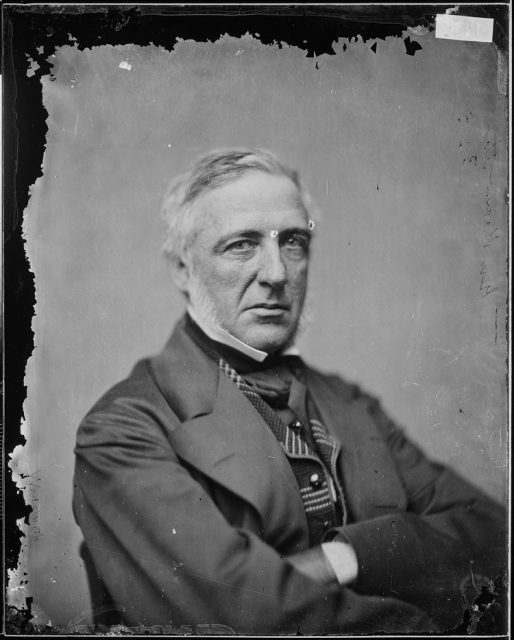

The most famous photographers of Civil War portraits were Matthew Brady, Alexander Gardner, and Timothy O’Sullivan. They loaded their photography equipment into their wagons and followed behind major battles making images for the public who were able to see real soldiers for the first time. While they may have been the most famous, there were plenty of photographers delving into the new medium by following armies around and setting up studios on the field to capture portraits of soldiers to be sent home to loved ones.

Archaeological excavations focusing mainly on William Berkley’s general store in Camp Nelson in Nicholasville, Kentucky have revealed the remains of what is perhaps the first permanent photographic studio for soldiers. It was set up one hundred and fifty years ago in the Union camp. Archeological study of the studio has produced stencils, which were used as framing mats are today, marked as created by Cassius Jones Young.

Of the many items recovered, several bottles caught the eye of Dr. Stephen McBride, the Director of Interpretation and Archaeology, Camp Nelson Civil War Heritage Park, Jessamine County, Kentucky and his team. Originally believed to be medicine bottles, the team pieced them back together and discovered they were bottles with lettering identifying them as “Christadoro” and “Dr. Jaynes” which turned out to be brands of hair dye.

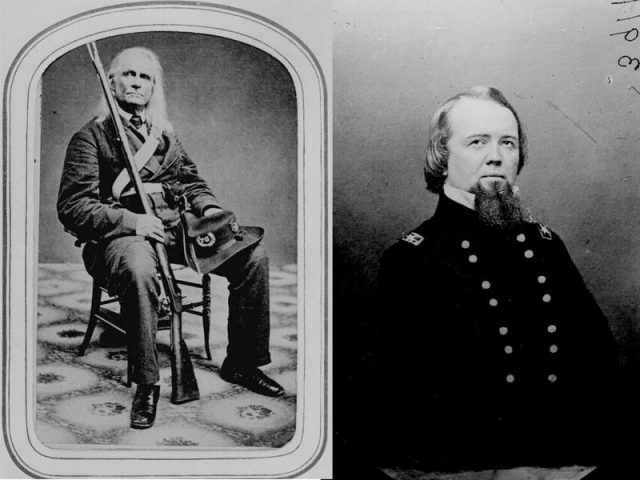

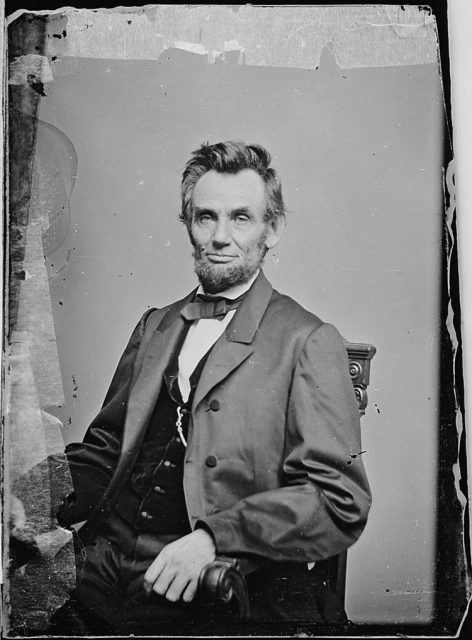

It is believed that, because of the photographic methods used at the time, the black and white photographs caused light hair to look white or gray. Not wanting to be washed out in the picture, and perhaps a bit self-conscious of premature gray hair due to the obvious stress of their life during the conflict, many men combed the dark hair dye through their hair and sometimes their beards before sitting for the portrait. According to Newsweek, the Director of the Center for Civil War Photography, Bob Zeller remarked, “…now we have an archaeological discovery of a Civil War photo studio. As far as I know, it has not happened before.”

Photography of the 1800s was a far cry from the modern cell phone cameras that capture action and produce a photo instantaneously. Cameras were large and bulky boxes that needed tripods and dark hoods for the photographer to capture a good image.

According to American Battlefield Trust, toxic chemicals were used on site in small, dark wagons to prepare the plate glass used to capture the image with collodion, which contains sulfuric acid, as well as coating the plate with silver nitrate, and then the image was developed with pyrogallic acid. Once the glass was loaded into the camera in a light-proof jacket, the photographer removed the cap from the camera lens and the light imprinted the image on the glass.

One of the reasons most people didn’t smile was because no one could move while the cap was off the camera, and it would take so long for the image to imprint that rather than try to hold a smile it was easier to hold a straight face. Photographing babies and animals was especially difficult. Once the cap was put back on the lens, the plate was taken to the darkroom in the wagon and placed in the pyrogallic acid and left to develop. The plate was then painted with varnish and used as a negative to make pictures. Because of the delicate and dangerous process, photography was left to professionals.

Finding a permanent studio near Camp Nelson was not a complete surprise. From June of 1863 until the end of the war, Camp Nelson was used as a U.S. Army Supply Depot and was home to over eight thousand soldiers on four thousand acres of land, according to Newsweek.

It was practically a town in itself as, in addition to the barracks, it included a hospital, prison, bakery, sawmill, and butcher. Sutlers, merchants who usually followed the larger armies in wagons, set up shops selling leather goods, fruits and vegetables, and soldiers’ personal needs such as cups, dishes, combs, and the like.

Related Article: Unknown Civil War Faces are Being Identified Through Facial Recognition App

They were joined by the photography studio and a post office. It was a bustling recruitment center after 1864 when contraband slaves were permitted to join the Union army and win freedom for themselves and their families, and it became a refugee site as more and more slaves came for help.

Camp Nelson is now managed by the National Park Service and was declared a national monument in October 2018.