This is the story of how one woman, Esther Pohl Lovejoy, in a time before women could vote, saved a city of over 200,000. Esther Clayton was born in what is now Washington State in 1869, and her family moved to Oregon soon after. Her upbringing was financially unstable, and she decided early on she did not want to be ordinary. When her little sister was born, Esther was impressed by the midwife who delivered her and decided she wanted to enter the field of medicine.

She entered the University of Oregon’s Medical School in 1894 and graduated at the top of her class after four years specializing in obstetrics and women’s health, according to Changing the Face of Medicine. After graduation, she married a fellow student, Emil Pohl, and they set up a private practice in Portland. During this time, she attended the West Side Postgraduate School in Chicago, and a few years later she and her husband moved to Alaska where her brothers were living.

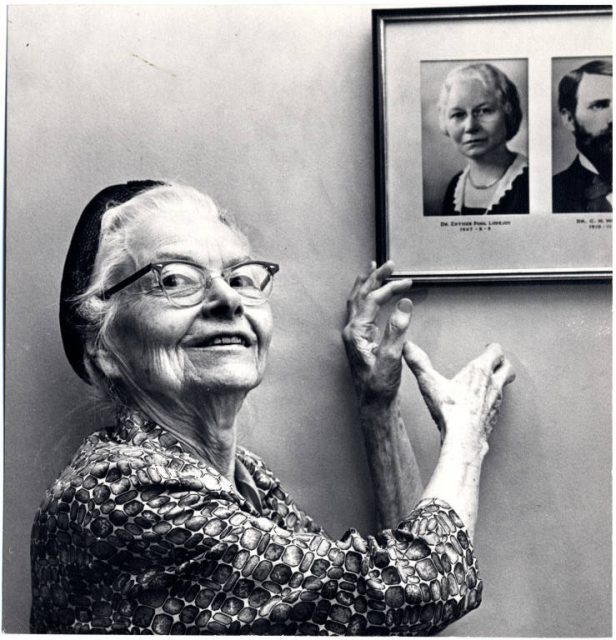

Two years later, Esther’s brother Frederick died, and she returned to Portland, spending summers in Alaska with her husband until he died in 1911. Esther went on to study in Vienna, Berlin, and Paris. She married Portland businessman George Lovejoy in 1912, but they divorced seven years later. During her lifetime, Esther helped with the establishment of the American Women’s Hospitals, wrote several medical books, directed the Portland Board of Health, helped found the Medical Women’s International Association, and provided Portland with the reputation of being one of the cleanest cities in America.

After the ravages of the Bubonic Plague in the 1300s, everyone thought it was defeated. In fact, according to the Center for Disease Control, it is still around today, but the difference is that we know what causes it, how it is spread, and, most importantly, a vaccine has been developed to control the disease.

The Bubonic Plague was brought to America in 1900 by rat infested ships bringing goods from Asia. That was focused in San Francisco and ended in 1904. In 1907, the plague reared its head again on the west coast, and Esther Pohl Lovejoy almost single-handedly saved Portland, Oregon. Lovejoy was, according to Smithsonian Magazine, the first female health officer in the country.

Lovejoy knew that the plague was spread by fleas that came in on the rats from freight ships, and she began a campaign to clean up Oregon. Several plague related deaths had already happened in Hawaii and San Francisco, and Lovejoy knew that she had to impress upon the local population that the cause was not Asian people, a sadly popular racial belief of the time. She decided to invite the press to walk around the docks with her.

What she found was raw sewage, garbage rotting in the streets, discarded rusting appliances, and general unhealthy filth. When she brought these matters to the attention of the Board of Health, they supported her and turned the matter over to City Council. She advised the city leaders that rat exterminators had to be hired, garbage needed to be contained and covered, and food had to be protected. The city officials gave Lovejoy permission to request as much money as was needed to help her get things done.

At the time, it was common to blame the plague on Asians, including Oregon State bacteriologist Ralph Matson who, in 1907 stated, “If we cannot compel the Hindu, Chinamen and others to live up to our ideals of cleanliness and if they persist in congregating in hovels and hoarding together like animals … the strictest kind of exclusion would not be too severe a remedy.” That is, in fact, how San Francisco had handled the 1900 outbreak — setting a quarantine on Chinatown and attempting to keep the news from spreading.

Lovejoy would have none of that and stressed the importance of cleaning up the docks. She enlisted the help of Aaron Zaik, an exterminator who had experience catching rats in New York and Seattle. He did such a great job that Lovejoy made him part of the health board. To further the success, Lovejoy put a bounty on rats at five cents per rat and instructed the public on how to properly handle them so as not to spread their fleas so they could bring them to the city crematory.

Related Article: The True Intent and Lady Behind the Famous Poem Etched on the Statue of Liberty

By the end of 1907, the plague had again disappeared from the west coast. Portland was the only west coast city that had no cases, and, according to Merilee Karr from the Portland Monthly, “There has still never been a case of Bubonic Plague within 100 miles of Portland.”