Ayers Rock is now a no go for Google. The indigenous Anangu people and Parks Australia have ruled the location off limits for virtual explorers.

ABC News reports that “360-degree images of the summit of Uluru” were available via the search engine giant. A stunning online diversion for some, but not for those who own it!

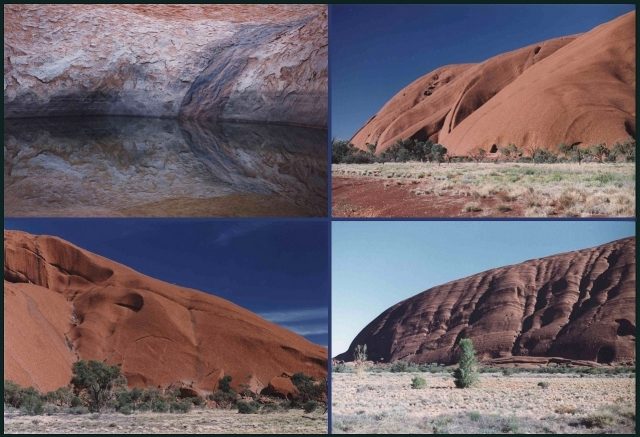

The Anangu follow ancient law that started with Tjukurpa, or period of creation. Alongside Kata Tjuta – previously Mount Olga – in the Northern Territory, Uluru is an ancestral homeland, with sacred links going back thousands of years.

Uluru was returned to them by authorities back in 1985. There then ensued a campaign to stop people climbing what’s also referred to as Ayers Rock. Late last year a ban on such activity was put in place. Reuters writes putting Uluru on Street View “effectively defies the ban”, together with Park Australia’s rules and regs on photography.

Speaking to ABC, Google reveal: “As soon as Parks Australia raised their concerns about this user contribution, we removed the imagery.” The process reportedly wasn’t immediate, with a time frame of approx 24 hours specified.

The area has been a national park since 1950. Up to that point the landmark and its surroundings were part of an Aboriginal reserve. The Parks Australia website describes it as “a living cultural landscape”. In 1993 it became Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park.

In terms of non-indigenous experience, Uluru was first documented by explorer William Gosse in 1873. “Ayers Rock” was a tribute to Chief Secretary of South Australia Sir Henry Ayers. Its prominence is 348 m, with a circumference of 9.4 km.

While the Anangu have owned the rock for several decades – managing it with Parks Australia and leasing land to the Australian government – it’s been a slow process for their concerns to be recognized. The prospect of a ban on scaling Uluru produced defiant results.

BBC News writes that “huge crowds gathered in the weeks before the ban, with some social-media users capturing lines of visitors queuing up to make the climb.”

As part of an article for The Independent, the sign at Uluru’s base is highlighted. Written by the Anangu, it reads the site is “sacred in our culture, a place of great knowledge. Under our traditional law, climbing is not permitted. This is our home. Please don’t climb.”

Long before the advent of Google, filmmakers visited the rock. 1988’s ‘Young Einstein’ is just one of the surprising big screen productions that used Uluru as a location.

‘The Man From Hong Kong’ (1975) also filmed there. A rare example of a kung fu flick produced Down Under, it was Brian Trenchard-Smith’s directorial debut. Smith became a well-known name in the genre of ‘Ozploitation’.

Action and comedy aside, Parks Australia are keen to mention the rich culture of the area. They write that visitors “may see people dot painting, performing inma (traditional dance and song), telling Tjukurpa stories or gathering bush tucker” they write.

Wildlife at Uluru includes 178 types of bird. Shrimps are among the more surprising inhabitants of this supposedly dry and dusty landscape. According to Parks Australia,

eggs from crustaceans – or “shield shrimps” – can lay there for years before spells of heavy rain provide the right conditions to hatch. They enjoy the brief appearance of rock pools before the sun comes out again.

While it may appear otherwise, the park sustains over 400 examples of plant life. These are used for medicine and even tools.

Another Article From Us: SS Cotopaxi Vanished in the Bermuda Triangle, Has Been Found 95 Years Later

Arguments about national heritage are happening all over the world. When it comes to Uluru, the matter appears to be settled. The titans of the tech world may set trends in the modern world. But this story shows there are still some higher powers out there than Google…!