A tiny ‘mechanical’ insect once helped experts get their brains into gear… quite literally! While the natural and mechanical worlds seem poles apart, the ‘Issus coleoptratus’, commonly referred to as a nymph bug, showed they’re actually closely linked.

In 2013 this little creature – a ‘planthopper’ commonly seen in Europe and North Africa, which measures up to 0.28 ins – was discovered to house an astonishing organic propulsion system. A report published in Science reveals the Issus’ skeleton had gears in its hind legs.

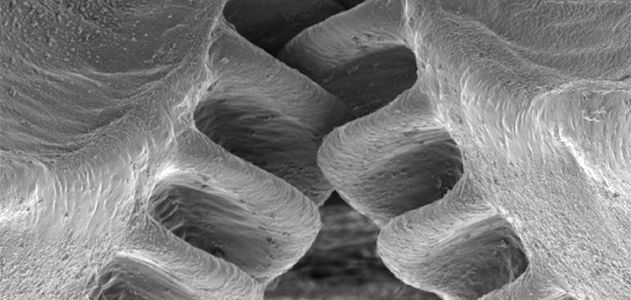

Authors and biologists Malcolm Burrows and Gregory Sutton observed “hind-leg joints with curved cog-like strips of opposing ‘teeth’ that intermesh, rotating like mechanical gears to synchronise the animal’s legs when it launches into a jump”, as described in their press release on EurekAlert. Their findings illustrate the “first observation of mechanical gearing in a biological structure.”

This would certainly have been news to the Greek mechanics of Alexandria, who are believed to have invented the mechanical gear in approx. 300 B.C.E. Turns out Mother Nature had them licked from the get go.

Burrows and Sutton used a combination of high speed video and experiments with dead Issus to reach this conclusion. The video gave them a precise look at the insects in action. Meanwhile, electrical stimulation of a single leg made it extend, hence triggering the other leg and showing the gears working together.

The release states that the insect’s inner-workings “bear remarkable engineering resemblance to those found on every bicycle and inside every car gear-box.” And that’s not all, because the design is also pretty sophisticated. “Each gear tooth has a rounded corner at the point it connects to the gear strip; a feature identical to man-made gears such as bike gears – essentially a shock-absorbing mechanism to stop teeth from shearing off.”

Issus coleoptratus not only relies on its gears to hop from plant to plant. It needs the mechanism to keep on the right track. “To jump, both of the insect’s hind legs must push forward at the exact same time,” explains Smithsonian.com. “Because they both swing laterally, if one were extended a fraction of a second earlier than the other, it’d push the insect off course to the right or left, instead of jumping straight forward.” This makes the little bug a perfect jumping machine.

The breakdown reads almost like an engine manual: “Each gear strip in the juvenile Issus was around 400 micrometres long and had between 10 to 12 teeth,” says the press release, “with both sides of the gear in each leg containing the same number – giving a gearing ratio of 1:1.”

However there are ways in which the insect differs from a straightforward machine. “Unlike man-made gears, each gear tooth is asymmetrical and curved towards the point where the cogs interlock – as man-made gears need a symmetric shape to work in both rotational directions, whereas the Issus gears are only powering one way to launch the animal forward.”

One puzzling feature is that the gears are only present in the juvenile/nymph stage. Once the Issus develops fully, it replaces the old system with what Science refers to as a “high-performance friction-based mechanism”. It’s thought as the insect reaches adulthood, it isn’t able to grow back any broken gears due to the molting process.

This is “when animals cast off rigid skin at key points in their development in order to grow”. Molting repairs any damage, so once the process stops a more durable solution is supplied by nature.

Related Article: Incredibly Intricate Gold Bug with Mechanical Wings Carved onto Silver Dollars

Having what amounts to a built-in machine isn’t exclusive to the Issus. A cog wheel turtle, for instance, is named after the cog visible on its shell. Yet this doesn’t serve any practical purpose, aside from looking decorative. Speculation on exactly how the ancient animal kingdom was powered will no doubt continue.

In the meantime, the Issus is a brilliant example of how mechanics are about blood and guts, as much as oil and grease.