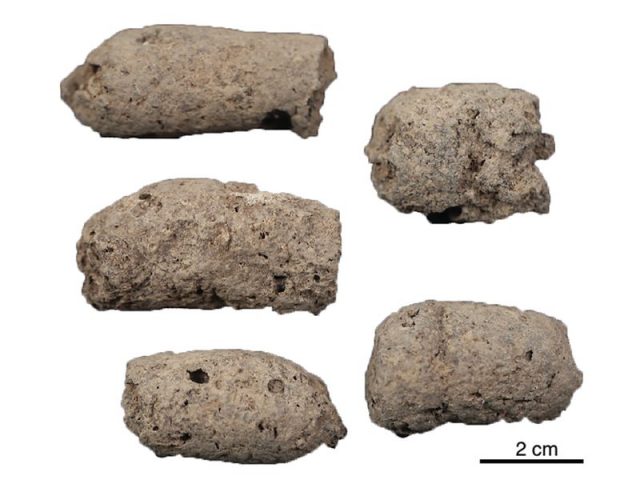

Ancient poop is telling scientists all sorts of things. Modern science uses all sorts of methods to learn about our distant past, and tries to leave no stone unturned. Useful information can come from even the unlikeliest sources – like coprolite. Coprolite is a fancy term for fossilized feces. As unglamorous as it is, it can still tell researchers about how people lived and what they ate thousands of years ago.

The drawback is that, as a famous children’s book says in its title, everybody poops. When archaeologists are doing work in areas where humans and dogs lived together, finding coprolite can be useful, but it can be tough to tell whose poop is whose after it’s been around long enough to fossilize.

Smithsonian magazine just reported on a new study that was published in the journal PeerJ which has the ability to remove the mystery. A team of researchers has developed a program they’re calling corpoID which uses AI to distinguish between coprolite which comes from humans and that which comes from canines, using bits of DNA.

As previously mentioned, coprolite can tell researchers a lot about the diet and health of the creature who left it behind, and can potentially tell them even more if there’s enough DNA still present in the sample. If they’re working in an area where humans and canines coexisted, however, it gets trickier. There is plenty of evidence to suggest that humans in various times and places have eaten canine, and as any pet owner will tell you, canines have no problem with treating feces as a tasty snack. Because of those two facts, small amounts of DNA from either species can end up in the feces of the other.

Even so, there are still distinct differences between their feces, largely dictated by the differences in the microbes present in their guts. Because those microbes vary from species to species, they make it possible to help figure out the source of the fossilized coprolite.

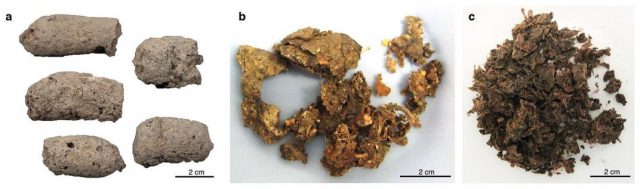

The scientists behind the recent research are a team from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, led by Maxime Borry. The team trained a computer to analyze and identify the DNA in fossilized poop and then compare it to samples of from humans and canines. Once the AI had been sufficiently trained, the team tested it out by having it analyze 20 different samples whose origins were either known or were strongly suspected. Seven of those samples only contained sediments.

The seven that only had sediments were identified as ‘uncertain’, as they expected. Seven of the remaining samples were correctly identified with regard to whether they were canine or human, but the six remaining samples proved to be a challenge. Borry’s team believes that those samples the computer couldn’t identify were problematic because the microbes in the DNA was atypical of what would be expected for either the canine or human samples they used to train the AI.

They could, for example, have come from a human who had recently consumed a lot of dog meat, or they could have come from dogs who ate a diet that was different enough from both modern dogs and their ancient brethren that it was reflected in the bacteria in their guts.

In an interview, Borry pointed out that not much is known about the microbiomes of ancient dogs, and it would be helpful to know more about how diverse the microbiomes of canines were in the distant reaches of history. Other scientists who were not involved in the research support that idea, pointing out that the samples the team used all came from dogs who lived in the Western world and in modern times, and that it was very possible there a lot more variation if you were to examine a more geographically diverse sample.

In addition to the mystery samples in the testing, the program was also unable to identify samples which were highly degraded and only had small amounts of DNA. The difficulties the program had are proof that more work needs to be done.

Related Article: The Largest Fossilized Human Turd Ever Found Came From a Sick Viking

However, if it continues to be developed and refined, corpoID also has the potential to give researchers a lot of new information about ancient people and their dogs, including when and how they started living together and how dogs changed when they began having less of the meat-heavy diet of their wild ancestors and instead started sharing the more diverse and starchy diets of their human companions.