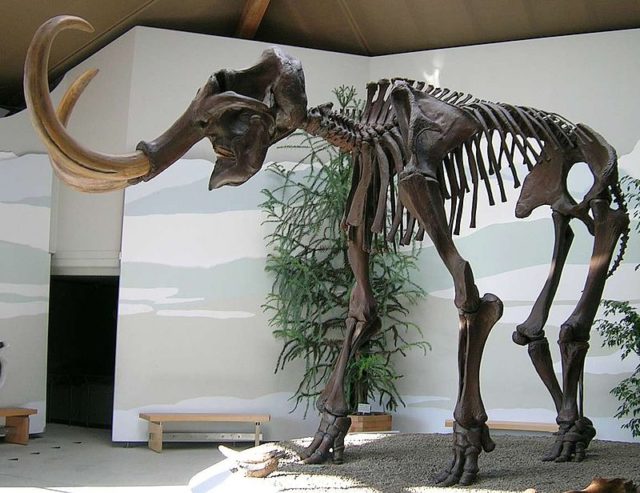

Over the millennia, many species, such as woolly mammoths have risen and then fallen into extinction, but modern researchers often have a hard time figuring out what the catalyst was for a particular extinction event. Newsweek recently reported that a new study has shed light on how the woolly mammoth may have finally and completely disappeared.

The woolly mammoth had a relatively long period of decline, vanishing from one area at a time over the span of thousands of years. Mammoths disappeared from Russia about 15,000 years ago; however mammoth populations on St. Paul’s Island in Alaska didn’t die out until about 5,600 years ago. The mammoth population on Wrangel Island, a small island in the Arctic Ocean, is believed to be the home of what was the last existing population of woolly mammoths, which only died out about 4,000 years ago, at the same time as the Great Pyramids of Egypt were being built.

The mammoths of Wrangel Island lived in isolation, removed from human hunters, under fairly stable weather conditions for at least 7,000 years. Given that the animals were exempt from many of the factors that caused populations in other areas to die out, researchers wanted to figure out what pushed the mammoth population there past its tipping point.

Researchers analyzed the mammoth’s diet, metabolism, and nutrition and didn’t find much that would put the animals under stress. That strongly suggests that the last mammoths went extinct due to some sort of catastrophic weather event, which caused a large number of them to die of starvation.

Lara Arppe, from the Finnish Museum of Natural History, was one of the people involved in the study. She said that no one had ever really looked at the dietary ecology of Wrangel Island mammoths and, since there had been other examinations of extinct species related to diet, the researchers felt it was high time to give it some study. The goal was to examine the dietary ecology to see if there were any indicators of malnutrition or starvation.

They did their study by comparing bones and teeth from Wranglian mammoths with those of mammoths from other areas, paying attention to the carbon and nitrogen isotopes that provide information about nutrition and metabolic function in the thousands of years prior to the mammoths’ extinction. They published the results of their research in Quaternary Science Review.

To summarize, what they found was that there were no signs of the Wranglian mammoths having a slow decline. When their numbers dropped, they dropped quickly. Arppe described it as being like the population hit a wall.

Her team found that, in general, that population’s dietary requirements were a lot like those of the Siberian mammoth but with a few important differences. One of those variations was that the Wrangel Island mammoths seem to have used fats as a dietary resource in a different way from other populations. They relied on fat reserves to help them survive bitter winter conditions in a way that animals who lived in slightly warmer climates didn’t need to.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0W05zqydFsE

Given that information and the fact that there hadn’t been any long-term changes to the habitat, Arppe and her team concluded that the most likely cause of the mass extinction was a severe, short-term, weather event, such as icing events in which rain falls on the snow creating an ice barrier that prevented the mammoths from reaching the food they needed. In short, the Wrangel Island mammoths most likely starved into extinction.

Weather events may have also limited the mammoths’ access to sources of fresh water, which is the next area the group plans to study. Currently they hypothesize that the surrounding bedrock may have periodically released natural chemicals into the water supply which could be harmful, or even toxic, to the animals who drank from it.

In 2017, a report from the BBC also talked about some reasons for the population’s collapse, noting that studies had suggested that the last mammoths’ DNA had become severely compromised and riddled with errors, causing a “genomic meltdown” around the same time the animals on the island went extinct. It’s certainly true that any group which lives in isolation has a very limited gene pool to reproduce from, and unhealthy mutations could become increasingly common over time.

Related Article: Scientists Reawaken Cells from a 28,000-yr-old Woolly Mammoth

If the mammoths were already stressed at a genomic level, then a climate catastrophe of the type suggested by Arppe’s research would have an even more devastating effect.

Whether it was starvation, genetic collapse, or a combination of both, it was enough to put an end to the last woolly mammoths on the planet.