Sounds from the voice of a mummy are finally heard again! The technology of 3-D printing has made things possible that we could never have imagined even 20 years ago. The most recent of those things is that it allowed scientists to recreate the voice of a 3,000 year old Egyptian mummy, according to a recent report in the Independent.

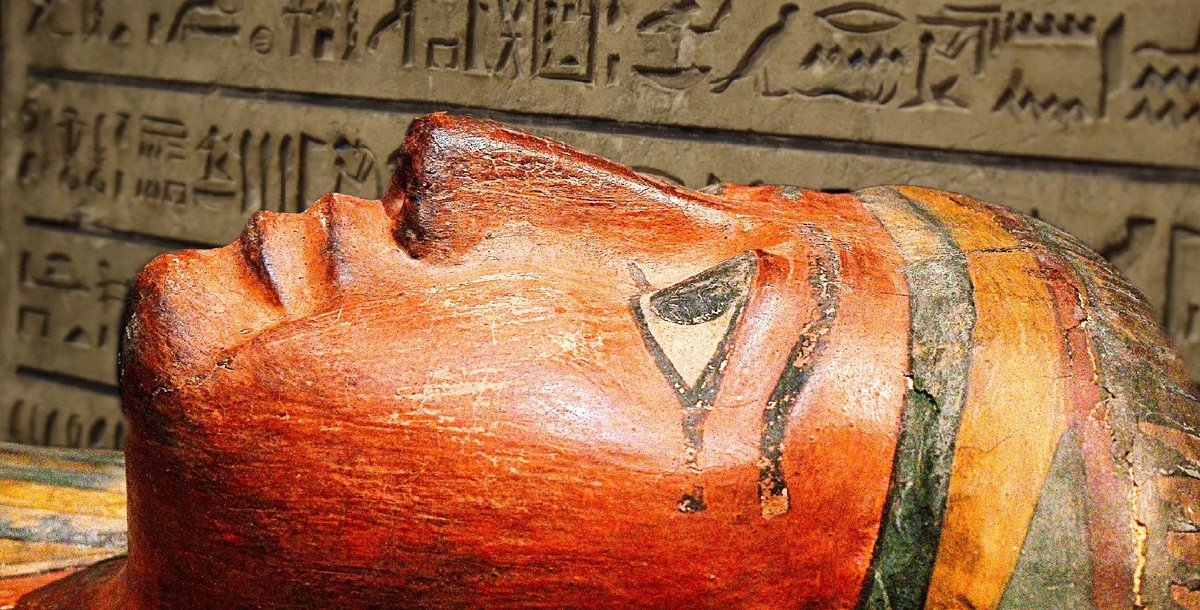

The mummy in question is that of the priest Nesyamun, and it is in a remarkably good state of preservation, which is what made everything possible. In most cases, remains as old as these are only bones, with all the soft tissue long gone, but Nesyamun’s mummy is an exception. The mummy retained enough soft tissue that scientists were able to artificially recreate his vocal tract, making it possible to get an idea of what his voice would have sounded like when he was alive.

The research and recreation were done by David Howard, a professor of engineering at the University of London, and three professors from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, Stephen Buckley, Joann Fletcher, and John Schofield, and took about five years to complete.

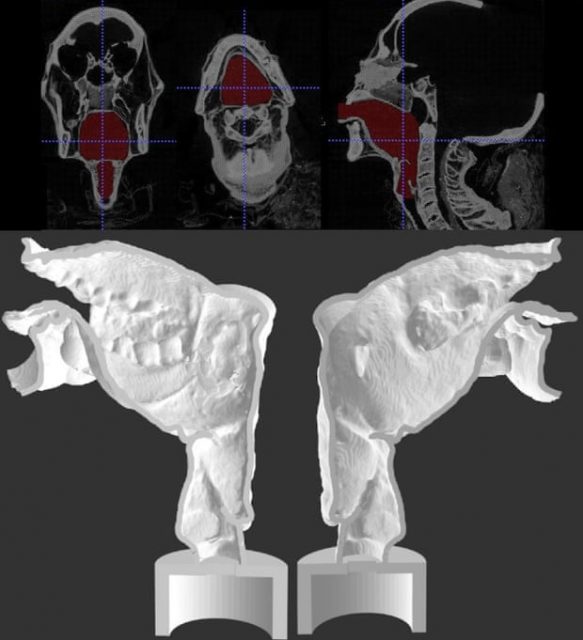

There still isn’t a way to recreate actual speech, but after 3-D printing the vocal tract, they were able to get it to produce a short, vowel-like sound that allowed an idea of how his voice would have sounded. The process involved using an array of technology, including using CT scans to get a detailed picture of his vocal tract for the printer to reproduce. It’s the specific dimensions and arrangement of the vocal tract, which runs from the larynx to the lips, that gives any individual their unique vocal quality, so having precise imaging was critically important to being able to re-create a faithful representation.

There has been some discussion about the ethics of work such as this, in that mummies and other ancient remains are often simply treated as artifacts, forgetting that they used to be people, but in this particular case it seems particularly fitting.

As a priest, Nesyamun’s voice would have been his primary tool for communicating both with his gods and with the worshipers through rites and rituals. His coffin even had inscriptions saying that in the afterlife, he wanted to be able to speak and move as he had while he was alive.

Furthermore, ancient Egyptians believed that to speak the name of the departed was to give hem life again. Now, in a way, he was able to speak again. Besides this research being rather in keeping with the priest’s own expressed wishes, none of the methods the team used for their research were destructive and were done with respect.

This is not the first time that 3-D printing has been used to try to learn more about what the ancients may have sounded like; in recent years, other teams of researchers used 3-D printing to create models of how the Neanderthal throat might have looked, to try to determine what Neanderthal voices would have sounded like.

In 2016, scientists in Italy did similar work with the remains of a man known as Otzi the Iceman, where they used CT scanning of his vocal tract to make a digital representation of what he might have sounded like. This is, however, the first time that the technology available has been used on the actual remains of a specific individual, allowing for a still-theoretical, but much closer to actual notion of how ancient people sounded.

Related Article: How to Make a Mummy? New Evidence on 5,600-yr-old Recipe Used for Embalming a Body

The priest’s mummy is in England, at the Leeds City Museum. He was first unwrapped in 1854, and it was determined that he was in his 50s when he passed. It’s very likely that the sound they recorded will be added to Nesyamun’s exhibit at the museum to give additional depth to the available knowledge about him, and to allow his voice to be heard in the afterlife, as it was in life, just as he wanted.