In today’s world, we take the idea of having extremely powerful computers not only accessible to us, but literally in our pockets. We use them to shop, play games, and look at memes, forgetting that this is far from their original conception. It’s also easy to forget that this is a relatively recent development, although it really is. Most Americans have more powerful computers in their cell phones then NASA used to land a man on the moon, which is where Katherine Johnson comes in.

In the middle of the last century, space exploration was becoming an imperative, but getting there took enormous amounts of careful calculation – mistakes could create incalculable losses in terms of both equipment and the lives of the astronauts on the ships.

People were needed who could meticulously make those calculations, and among them were a few highly-disciplined and mathematically gifted African-American women, including Katherine Johnson. It was the Jim Crow era, and not only were Johnson and her colleagues separated from the men who worked at NASA, they were also segregated from the white women, as well, with separate offices, bathrooms, and dining areas, according to the New York Times.

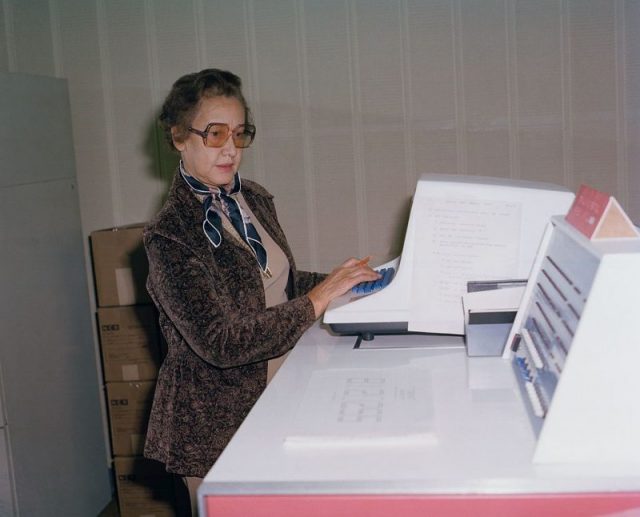

Although largely invisible to the public, Johnson’s contributions played a central role in the development of the space program. She and colleagues didn’t use supercomputers, they did their work the hard way; instead, they used graph paper, slider rules, and calculating machines and worked out their numbers on their own. Eventually, the caliber of their work earned them a certain amount of acceptance that transcended the fact that they were black.

One of Johnson’s tasks was to determine what trajectory the Mercury space capsule would need in order to re-enter Earth’s atmosphere, according to the Washington Post. The course was fist worked out by one of the computers of the day, but John Glenn insisted that they be confirmed using manual calculations, and the only person whose work he completely trusted for the job was Johnson’s. The risks for Glenn were high if things went wrong.

NASA wanted the capsule to land in a specific part of the ocean. If the capsule hit land, Glenn wouldn’t survive the impact. If the angle was wrong, the capsule would just bounce off the planet’s atmosphere. Glenn’s faith in Johnson’s confirmation of the trajectory was what ultimately allowed the launch to happen, as he had already cancelled it several times over worries of equipment failures and other problems.

Her work was proven when the Mercury capsule landed right where it was supposed to, after Glenn completed his orbit of the Earth. She was also responsible for calculating the trajectories that enabled the Apollo 11 to land both on the moon, and back on Earth once Neil Armstrong’s mission was complete.

By 1935, the agency that would eventually become NASA began hiring white women who were good at math, with the idea that having them crunching the numbers would save the male engineers from the tedium of needing to do it themselves.

Over the next ten years, those women were doing highly complex and necessary work, while being treated as sub-professionals and receiving substantially lower pay than their male counterparts. It wasn’t until after FDR signed Executive Order 8802 banning discrimination in the defense industry in June 1941 that black women were considered for hire.

In 1952 she heard that Langley, one of NASA’s oldest field centers, was hiring black women as mathematicians, and she took a job in Langley’s West Area Computing Unit, a segregated office for black women, completing sheets of data of male engineers.

Two weeks after she began working at Langley, her services were borrowed by the Flight Research Division, helping to calculate the aerodynamics of airplanes. She quickly proved her skill, and stayed with that division for the rest of her tenure at NASA. When the emphasis began to shift to supporting the entry of Americans into space, Johnson was involved in much of the math for calculating trajectories, figuring out launch windows and landing trajectories. As exciting as she found her work, much of it was kept secret, sometimes even not even she knew what it was for.

Because of her fascination with aerospace matters, she was instrumental in making it possible for women to attend the previously all-male briefings, as well. Johnson loved her work, despite the fact that she often worked 16-hour days that exhausted her to the point that she once pulled over to the side of the road and fell asleep in her car. She’s said that she and the people she worked with were the pioneers of the space era, and she always woke up excited to go do her job.

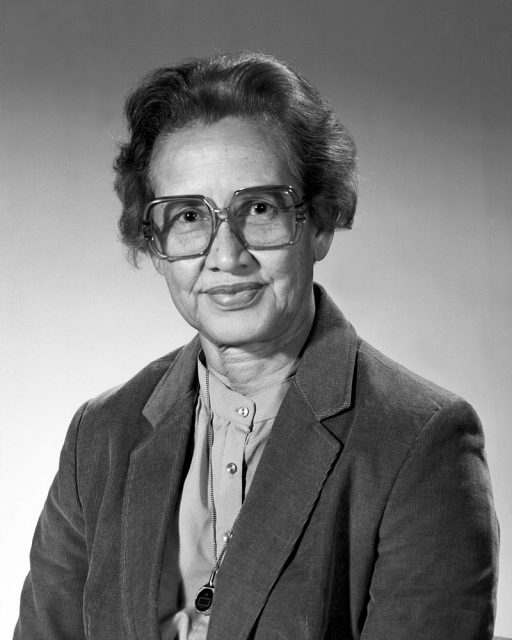

Johnson and the rest of the small group of African-American women who acted as ‘living computers’ for NASA were the central characters in the 2016 movie ‘Hidden Figures,’ although by the time of the film’s release, she was the only one among them who was still alive. She stood on stage with the cast of the film during the 2017 Academy Awards, an event at which ‘Hidden Figures’ received multiple nominations, including best picture.

Related Article: Observatory to be Named for Pioneering Female Astronomer Vera Rubin

If there’s one thing that her presence there absolutely did, it was to show young African-American girls that they, too, can literally shoot for the moon.

Katherine Johnson died this week at the age of 101, in a retirement home in Newport News, Virginia, leaving a lasting legacy in her impact on the space program, and in her role as an icon for female excellence.