We don’t tend to connect beetles and museums. We tend to think of museums as homes for great art, sculptures, and displays of historical significance. Some show items related to the natural world, like the Natural History Museum in New York. But Chicago’s Field Museum is in a league of its own, with more than 40 million objects and specimens.

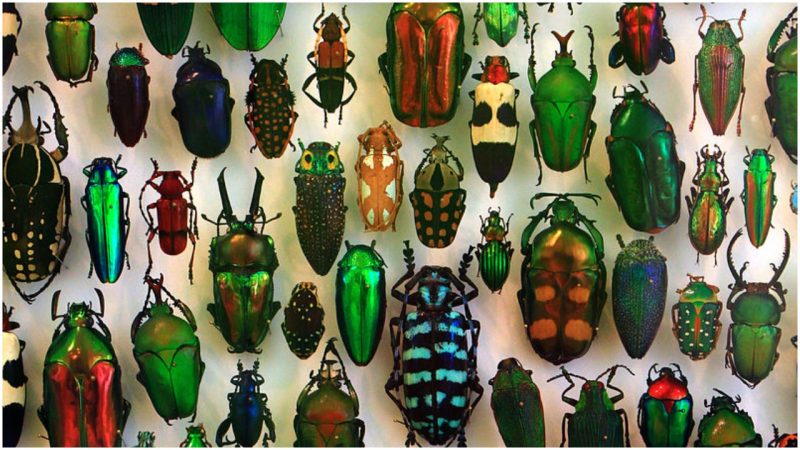

The Field Museum is home to six special collections: amphibians and reptiles; mammals; birds; insects, arachnids and myriapods; invertebrates; and fishes. In total, staff tend to almost 20 million species from around the globe.

The Insect Division alone includes more than 12 million specimens, more than half the museum’s complete collection of critters.

The Museum got its name back in 1905 when department store magnate, Marshall Field, donated $1 million to establish it, a considerable sum back then.

Today, staff don’t just supervise the collections — they work to educate everyone from kindergarten kids to PhD candidates to the general public on our natural world.

Not all of the specimens that end up at the museum are alive. And a lot of these, while preserved in some way, arrive in a horrible-looking condition that would terrify visitors if they were displayed “as is.” That’s where a particular room on the third floor of the building comes in.

Behind two sets of heavy doors, out of view of the public, is an area devoted to dead things – specifically, dead mammals that have made their way to the museum, usually by way of donation.

The section includes little critters like chipmunks all the way up in size to large ones like leopards and buffaloes; even a dead sea lion arrived once. It is the task of the staff behind these double doors to strip the flesh from these creatures and get them ready to show.

That “staff” consists of thousands, perhaps millions (no one is sure of the precise number) of flesh eating beetles. A carcass is deposited in their path, and, depending on its size and state of decomposition, it is stripped within a couple of days or a couple of weeks. Then, once the beetles have gorged themselves, they up and die.

But beetle labor is the most efficient, natural way for these specimens to be made ready for guests to see. And the beetle is just doing what it does.

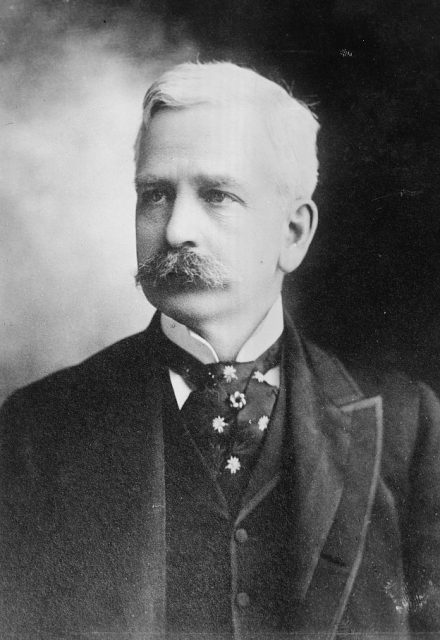

Anna Goldman is in charge of the beetle brigade. Although her job description is one that would make most people’s skin crawl, Goldman is an enthusiastic supporter of her small charges and the work they do. “They have personalities!” she said in an interview a few years ago with the Chicago Tribune. “Some want to fly. Some are slow. Some are curious. When they end up on my hand, I swear they lean back their heads and look up at me.”

Although every item at the museum is catalogued and documented, the origin of the beetle colony and how it arrived is a complete mystery. Goldman confirmed that the Field Museum’s beetle colony is “wildly successful.”

Usually, colonies of beetles in museums die off eventually. This colony is around 60 years old and continues to repopulate. The museum has not needed to add new beetles to it over the years; they seem to just replicate themselves, then die off in a wholly natural cycle.

While the idea of countless beetles roaming the halls of the Field Museum sounds like the premise of a good old-fashioned horror film, and the odd one has escaped, there is no risk to the public, Goldman explained.

They only eat dead things – anything alive puts them off. Their taste buds are even more discerning than that; they don’t care for fish, and absolutely despise possum. And they aren’t averse to a little drink once in a while,” Goldman said. “We have a researcher who preserves specimens in hooch,” she said, “and the beetles love it.”

Read another story from us: Two Antique Portuguese Libraries Use Live Bats as Insect Repellant

Anyone else might be completely put off at the idea of spending their days surrounded by flesh-eating beetles in museums, but Goldman loves her job and her beetles. They don’t scare her at all, because she admires them. “They have tiny mouths that can chew into places in a body you would never imagine,” she explained. She’s convinced her beetles know and like her enormously. “But of course, if I were dead, they would like me more.”