Human origins and evolution seem to take leaps and strides every year, and 2019 was no exception. When the year is drawing to a close, it’s pretty common for various media sources to do pieces that are retrospectives of the last 12 months. Topics can range from current events to pop culture, but sometimes those pieces cover meatier topics. Smithsonian, for example, chose to do a piece about what we’ve learned about the origins of human beings. Here are some of the things 2019 taught us about human evolution.

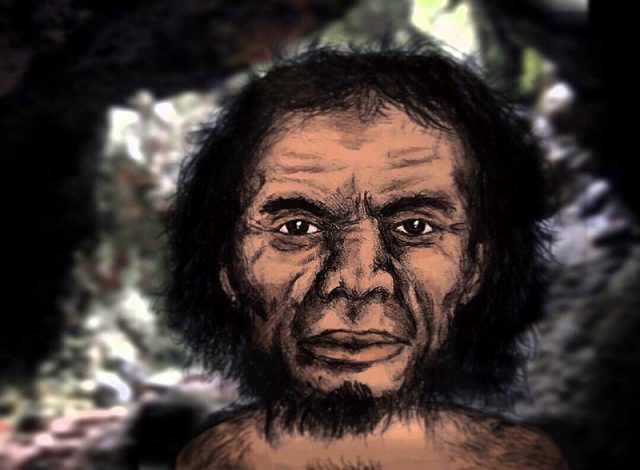

Homo Luzonensis

A new version of early man was discovered. Human evolution isn’t really a straight-line process. There have been a lot of twists and turns, with different species rising and dying out after making their contributions to the gene pool. One of those species was only identified this spring. A team of scientists made the determination after looking at bones and teeth which came from the remains of two adults and one child, and which were found in a cave on the Philippines island of Luzon.

The bones are somewhere between 50,000 and 67,000 years old. The species has been named Homo luzonensis, and would have been alive at the same time as other, better-known species, including the Neanderthals and even Homo sapiens. The species physical characteristics suggest a blend of both more ancient versions of man and those that were currently around, which makes scientists wonder if this species could mean that hominids migrated from Africa earlier than we thought.

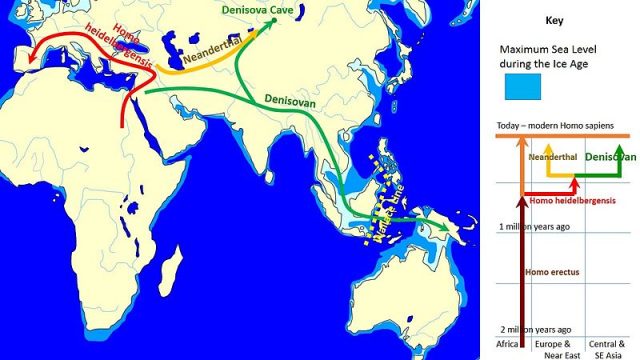

DNA of Denisovans

The DNA of another relatively newly-discovered species has shown up in modern humans’ genomes. The wonders of DNA analysis have allowed researchers to learn all sorts of things about how humanity developed. Nearly a decade ago researchers were analysing fossils from a cave in Siberia that had been used by both Neanderthals and modern humans.

They managed to obtain mitochondrial DNA from the fingerbone of a female set of remains and discovered she was neither one, but rather came from another, now extinct species. The species have been called Denisovans, in honor of the cave it found in. Since that discovery, it’s been learned that Denisovans interbred with both Neanderthals and modern humans.

This spring, another study showed that there were Denisovan genes present in modern human genomes in 14 island groups in New Guinea and Southeast Asia. Specifically, the study showed that humans interbred with at least three different Denisovan groups who were spread over a wide geographical area. That suggests that what have all been called Denisovans is, in fact, at least three different, genetically diverse groups.

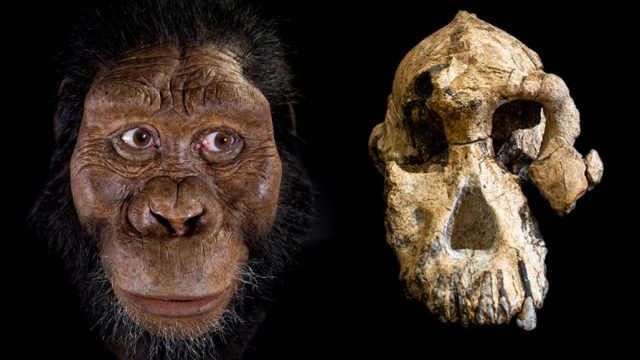

Australopithecus Anamensis

Australopithecus anamensis has been around for a while, the species having been named back in 1955, but was only known by a few of its bones, namely its jaws, teeth, and some post-cranial bones. The species was found in Africa, and the bones were close to 4 million years old. There also had never been enough of them found to allow scientists to get an idea of what these early humans actually looked like.

That changed in September, when a team of scientists working in Ethiopia found a nearly intact skull from this species, allow us to finally get a look at its face. The skull was very well-preserved, and is the earliest-known version of its species. The skull’s age shows that the species overlapped in time with the existence of Australopithecus afarensis, which is the species that “Lucy” is part of. Previously it was thought that Lucy’s species evolved from A anamensis, but this find suggests that they evolved during the same era.

Sophisticated Neanderthals

Neanderthals were more sophisticated than we thought. We’ve slowly been learning more about Neanderthal culture and chipping away at the initial belief that were not very intelligent. It has already been found that they took care of their ill and injured, used complex tools, and buried their dead. This November, it was also determined that they used symbolic representations – they made art.

A Spanish research team was doing work in a cave in Calafell, Spain, studying the talons of imperial eagles. The talons had marks on them, and since eagle feet don’t really have much in the way of meat on them, the team concluded that the Neanderthals must have been wearing them as jewelry. It marked the first evidence that Iberian Neanderthals used personal ornaments.

Related Article: What a Year for History! The 8 Biggest Events that made 2019 Amazing

Each one of these discoveries has its role to play in helping to flesh out the complexities of human evolution and how we developed into who we are. Who knows how much more we may learn next year?