Benjamin the last Tasmanian tiger lives again in rare film footage! Approximately three mins of footage previously existed of this marsupial predator. This find adds a short but very sweet 21 seconds, and features the impressive creature moving around his enclosure. In line with recent archive presentations, Benjamin is rendered in glorious 4K.

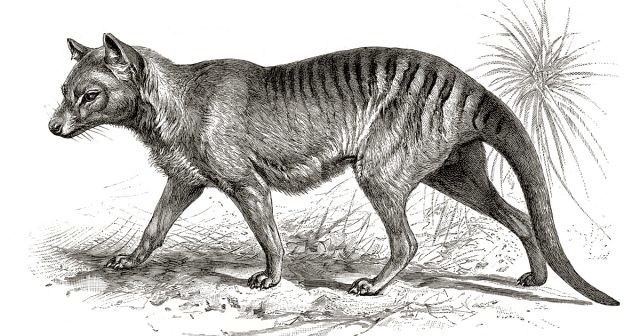

Kept in captivity at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Benjamin is the last known example of a thylacine (Tasmanian tiger). Referred to as a tiger owing to his stripy back, his distinctive presence was immortalized on celluloid 85 years ago. The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia (NFSA) released the “new” material. “These images had not been seen by the public in decades, until they were rediscovered and brought to our attention by researchers Branden Holmes, Gareth Linnard and Mike Williams, from the Tasmanian Tiger Archives” the organization said in a statement. “They located the vision within a forgotten travelogue, Tasmania the Wonderland (1935).”

This was filmed by Sidney Cook, described by NFSA as “an unsung pioneer of Australian filmmaking, who had worked in the Salvation Army’s Limelight Department.” The footage shows “Zookeeper Arthur Reid and an associate rattle his cage at the far right of frame, attempting to cajole some action or perhaps elicit one of the marsupial’s famous threat-yawns.”

Despite the fascinating scene, it’s believed Benjamin didn’t have a good time at Beaumaris Zoo. He’d been taken from the Florentine Valley and lived the rest of his days away from his natural habitat. “The long sad story of what was the world’s largest marsupial carnivore and it’s very public decline has haunted Australians” writes Australian Geographic.

What happened? Sadly, Benjamin was unable to access shelter one night during freezing conditions. Forced to lay on concrete, he developed a chill from which he never recovered. He died in 1936, the year after Cook filmed him. Strangely, the filmmaker himself passed away several months later. The National Museum of Australia states Benjamin died from “suspected neglect”.

With Benjamin went all traces of the thylacine. Since then, the animal has taken on an almost mythic status. The last Tasmanian tiger may have ended up in captivity but history tells a different story. “Thousands of years ago, the thylacine roamed across New Guinea and mainland Australia” writes Mongabay.

When European settlers arrived to make the continent their own, thylacines were thought to number 5,000. Many of the arrivals were farmers, who brought livestock into the area. When chunks were taken out of their income – quite literally, as things were being eaten! – attention turned to the tigers.

“Despite evidence that feral dogs and widespread mismanagement were responsible for the majority of stock losses,” the Museum says, “the thylacine became an easy scapegoat and was hated and feared by the Tasmanian public”. The majority of the prevalent predators were wiped out by hunting, diseases and loss of habitat.

By the 1920s they were in a sorry state and extinction wasn’t far away. A “Mr A.W. Burbury” is quoted from The Examiner (Launceston) in 1937 by the Museum. According to him, there was “no reliable evidence that the Tasmanian tiger was now in existence”. The Museum keeps the memory of the tigers alive, with a collection “including what is believed to be the only surviving complete ‘wet specimen’ (a biological specimen kept in preserving fluid). Other pieces include two thylacine pelts, skeleton, and more than 30 body parts that were preserved by the Australian Institute of Anatomy.”

Tragically the government had agreed to protect the species just 2 months before Benjamin’s demise. Yet is that really the end of the story? People think the Tasmanian tiger has vanished from the map… but not everyone. And maybe not all nature seekers are driven by scientific curiosity. For example, in 1984 famous tycoon Ted Turner offered a cool $100,000 for evidence of thylacines. There were other explorations, however a couple of years later the animal was officially declared dead as a dodo.

Then in 2016 a study revealed that Benjamin may not have been as alone in the world as he thought. Australian Geographic writes that “based on the thylacine’s range and sightings before 1936, they calculate 200–400 thylacines survived into the 1930s. Almost certainly, they suggest, based on the same factors and evidence reported by a number of reliable experts, some thylacines survived into the 1940s.”

Any speculation on the fate of the tigers has to be taken with a few pinches of Tasmanian salt. The site mentions “They do not claim any certainty beyond that point however… the notoriety of the thylacine’s story, their mostly nocturnal and shy nature and the fallacy of eyewitness accounts has meant that a question mark surrounds the time that thylacines died out.”

Find out more about the Sad Final Night at the Zoo of the World’s Last Tasmanian Tiger

Speaking to Mongabay, expert Nick Mooney thinks this fresh glimpse puts some flesh back on the bones of the missing marsupial. “It does give a bit more information on turning and pace in movement,” he comments, “which is both interesting and potentially useful for interpreting sighting reports and bits of video people claim might be thylacine”.

Maybe after so many decades within the confines of a black and white screen, Benjamin could help identify the remains of his civilization. While it’s feared by some that the tragedy could happen all over again, these precious seconds contain a slight glimmer of hope for fans of the “Tassie tiger”.