The deadliest plague to ever spread was undoubtedly the Bubonic Plague, also known as the Black Death. It swept across the world in the first half of the 14th century, killing around 100 million people worldwide. Even though it didn’t go global until the medieval era, the plague is actually quite a bit older than that. For the most part, it’s believed that the plague first developed around China, approximately 2,000 years ago, but there has been some research suggesting it that the pathogen that causes the plague may have been present in Europe as early as 3,000 BC.

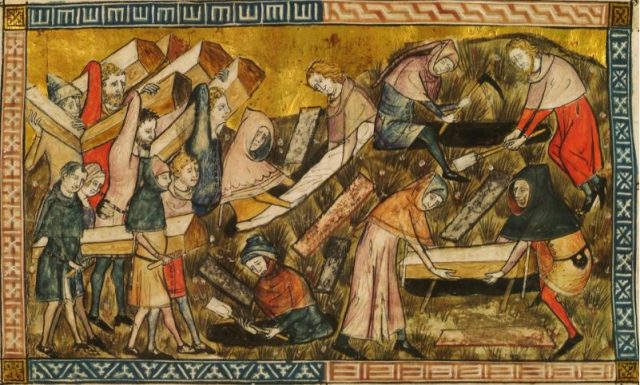

The plague hit Europe in October 1347, carried by 12 ships which had come from the Black Sea and docked in Messina, according to history.com. When the ships arrived, many of their crew were either dead or dying, and showing a truly gruesome array of symptoms. The most notable and obvious of those symptoms were eruptions of black boils on their bodies, which oozed pus and blood. The ships were ordered out of the harbor, but the damage was done. The first Europeans were infected, and the plague tore through Europe several times over the intervening years.

Before those ‘death ships’ reached Messina, the plague had already been decimating populations in China, Persia, Egypt, India, and Syria, spreading along the trade routes.

Part of what made the illness so terrifying is that no one had any solid explanations for how it spread, and no one really knew how to contain or treat it. In the modern era, bubonic plague can be cured with antibiotics, but no such thing existed in the medieval world. As a result, physicians tried treating the ailment with the tools they had on hand, using methods such as lancing the boils (buboes) and using poultices to draw out the infection, burning various herbs, and bloodletting.

Aside from the buboes, other symptoms were treated individually. Headaches were treated with sweet herbs such as bay, sage, rose, or lavender. Lung problems were treated with licorice or comfrey. Nausea was treated with mint. Unfortunately, none of the treatments used on sufferers actually addressed the root of the illness, itself.

The bubonic plague is a bacterial infection, specifically it is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis. It was transmitted to people through the bites of rats and fleas, and also becomes airborne. Both of those modes of transmission were devastating at the time. The standards for hygiene were very different in a world without indoor plumbing, and pests such as rats and fleas were endemic. Furthermore, people lived and worked packed together in cramped conditions, especially in cities.

Just like in the current pandemic, those who were able to practiced social distancing. If someone began to show symptoms, sometimes they would be abandoned by their families in hopes of avoiding the illness. Other times, if one person in a household showed symptoms, the house would be sealed with the residents kept inside until they either died or recovered. Shops closed, and people who were able to left the crowded cities and headed for the countryside, hoping to avoid the illness.

Heading for the country certainly helped, but it didn’t prove to be as effective as many would have liked, though. The plague could also be passed to animals, including sheep, chickens, cows, and other farm animals. The word ‘quarantine’ has its origin from this period. It started in Venice, where sailors would be required to stay on their ships for forty days to prove that they weren’t sick.

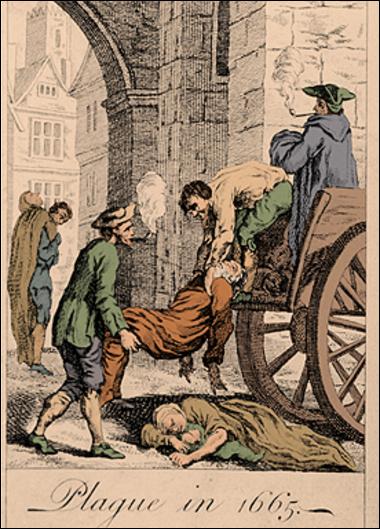

Even so, quarantining the sick, social distancing, and improvements in hygiene eventually caused the plague to retreat. It didn’t disappear entirely, however. Other outbreaks continued on and off for a number of years, although not to the same extent. Even after it seemed to have gone into retreat, the Black Death continued to show up every few decades for centuries.

Related Article: How one Woman Single-Handedly Saved Portland from the Plague in 1907

Thankfully, as history has progressed, so has sanitation and hygiene. Those improvements left the world better prepared to deal with the contagion. Interestingly enough, even though the plague can be treated and cured, the WHO still reports that there are between 1,000 and 3,000 new cases in the world annually, even now.