Lost cities, settlements, structures and sites from Britain’s ancient past have been discovered in the most remarkable of circumstances. Understanding Landscapes, a project of the University of Exeter, was founded in 2017 to identify and record ancient sites in southwest England at Bere Ferrers, Calstock, the National Trust’s Cotehele estate, and Ipplepen. At the moment, no current archaeological digs are taking place as everyone is staying home, so they asked for eight volunteers working at home to look at aerial surveys between Cornwall and Devon, and professional archaeologists are stunned by the results.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the team is led by Dr. Christopher Smart, a post-doctoral research associate at Exeter whose specialty is Roman and medieval Britain. Smart remarked that the population in the area turns out to be much larger than they anticipated. The team expected to find sites like these, but the number of sites is a surprise.

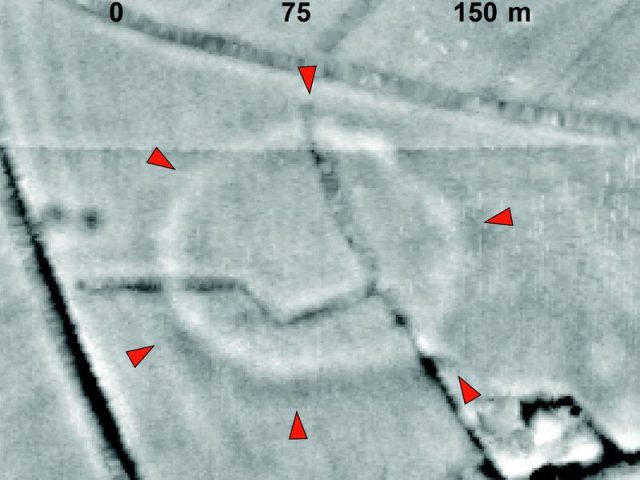

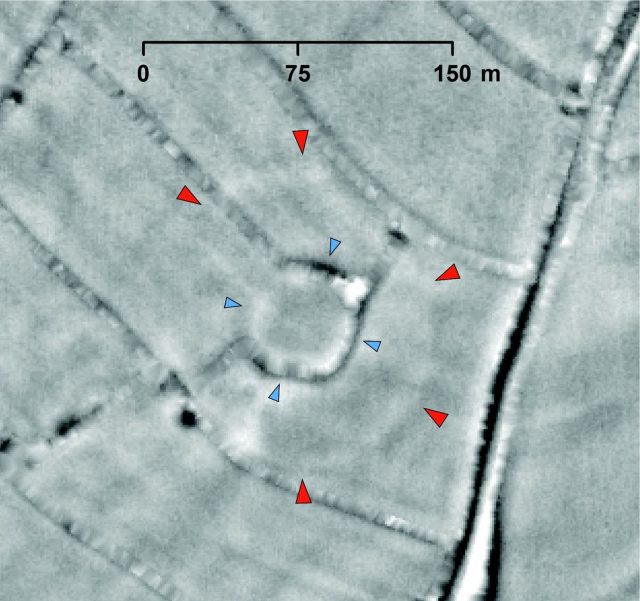

The volunteers are studying 3D scans of one thousand five hundred and forty-four square miles looking for roads and other manmade structures to cross-reference with already established archeological information. Each volunteer gets one thousand grids to examine. The grids have so far revealed thirty previously unknown lost cities and settlements dating from about 300 BC to 300 AD and many miles of Roman military roads that linked Calstock Fort near Tavistock to Restormel Fort near Bodmin. Dr. Smart, noted in The Guardian, expressed his frustration at not being able to excavate as they had planned to do this summer. He hopes that the interruption caused by the global health situation will pass quickly and that they will be in the field again soon.

With only about ten percent of the area analyzed so far, the team has found thirty either Roman or prehistoric settlements, twenty burial mounds, medieval farms, and quarries. Up until now, it appeared that the Romans went no farther than Exeter, but this new evidence may change that belief.

A Neolithic henge was spotted in photographs in south Derbyshire, but until the team is able to dig, nothing can be confidently confirmed. Lisa Westcott Wilkins, managing director of the archaeology company, DigVentures, believes it is most definitely something to be excited about. Earlier in Ipplepen, over one hundred Roman coins ranging from 49 BC to 408 AD have been unearthed showing the Roman economy reached farther than previously thought.

The roads were completed about 43 AD to 70 AD and show wheel ruts and a few potholes hinting that this area was well-traveled in Roman times. Roman amphora – large baked clay jugs used to ship olive oil, wine, and foodstuffs and imported Samian ware from the first and second centuries AD have also been found. The Samian ware originated in France demonstrating that some of the inhabitants were wealthy enough to have imported goods.

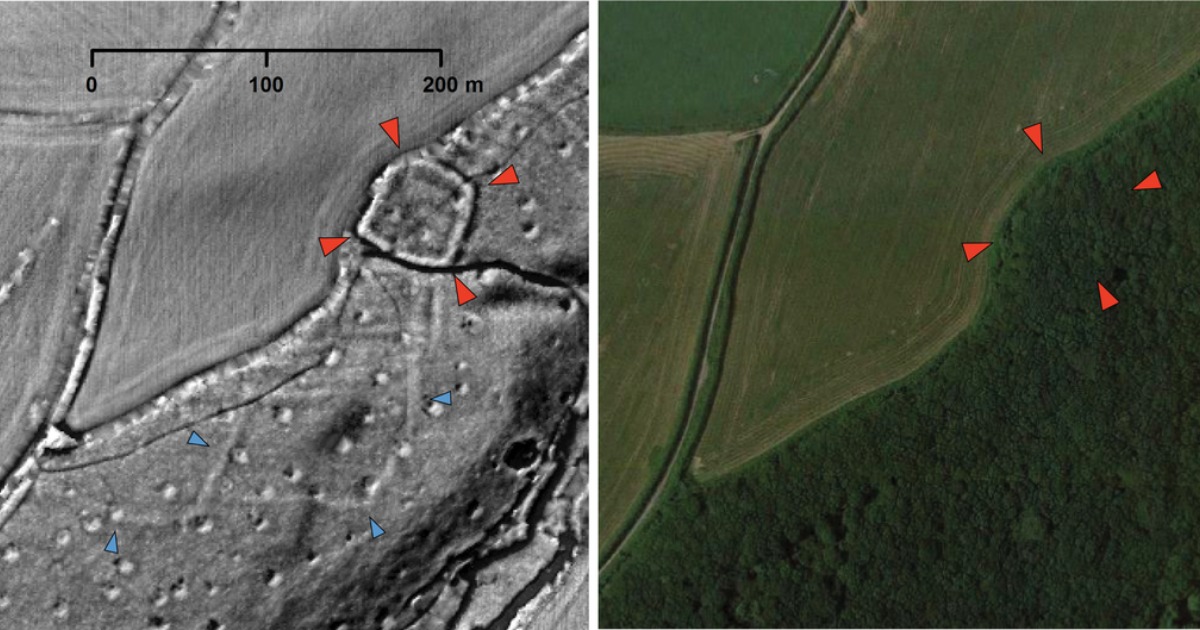

The photos are taken using laser light collected by a device called Lidar—Light Detecting and Ranging—connected to an airplane or helicopter. It uses a pulsed laser that measures variable distances to the Earth, according to NOAA. A scanner and GPS device also help to examine both natural and manmade surroundings with an accurate image of surface features.

There are two different types of Lidar; topographic is used mostly on land and bathymetric has the ability to penetrate water to measure lakes, rivers, and seafloor. It measures latitude, longitude, and height from the reflected laser pulses to determine any unusual features, almost like being able to see under the earth and oceans.

Related Article: Beautifully Preserved Iron Age Artifacts Found Under Norwegian Glaciers

With this type of equipment, not only can scientists find hidden features and lost cities, but they can also watch the progression of beach erosion, the rise of sea levels, forestry trends, fish habitats, losses in natural disasters such as earthquakes and floods, tide alerts, and changes in the ocean’s ecosystem. They can also continue to study ancient sites during a pandemic.