A new interpretation of the most famous Viking runestone is being used now in the debate on climate change. Runestones are usually found in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, but some are as far away as Scotland, Germany, and the United States. According to Real Scandinavia, about seven thousand runestones have been found, and half are from the time of the Vikings between the third and fourth centuries until the early twelfth century. They were generally used to memorialize people, as signs along the road for travelers, and to note personal heroism.

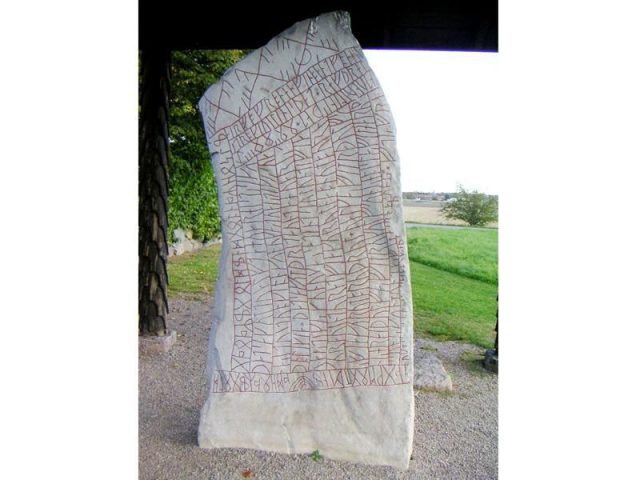

The stones could be taller than an adult or small enough to be placed on a table, and most still stand where they were placed but some have been moved to museums and other locations. The most famous runestone of all is the Rök Stone found at Östergötland in Sweden which is covered in seven hundred and thirty runes – more than any runestone found to date and the latest interpretation indicates that the message may be about climate problems.

The eight foot tall granite stone was erected by a man called Varin (or Varinn) in the early ninth century and still causes controversy today. Interpretations of the writings have been argued over since the stone was found in the wall of a twelfth century church during the nineteenth century.

The runes were at first believed to commemorate Varin’s dead son, Vämod, and his heroism as well as accounts of their family history, epic stories, and legends. The pagan god Thor is mentioned and Viking Archeology claims it may have been both a memorial and a status symbol for the family.

In 2016, another interpretation was presented by Per Holmberg, an associate professor of Scandinavian languages at the University of Gothenburg. According to Science Daily, Holmberg remarked, “The riddles on the front of the stone have to do with the daylight that we need to be able to read the runes, and on the back are riddles that probably have to do with the carving of the runes and the runic alphabet, the so called futhark.”

It was his belief that the stone was not simply a memorial to Vämod, but a description of how writing could be used to honor and remember the deceased. Holmberg has continued to lead studies on the Rök runestone and with the help of his associates, Bo Gräslund, professor in Archaeology at Uppsala University; Henrik Williams, professor in Scandinavian Languages with a specialty in Runology at Uppsala University, and Olof Sundqvist, professor in the History of Religions at Stockholm University, they have adapted Holmberg’s original theory.

According to an article from Smithsonian Magazine, the team has proposed that climatic events at the time of his carving led Varin to be concerned enough to document them. The new theory argues that the Rök Stone not only honored Varin’s son; it also commented on issues of climate that greatly impacted Viking survival.

This new translation of the Viking runestone is being used as evidence of a harbinger for climate change as it relates to the modern debate. The stone may refer to events in the sixth century when a series of volcanic events caused severe cold snaps, crop failures, starvation, and mass extinctions.

Varin may have been warning of a similar cataclysm; in the late eighth and early ninth century, the Vikings experienced a solar eclipse, a solar storm, and a cold summer. Weather catastrophes were also part of the warning signs of Ragnarök, leading to the end of the world.

According to an article from the University of Gothenburg, Per Holmberg’s multi-disciplinary team identified nine riddles on the Rök Stone, five in regard to the Sun and four about Odin, the principle Old Norse god and father of Thor. The Viking leaders saw themselves as able to control the light and the dark and would be soldiers of Odin in the eventual struggle for the light.

Related Article: Vikings in Minnesota? The Mystery of the Kensington Runestone

The stone’s inscriptions have distinct parallels with Old Norse stories to that effect. Much of the Rök Stone’s inscriptions are still not understood; archaeologists, historians, and linguists will continue to study this treasure of runes, and it remains to be seen if new interpretations will emerge.

Whether or not this Viking runestone was indeed a harbinger of climate change we have yet to see.