The Statue of Liberty is among the top 10 tourist draws in New York City. Boatloads of people take ferries out into the harbor to get a closer look of this famous statue, which has come to symbolize what is good about the United States. When “she” is lit up at night, it is as though the statue is extending its arm in a welcoming gesture, a greeting to all that they have reached a safe place.

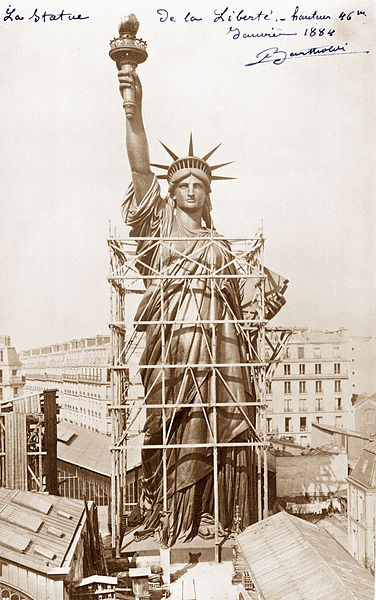

The statue was a gift to America from France, designed by famous sculptor Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, but the internal build, so to speak, the structure within that allows it to stand and extend that famous arm, was designed by architect Gustave Eiffel. Eiffel, as virtually everyone on the planet knows, gifted Paris with a similarly famous landmark, the Eiffel Tower.

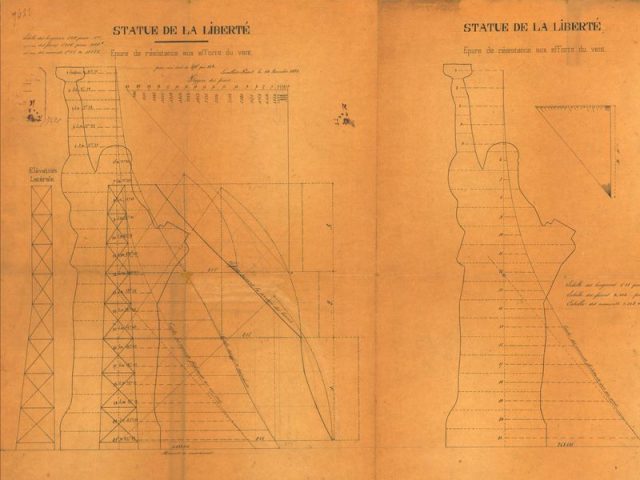

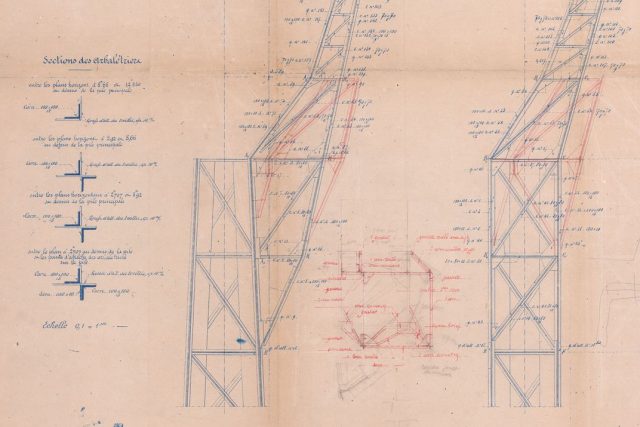

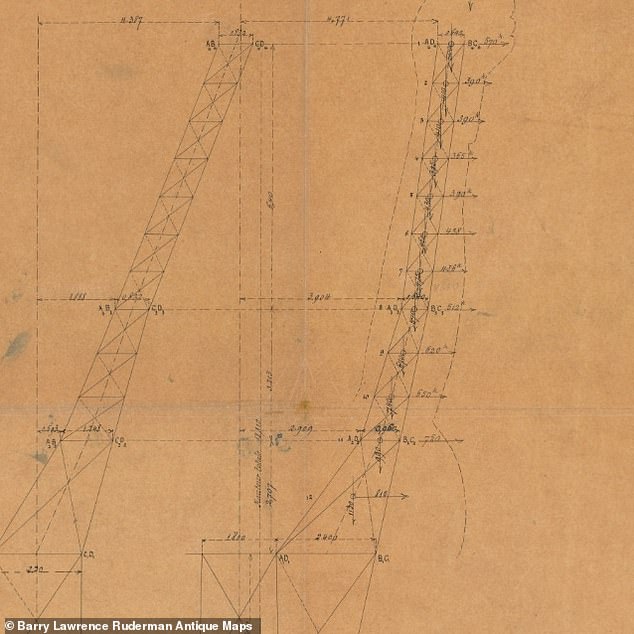

But as California-based map collector Barry Ruderman discovered in 2018, when he bought a briefcase filled with drawings from Eiffel’s office, the statue that was ultimately built was not exactly the one that was Eiffel designed. Ruderman found 22 technical and engineering drawings of the statue, with several notations in the margins by Eiffel, and members of his team.

No one knows for sure who changed Lady Liberty’s arm, but someone did, an engineer probably, one who worked on the project during the building phase. Originally, Eiffel wanted Liberty’s shoulder and arm to be more “bulked up,” because, as an architect and engineer who had experience designing bridges, he knew the arm needed strong supports within to withstand whatever nature flung at it. It also had to deal with salt water corrosion from waves, which presented an entirely different set of challenges.

Some experts suspect that the engineer who changed it did so with the tacit approval of Bartholdi. The alterations made Lady Liberty’s right arm more slender and sleek, but they also made it susceptible to the strong winds that thunder through the harbour frequently, then and now.

The statue was gifted to America in 1870, but wasn’t ready for display, and a formal dedication, until 1886. It symbolized the friendship between France and America, after the latter country’s revolution, which France supported. It stands 151 feet tall, and in its right hand is a torch, always lit at night, that adds symbolic strength and the notion that in essence, New York City never closes. The statue is coated in a thin copper, and sits on a huge concrete base.

Although it may have adhered more closely to the vision Bartholdi had, the trimmer arm meant that she wasn’t just at risk of damage from weather, but outside, unnatural forces too, like the saboteur who blew up a munitions warehouse close by, damaging the arm and torch. That happened in 1916, right in the middle of the First World War, and the statue symbolized negative things to America’s enemies at the time.

The blueprints Ruderman found, quite by surprise, are only the third set known by historians, who told Smithsonian Magazine recently that one set is in the Library of Congress, while a second set is in the collection of a private owner in France. Edward Berenson, a historian at New York University, told the magazine that the blueprints may represent “evidence for a change in the angle that we ended up with in the real Statue of Liberty. It looks like somebody (was) trying to figure out how to change the angle of the arm without wrecking the support.”

SEE: The Amazing Construction of the Statue of Liberty in Photos

Whether it was some anonymous engineer who took it upon himself to make the change, or whether he did it at the urging of the sculptor, experts can’t be sure. What they are sure of, what everyone is sure of, is that the Statue of Liberty represents the best parts of American society, the democratic principles on which the nation was founded. To some, those principles have come to mean freedom, safety, and strength, exactly what Lady Liberty herself was intended to convey.