The manuscript, part of which is handwritten, has been found by the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester, England. They took possession of a wealth of documents after his death in 1993 and have been studying this invaluable archive.

Other items in the collection include dozens of unpublished stories together with a slang dictionary, a monster of a task which Burgess attempted to compile before giving up.

The writer was preoccupied with modern words — so much so, that in A Clockwork Orange Alex and his unruly pals speak a made-up language called “Nadsat”. Burgess reportedly used this so his text wouldn’t seem outdated.

The original plan for A Clockwork Condition was that “the book would be illustrated with surreal photos and quotations from famous writers discussing freedom and the individual.”

Prof. Andrew Biswell — the Foundation’s director — says the volume was ditched owing to Burgess ruling himself unsuitable for philosophical work.

In fact Biswell believed the sequel was a fantasy of sorts, following information he’d read previously. Quoted by Smithsonian.com, he reveals “I’d come across a reference to The Clockwork Condition — just one reference — in an interview from around 1975, where Burgess was asked, ‘Where is this book?’ And he said, ‘Oh God, that will never be published. That doesn’t really exist’.” To Biswell’s surprise, it did.

A key revelation in the text is the story behind the novel’s unusual title. The BBC reports Burgess overheard the expression “as queer as a clockwork orange” being used by an ageing Cockney. He kept it in mind for two decades before finally finding a home for it.

The writer referred to the half-sequel “as a ‘major philosophical statement on the contemporary human condition’, outlining his concerns about the effect on humanity of technology, in particular media, film and television.”

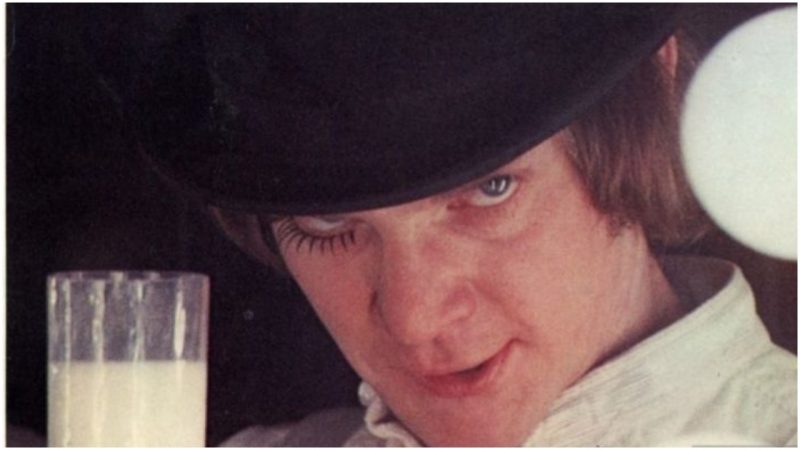

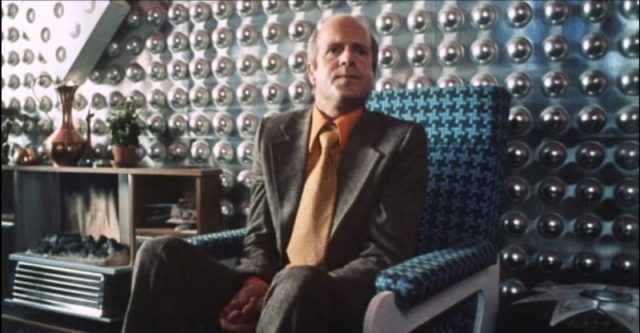

The film had a particular bearing on the saga. In 1971 director Stanley Kubrick brought A Clockwork Orange to the big screen, starring Malcolm McDowell as Alex. The movie’s brief but shocking depictions of violence led to Kubrick pulling the UK release. This was after links were made between real-life cases and the film’s content.

Writing for the Guardian 20 years after Kubrick’s death, McDowell says, “The intelligent newspapers would write editorials about it, not only reviews. It was bigger than just a movie, because everyone latched on to the issue of gangs and violence in society.”

The actor experienced gruelling treatment at the hands of perfectionist Kubrick, who reportedly put his sight at risk during the infamous “Ludovico technique” sequence. Having said that, he regards the end product as a career highlight.

“Doing this film has put me in movie history,” he writes. “Every new generation rediscovers it – not because of the violence, which is old hat compared to today, but the psychological violence. That debate, about a man’s freedom of choice, is still current.”

Read another story from us: Why ‘A Clockwork Orange’ was Banned…by Stanley Kubrick Himself

Burgess’s 1974 novella The Clockwork Testament wound up exploring similar themes. While he may not have chosen for A Clockwork Condition to be published, it provides a fascinating insight into what drove one of the most distinctive novels of the twentieth century.