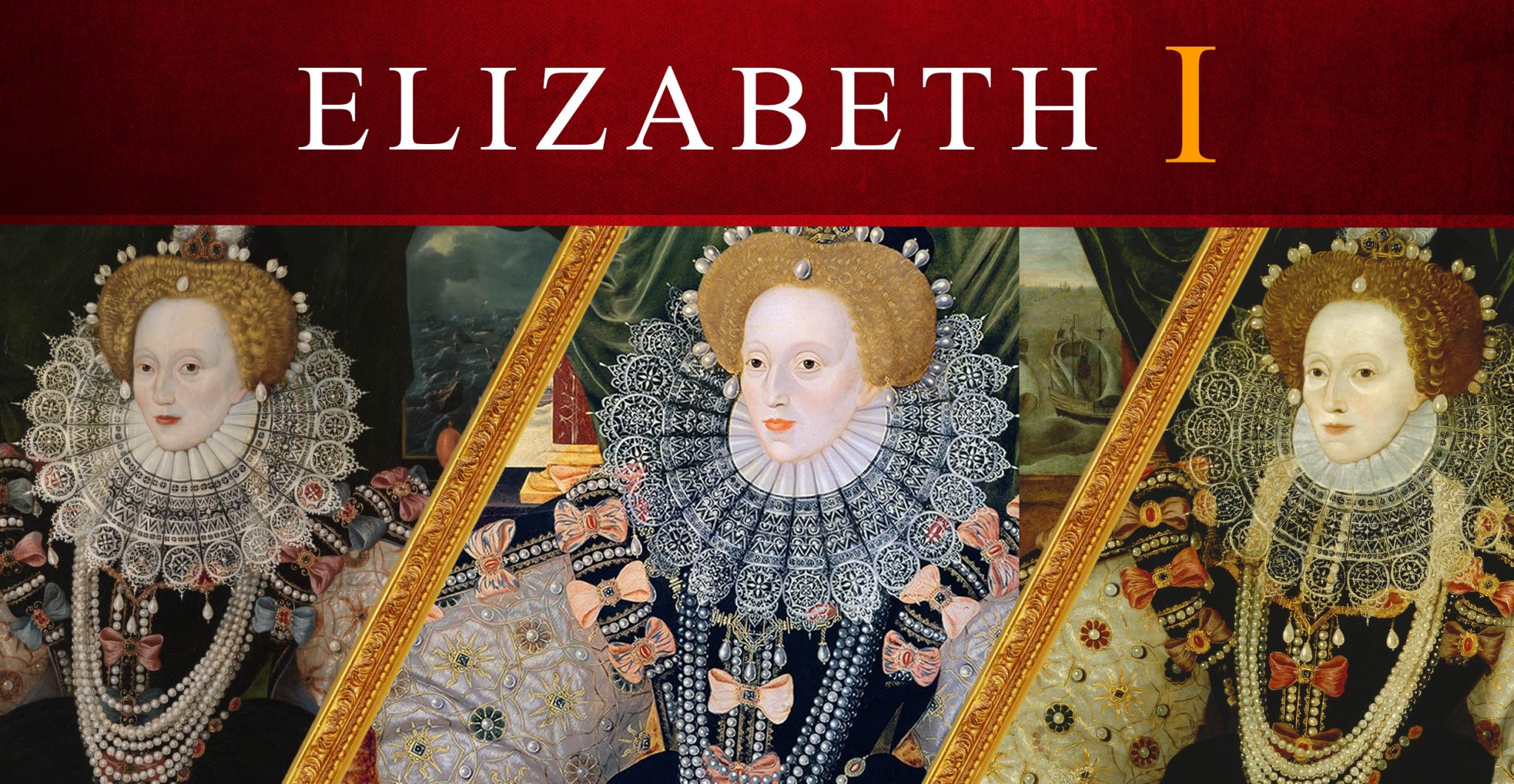

In February of 2020, three surviving portraits of Queen Elizabeth I painted after the victory of the battle with the Spanish Armada will go on display at the Queen’s House in Greenwich, London, the birthplace of Henry VIII in 1491, his eldest daughter Mary I in 1516, and his second daughter, Elizabeth I in 1553. Royal Museums Greenwich recently announced the showing, the first time all three paintings have been displayed together, will be titled Faces of a Queen: The Armada Portraits of Elizabeth I.

The three portraits of England’s Queen are believed to be the work of George Gower who became Serjeant Painter to Queen Elizabeth I in 1581, according to Tate Collective. It was fairly common to paint duplicates as it was the only way to copy paintings for sale, or for multiple patrons, and reduce forgeries.

Two of the portraits are on loan from the National Portrait Gallery in London and Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire while the third is already in the collection of the Royal Museums Greenwich after a frantic fundraising effort to keep the painting from being bought by a private collector and perhaps hidden away for generations. The family of Sir Francis Drake was the original owner of the depiction offered for sale in 2016, and Drake may have commissioned it himself.

The Woburn Abbey portrait, on loan from Henrietta Russell, Dowager Duchess of Bedford, is the only complete painting as the others appear to have been cropped at some point. It features the Queen seated in front of scenes from the battle of the Armada with her right hand on a globe with the Americas in view to represent the imperial intentions of Drake and the Queen, and she holds an ostrich fan, a symbol of truth and purity, in her left hand.

Her sumptuous, puffy gown is covered in fine jewels and pearls. She wears several strands of pearls around her neck and some in the fiery auburn hair she inherited from her father. The pearls, favorites of her mother Anne Boleyn, represented chastity.

Elizabeth knew the power of her image and, according to Smithsonian.com, a representative of the museum stated, “The Armada portrait composition is a prime example of how portraiture was used to control the public image of Elizabeth I presenting her as a powerful, authoritative and majestic figure.” Historians believe the Armada portraits were some of the few paintings Elizabeth actually sat for, and everything but her face and hands were painted before the sitting.

According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, in 1588 the Spanish Armada, Spain’s military fleet of about thirty ships and eight thousand seamen, was sent to invade England by King Philip II of Spain to not only bring Catholicism back to England but to avenge the raids committed by Sir Francis Drake in the Caribbean in the mid 1500s.

The fleet was commanded by Alonso Pérez de Guzmán, duke de Medina-Sidonia who had recently replaced the late Álvaro de Bazán de Marqués de Santa Cruz. Phillip liked Medina-Sidonia so much that he appointed the Duke to command the fleet although Medina-Sidonia protested that he had neither the experience nor enough knowledge of the sea, which ultimately caused the Spanish to lose the battle.

The English fleet was commanded by Charles Howard, second Baron Howard of Effingham with Sir Francis Drake as second in command. There were about the same number of ships, but the smaller English ships were quick and were outfitted with heavier guns.

The English were able to pester the Spanish fleet from long range until they finally launched eight fire ships filled with flammable materials which were set on fire and allowed to drift into the Spanish ships. The Spanish quickly cut their anchors and sent their boats further out to sea, breaking their formation.

SEE: Altar Cloth Turns Out to be Only Surviving Dress of Queen Elizabeth I

The English broke through with bigger and more efficient guns, sinking three Spanish ships and damaging many more. The remaining Spanish ships turned and fled back to Spain by way of the North Sea of Ireland, suffering even more losses during the voyage due to bad weather, damage to the ships, lack of supplies, and being driven into rocky coasts by the wind. Only sixty ships made it back to Spain with the loss of possibly fifteen thousand men.