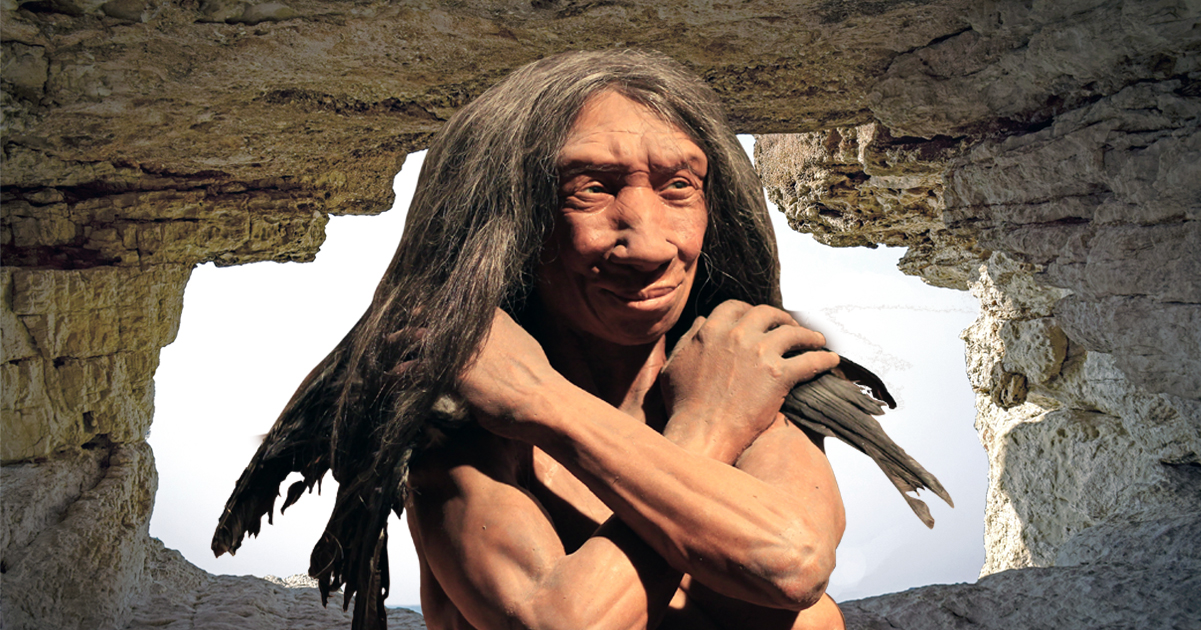

An incredible Neanderthal skeleton has been found at a site which has taught us plenty about Neanderthal burial practices. Archaeologists are not only concerned with how past cultures and civilizations lived, but how they ended as well. Much can be learned about a people by understanding the rituals surrounding the end of a life. These rites reveal a great deal about a culture’s level of sophistication, for example, and its religious beliefs can be inferred by how they were buried.

Understanding of Neanderthals has been advanced by discoveries made at Shanidar Cave, an archaeological excavation site in Iraqi Kurdistan. In the 1950s and 1960s, according to Cambridge Core, remains of skeletons of men, women, and children were found that provided a treasure trove of research possibilities regarding Neanderthal diet, appearance, and especially burial practices.

One skeleton in particular, labeled Shanidar 4, became well-known as the “Flower Burial” because bones were discovered with pollen clinging to the earth around the skeleton. The bones were identified as those of a 30 – 45 year old male, and the find led some scientists to conclude that Neanderthals may have been more refined in their burial rituals than previously thought. If they were burying their people with flowers, the thinking went, that indicated a certain sophistication not previously known.

Another theory, however, was that the pollen was simply placed in the earth by animals, and that it said nothing meaningful about Neanderthals whatsoever. For years, these opposing schools of thought had their detractors and supporters, but no new evidence proved absolutely either theory.

Recently, however, the discovery of a previously unexamined skeleton at Shanidar Cave has dazzled the archaeological world, and experts say much will be revealed by the bones, dubbed Shanidar Z. New, modern technologies will allow experts to learn more about Neanderthal burial practices that were previously unknown, according to Emma Pomeroy, an archaeologist at Cambridge University in the U.K.

She recently said, in an interview with ScienceAlert, that improved archeological equipment and techniques will provide better access to information about many things including DNA information to further explore Neanderthal evolution and relationship to modern humans. She believes that this find will provide more answers to the long-standing debate about Neanderthal burial practices and rituals – if they had rituals, and if they were anything like modern humans.

Debate continues about whether Neanderthals lacked the cultural sophistication and awareness that would result in complex burial rituals, but that belief has been upended by these discoveries at Shanidar Cave. The remains of Shanidar Z, in preliminary tests, have been dated as 70,000 years old.

It was found unexpectedly when a team of researchers from Cambridge, Birkbeck, and Liverpool John Moores universities, working with the Directorate of Antiquities for Soran Province and the Kurdistan General Directorate of Antiquities, went to collect more sediment from the Shanidar site, continuing studies on the original find, according to EurekAlert!. Shanidar Z was found buried in a very different position than others at the site, including one resting close to it.

This, Pomeroy explained, indicated that they were consciously placed in the grave in a very specific and deliberate way, not merely “dumped in” when the individuals expired. She notes that findings of cave markings, raptor talons, and shells may indicate that Neanderthals were, in fact, more culturally developed than previously assumed. It appears that burial rituals existed and changed over time as the people became more sophisticated.

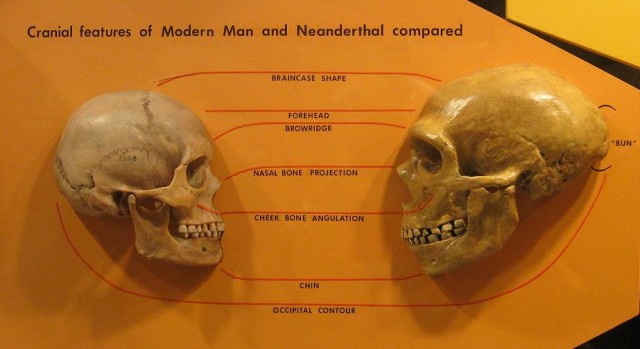

The site had been unavailable for several years because of conflict in the area, but scientists now have unfettered access to it, thanks to cooperation from the local Kurdish government. The bones are, at the moment, at Cambridge, where archaeologists and other experts are continuing tests which will determine everything from skull shape to whether Neanderthals bred with other hominins in the area.

Much remains to be learned from the Neanderthal skeleton, Pomeroy said. But she was certain of one factor – our ancient relatives were likely not the rough, unthinking species we often imagine they were. “If Neanderthals were using Shanidar Cave as a site of memory for the repeated ritual interment of their dead,” she proposed, “it would suggest cultural complexity of a high order.”

DNA Study: We may be More Neanderthal than Previously Thought

And that may mean that our ancestors, who lived so many thousands of centuries ago, were already on the path toward developing complex, respectful ways of burying their deceased just like we do today, no matter what religion we subscribe to or the culture to which we belong.