From hot dogs to tinned peas, processed food color is everywhere. No-one would claim manufactured products are natural, but when it comes to color people are accustomed to certain things. Some foods don’t feel right unless they’re bright red or green, even if that isn’t how they’re supposed to look.

Processed food has its origins in the early 19th century. Coloring however goes back a lot further. The FDA (US Food & Drug Administration) website mentions “Naturally occurring color additives” being used in ancient times. “Wine was artificially colored beginning in at least 300 BC” it notes.

The way consumables got their color is a complex and sometimes confrontational mix of producers, customers and of course the government. How does it all work? A good case study is margarine. The tasty spread has a surprisingly turbulent backstory, much of it involving appearances.

It should technically be white. Instead margarine is yellow. That’s to do with its status as a cheap butter substitute. Created in France 1869 as an economical alternative, it arrived in America 4 years later, though the dairy industry was worried. To enable a more level playing field, the color was altered to make margarine a less attractive proposition.

“By 1898, 26 states had regulated margarine under so-called ‘anti-color’ laws,” Smithsonian.com writes, “which prohibited the manufacture and sale of yellow-colored margarine (uncolored products were allowed).” Some of the developments sound pretty radical. The article goes on to say, “Vermont (1884), New Hampshire (1891), and South Dakota (1891) passed laws that required margarine to be colored pink.”

In the US there are the states, but then there’s the federal government. Higher powers introduced the Oleomargarine Act in 1886. All margarine would now be subject to a 2 cent tax for every pound. This legislation was amended in 1902, so colored margarine shouldered more of the burden. Talk about spreading the cost!

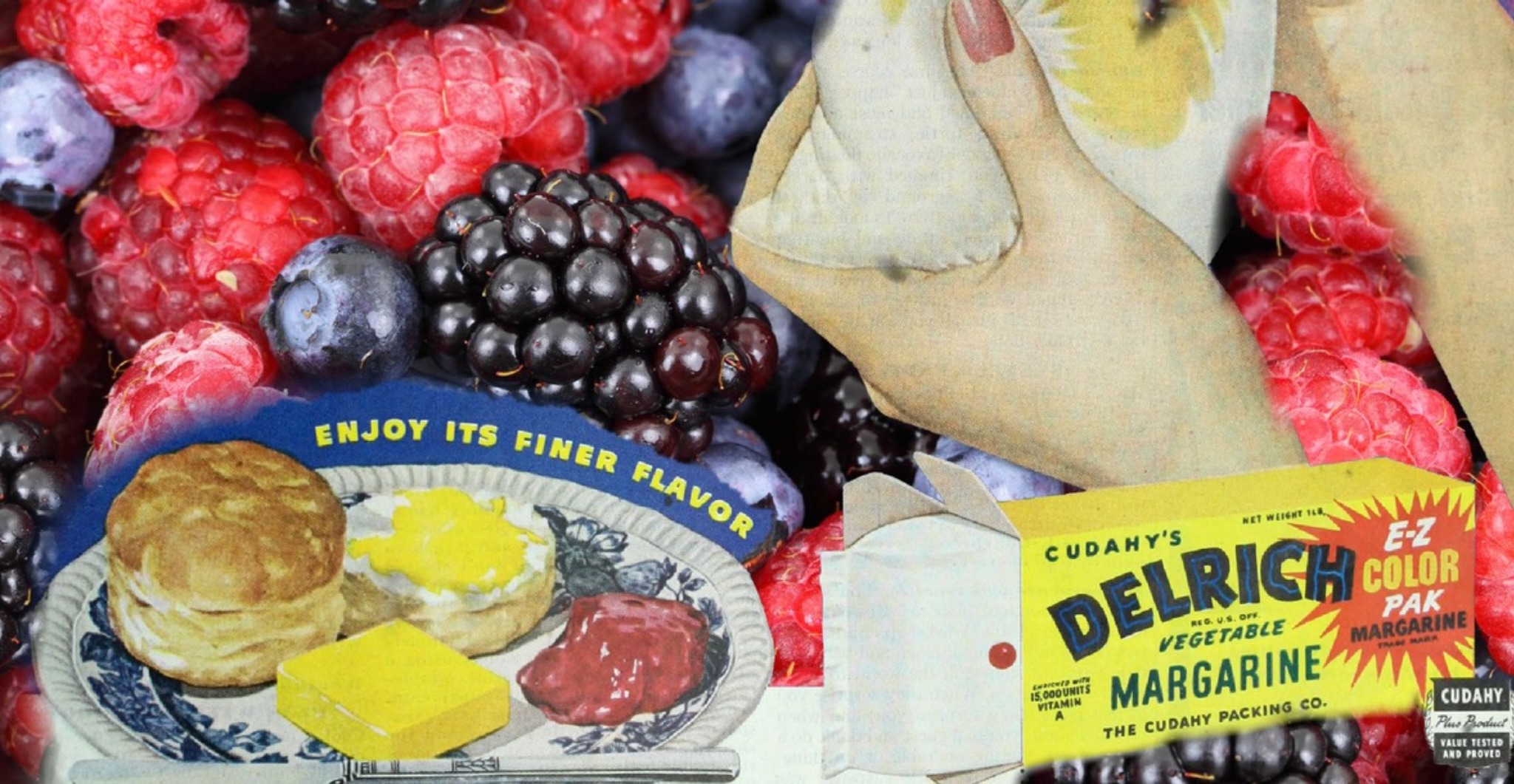

Manufacturers got around this red tape by having consumers do the mixing themselves. A vintage ad for Cudahy’s Delrich margarine from 1948 shows how a simple pinch of the bag can release yellow coloring into the white product. The idea was a capsule containing dye could be inserted separately at home. It was a crafty, if legitimate, practice that boosted sales by millions of dollars in the early 20th century.

Business battles aside, there are other practical reasons for regulating how food is colored. “A careful assessment of the chemicals used for coloring foods at the time found many blatantly poisonous materials,” the FDA writes, “such as lead, arsenic, and mercury being added.” This led to the 1906 Food & Drugs Act being established.

It “prohibited the use of poisonous or deleterious colors in confectionery and the coloring or staining of food to conceal damage or inferiority.” The FDA, initially called the Food, Drug and Insecticide Administration, took responsibility for enforcing the Act in 1927. Further measures followed in 1938 (Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act), with Color Additive Amendments introduced in 1960. Children becoming sick from eating an orange Halloween candy brand proved a driving force behind the update.

Other rules include the Grade Standards. In relation to dairy they are described as “voluntary” and “providing a common language of trade” by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s website. Its language reflects the balancing act required of such laws. “Any action AMS (Agricultural Marketing Service) takes on U.S. grade standards will reflect the broad interest of individuals, industry, and federal, state, and local agencies” the site states.

Dairy products were amongst the first colored consumables to be looked at by the US government. However scrutiny was also applied to a range of foods, like canned goods. 1930 saw standards passed by Congress. “For the color of canned peas,” Smithsonian writes, “not more than 4 percent of the peas in a can could be spotted or discolored.”

As for fruit, apples are routinely assessed. Explaining today’s standards for “red varieties, 50 to 60 percent of the surface needs to be covered with ‘good shade of solid red’ in order to be categorized as ‘U.S. Extra Fancy’ (the exact percentage depends on the variety).”

A sweet treat may look good but danger waits beneath the hard shell. After the ban on discredited food additive Red Dye No.2 in 1976, M & Ms decided to ditch their red versions for a while. Smithsonian points out, “although it had not used Red Dye No. 2, the firm abandoned the red food coloring due to consumers’ ‘confusion and concern’ over the dye, which the company worried could give consumers a negative impression of the red color in general.”

Related Article: Bubblegum Broccoli – The Crazy McDonald’s Idea to Get Children to Eat Veggies

This story sums up the challenges inherent in food coloring. Perception can be as strong as fact, meaning a reassuring shade can turn bad in the public eye at the drop of a hat. Maybe one day margarine will go back to pink, and that is what people will expect to see on the their dinner tables in decades to come…!