Horror stories have always been a huge part of mankind’s collective nightmares. Evil creatures – including witches and werewolves, demons and vampires – comprise a component of many nations’ artistic output, in everything from plays to movies, novels to television shows.

We love to be terrified, it would seem, as the profits from movies like “Night of the Living Dead” and “Halloween,” (to which there are endless sequels) clearly testify.

Witches themselves take centre stage in creative endeavours like “The Crucible,” by Arthur Miller, a play about the Salem witch trials, and “Macbeth”, by Shakespeare. Yes, if it were not for our love of being scared silly, novelists like Stephen King would be out of a job.

For the past century, more or less, we’ve viewed horror in all its many forms largely through the lens of entertainment, or at the very least amusement. Few people believe in the supernatural anymore, and the ones who do keep those beliefs largely to themselves.

But only a few centuries ago mankind believed most ardently in witchcraft and all kinds of other supernatural expressions.

Think of all the people, largely women, who were burned at the stake during the Inquisition, including Joan of Arc, put to death in France in 1431. It was not until the 18th century, according to the Encyclopedia Britannia, that burning people – for any reason – was banned in England.

Thinking back on all those times when people were feared, for having different beliefs, different looks, or even just family feuds, it’s not surprising that folks took their efforts to ward off evil very seriously.

And those efforts included markings, often on doorways and roofs, that were expected to inhibit a ghoul’s intentions, rather like holding a cross up to a vampire keeps it at bay, as happens in Bram Stoker’s “Dracula.”

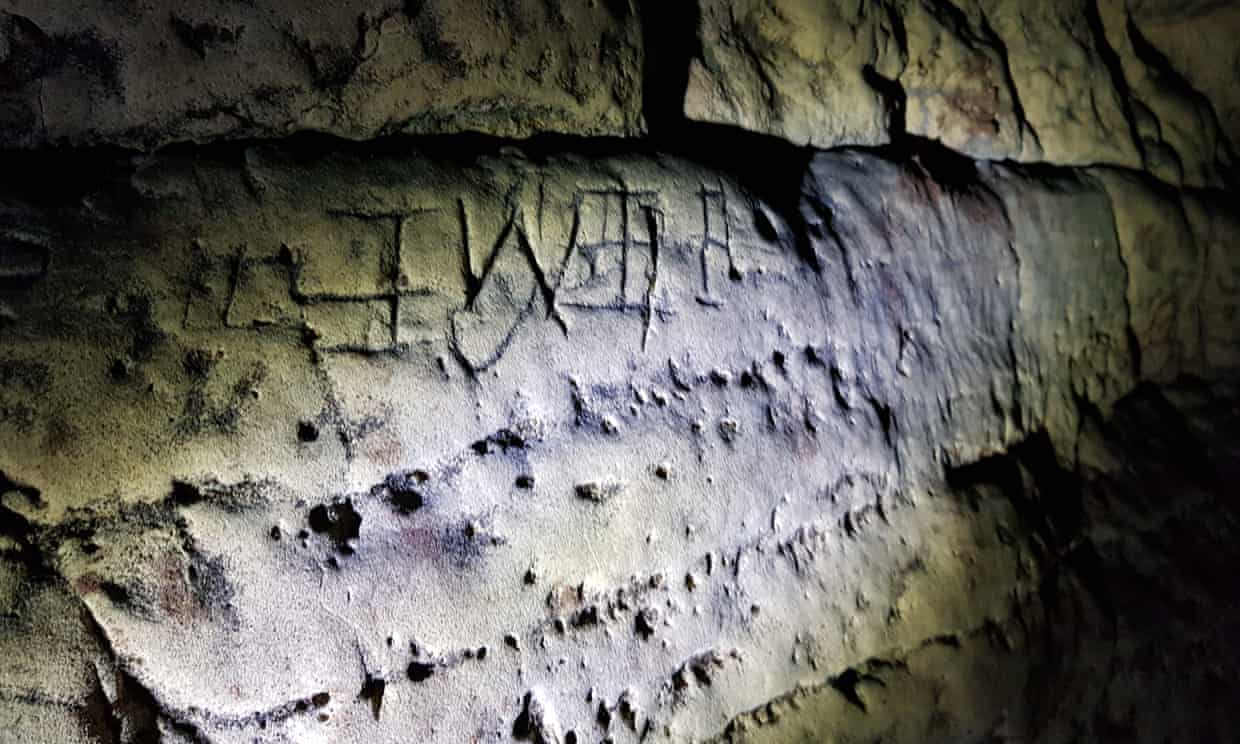

Recently, just such marking were found in a cave in England’s east Midlands, in the village of Creswell. The markings have been hiding in plain sight, so to speak, as it was only about two years ago that officials from the Creswell Trust, which governs matters concerning the cave, realized the pictures really were, and that they are hugely important.

The trust’s director, Paul Baker, told the press, “We had no idea!” when asked if anyone had seen the markings before. “Can you imagine how stupid we felt?” Until now the trust had told people there was little to see in Creswell’s cave but some Victorian graffiti.

Apart from the trust’s embarrassment about the lateness of the discovery, they are thrilled by the significance of the symbols, numbers and pictures, all etched into the limestone. Tantalizing though the drawings are, people cannot simply get down on their tummies, crawl in and take a look – at least not right now. It

is not accessible to the public for the time being because of coronavirus lockdown measures, but eventually it will open once again.

These are not the only ancient symbols found drawn in a Creswell cave; elsewhere in the post-medieval village is one that has Ice Age drawings of animals and birds that experts say are very early depictions of man’s attempts at art.

But Creswell Crags may have thousands of drawings, presumed to be the most found in any cave in the U.K. And surprisingly, they were stumbled upon by two locals simply exploring the cave.

Now, it is positively rife with experts of all stripes anxious to get a look at these symbols, put there hundreds of years ago to protect the village, and its citizens, from the evil that witches and other supernatural beings do.

Another Article From Us: Point Nemo: A Spacecraft Cemetery That’s Two Miles Under the Pacific Ocean

Baker suggested that visitors of a new sort may now begin arriving at the village, to see the place where England’s oldest cave marks were made, and the village they were intended to protect – against witches and the spells and sorcery in which they engaged.