Twenty miles from Lyons, France, an Iron Age “princess” has been discovered while construction work was going on near Saint-Vulbas. In the course of excavation, workers found a 2,800-year-old burial site. The tomb belonged to a woman early in the Iron Age, from around the 8th century BC. Media sources have since dubbed her a princess because of the jewelry she was wearing when she was interred.

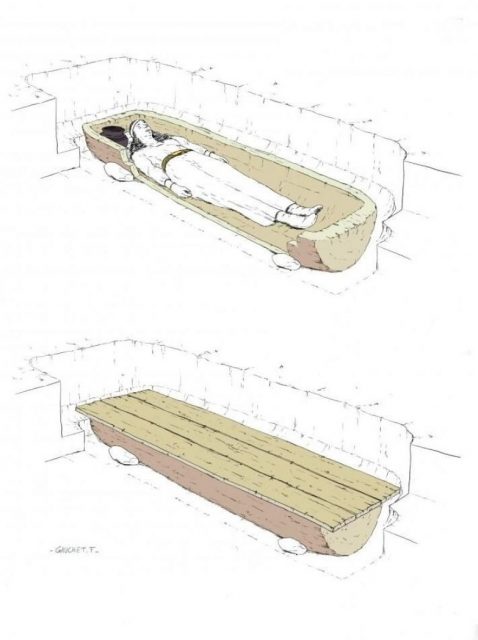

The woman was found resting in an oak coffin, with enough jewelry and high-status items that there’s little doubt she was from the upper crust, according to a report from Fox News. The tomb was roughly 8.5 feet by 3.5 feet, with rollers on the bottom that were positioned in a way that a wooden coffin could be wedged into the space. The coffin held the remains of the ‘princess.’ She was laid out on her back with her arms stretched out beside her, dressed, and wearing her jewelry.

On each of her wrists, she wore bracelets made ring-shaped beads of blue or blue-green glass, and decorated with threads of a lighter color. The glass beads were alternated with discoid beads made of a copper alloy. She wore a belt with a clip made from the same alloy. The belt itself was probably made of leather and has long since rotted away, but the copper buckle remains.

Given the technology of the time, the glass beads, in particular, would have been rare and hard to make, which is a sure sign of the woman’s wealth and status. Besides the jewelry already mentioned, her grave also contained stacks of small disks which were made from something which resembled pearls. The copper beads in the bracelets had long since developed a green patina during their centuries underground, as did the belt buckle. The buck not only had the same green patina as the beads, but is worn with time that it’s nearly impossible to make out the decorative designs on it.

Her tomb is one of three that were discovered that date from roughly the same period, according to the Daily Mail. The other two tombs were a bit more recent, dating from around the 5th century BC, and the remains they contained appeared to have been cremated. The other tombs were marked with a funerary monument with four posts, and were surrounded by a shallow moat.

The site was divided in half, with separate sets of remains in each half. One half held a limestone-lined wooden box that contained washed bone and the fragment of bracelets. In the other half, a mix of bones and charcoal from the funerary pyre were contained in a basket-like container. The bones were too degraded from being burned to examine them for clues about the person they belonged to, but copper bracelets and an iron belt clip suggest the remains belong to another woman.

All the tombs were uncovered when workers were removing soil from the area as part of the work to build an industrial park.

The occupants of the tombs were all members of the Hallstatt culture, an early Iron Age civilization that existed between 800 and 450 BC, and spread across Central Europe. As a whole, the culture was known for two things, agriculture and fine artifacts.

Related Article: Two Lucky Metal Detectorists Find Record-Breaking Iron Age Coin Hoard

The culture was made of independent tribes with no political ties, but who were connected through an extensive trading network, through which they exchanged everything from housewares to farming techniques. They are particularly known for trading metal such as tin, copper, and iron as far as the Mediterranean. Besides the discovery of the tombs, particularly that of the ‘princess,’ simply being interesting in their own right, the discoveries also allow researchers to gain insight into how funerary practices in one culture can shift over time as the culture itself evolves.