An observatory in Chile is to be named after famed astronomer Vera Rubin. The news was announced in Honolulu, at an American Astronomical Society (AAS) meeting. Also involved on the funding side are the National Science Foundation and the Department of Energy.

Rubin, who passed away at Christmas 2016, battled to become part of the scientific community. Inspired by 19th century astronomer Maria Mitchell, she went on to establish evidence of dark matter in 1970. The observatory was formerly called the LSST (Large Synoptic Survey) telescope. It will now be called the Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

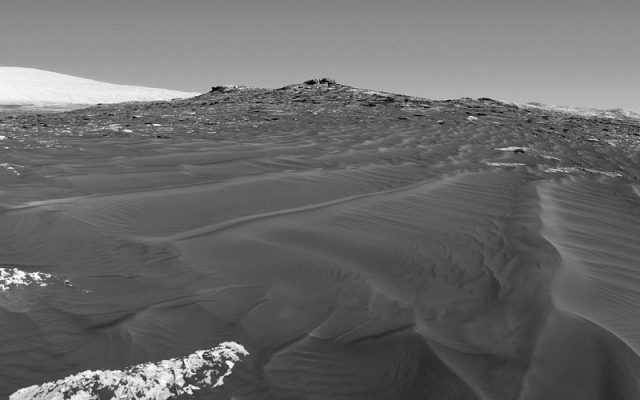

The venue is set to start stargazing in 2022, where it will spend 10 years surveying the heavens. Situated on the Cerro Pachón mountain ridge, it’s equipped with an 8.4 m telescope and 3200-megapixel camera.

The change followed months of effort by Congresswoman Jenniffer González-Colón and Chairwoman Eddie Bernice Johnson. Their co-sponsored bill sought to immortalize Rubin’s name so her legacy would never be forgotten.

Quoted by the AAS last July, Rep. González-Colón said, “Dr. Vera Rubin exemplifies the remarkable contributions women have long made to science. She persevered despite gender-based discrimination and challenges, and is recognized as a groundbreaking scientist in the field of astronomy.”

The re-titling is given extra poignancy due to another historic fact – in 1965, Rubin was the first woman to be granted official permission to observe at the Palomar Observatory in California. Now they’re naming them after her!

Her name is particularly associated with dark matter. The invisible yet vital element was first suggested by Fritz Zwicky in 1933. Rubin expanded the research, working with Kent Ford. “Her most consequential realization was that galaxies rotate so quickly that they ought to fly apart,” writes Space.com. “The fact that they don’t, she reasoned, is proof that there is a massive amount of, well, something in the universe that humans cannot yet study directly — what we now call dark matter.”

While they were building on ideas that had already been mooted, Rubin and Ford went out and bagged the compelling data. Smithsonian.com says she “offered some of the first evidence of dark matter’s existence, and her work flipped conventional views of the cosmos on their heads.”

Many feel her pioneering research hasn’t been afforded the proper credit. Despite talk of Rubin receiving the Nobel Prize for Physics, the actual honor never materialized. “Rubin spent her career measuring the forces of the universe she could not see,” notes Smithsonian. “But her reach included a far more visible change as well: her fight for gender parity in the sciences.”

Speaking about Rubin at the AAS meeting was Kathy Turner from the Department of Energy. Space.com reports her saying, “She (Rubin) has multiple legacies of, of course, the major science work, the major discoveries and the major legacy of paving way for young people and especially women.” Turner adds, “Her dogged determination to be recognized for her work was really something that stood out to me when I read more detail about her.”

Rubin certainly encountered strong opposition. Even her high school teacher is said to have discouraged her from a scientific path! She graduated as her class’s only astronomy major at Vassar as a teenager, before heading to Cornell. Harvard wanted her but she opted for Cornell as that’s where husband Bob was studying.

In 1950, following completion of her master’s thesis, she presented a talk at the AAS. “It solicited replies from several ‘angry-sounding men’,” Symmetry Magazine writes, quoting Rubin’s own words. Ironically its latest gathering enthusiastically puts her centre stage.

With a lot of support from her family, she took night classes for an astronomy PhD. From there she taught at Georgetown for 10 years. Her growing reputation led to this greatly-deserved current status.

Related Article: How a Felt Tip Pen Saved the Apollo 11 Crew from Being Stranded on the Moon

Another influential figure on Rubin was astrophysicist Margaret Burbidge, to whom she wrote the following: “From you we have learned that a woman too can rise to great heights as an astronomer, and that it’s all right to be charming, gracious, brilliant, and to be concerned for others as we make our way in the world of science.”

With much perseverance from both her and those she inspired, Vera Rubin’s name is written in lights… or at least, under them.

CORRECTION: In an earlier version of this article we mistakenly stated that this is the first time an observatory has been named for a woman. That is not accurate. We made the correction on 1/13/2020.