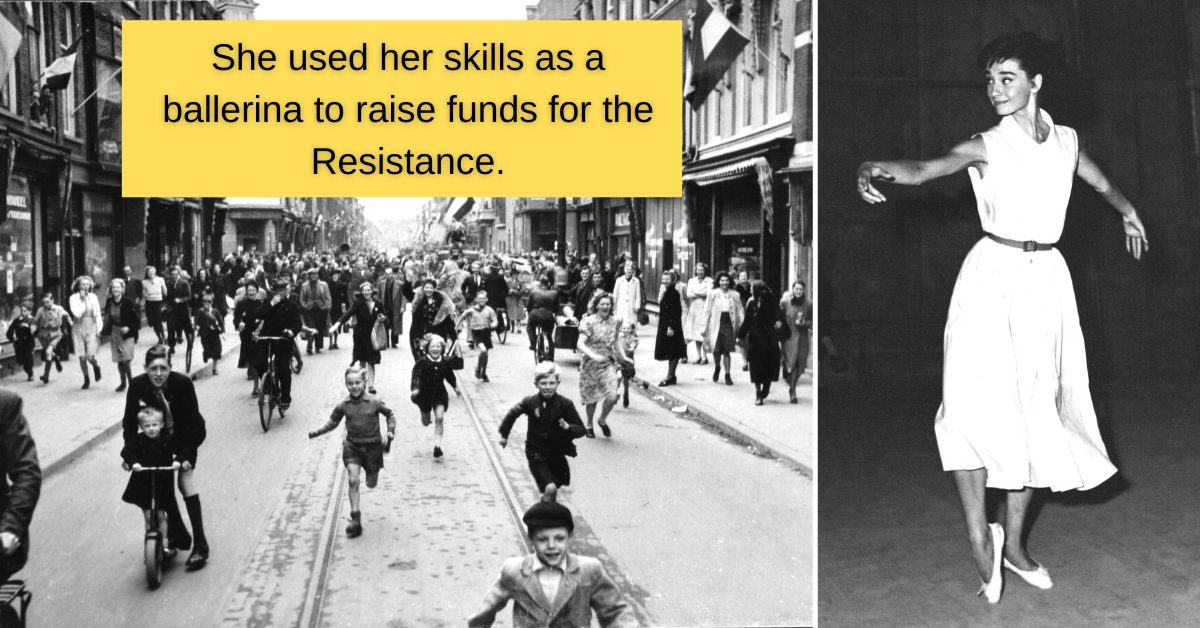

Audrey Hepburn lived a secret life as an asset of the Dutch Resistance during World War II. Hepburn’s work with the Dutch resistance as a child used her skills in the arts to raise money for underground groups.

She spent much of her childhood in occupied territory

The movie and fashion icon may have seemed too delicate to challenge the German forces. After all, she began life as an aristocrat, and her original career path was that of a ballerina.

But World War II changed everyone’s plans. Born in Brussels, she wound up in Holland with her mother, Ella. Neutral territory, or so they thought. The Germans moved in to occupy the country from 1940.

The half-decade German forces spent there made a savage impact. As described by author Robert Matzen in his 2019 book, Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II, the young star heard what appeared to be the screams of torture victims coming from a local bank-turned-prison.

In the village of Velp, near the city of Arnhem, food was withheld from the population. Matzen notes: “every life in Velp had been affected, if not outright ruined or taken away.”

Hepburn famously survived by eating tulip bulbs while sheltering from bombs in the basement. Underground spaces were essential for the Resistance — at one stage a Red Devil, or British pilot, was secreted by the group.

Audrey Hepburn’s work with the Dutch Resistance helped to raise funds

With many of the village’s prominent figures removed, responsibility for taking on the Germans lay with Dr. Hendrik Visser ‘t Hooft. In a piece for Den of Geek, he was described as “brazen enough to personally steal a German officer’s motorcycle and talk his way out of it.”

Robert Matzen shone a light on Hepburn’s wartime activities, as well as illuminating certain areas of the Resistance through her brave determination. She worked for the crusading doctor, becoming his assistant.

From the outside, this may have appeared to be a straightforward medical support role. Behind the scenes, though, things were much more dramatic.

Part of her job was that of a courier. The teenage Hepburn delivered messages to airmen who’d been shot down in the locality. At one point she came face to face with German soldiers. Her response was to pick some flowers for them and play the innocent…qualities that proved useful once she reached Hollywood!

Dr. Visser ‘t Hooft and others relied on youngsters to run the risk, knowing they wouldn’t be noticed as much. Hepburn’s English skills — she was educated in Kent — were invaluable for communications and formed a key part of his plans.

Hepburn — who was in her mid-teens by the time peace was declared — kept dancing. However, the backdrop to her performances was an increasingly sinister one. Performing at the City Theater in Arnhem, she drew the attention of off-duty German officers.

But she also took part in secret events to raise funds for the Resistance movement. Biography refers to her screen test for Roman Holiday, where movie types chatted to her about her experiences.

Hepburn “recalled performing ballet for audiences that were afraid to applaud because they didn’t want the [Germans] to catch them.” Matzen writes these were known as “zwarte avonden,” which translates to “black evenings,” so named because the venues had their windows blacked out or obscured to avoid detection.

During the screen test, Hepburn describes her covert dancing as “some way in which I could make some contribution,” as, she continued, the underground “always needed money.”

The interviewer asks her what the Germans thought of that. “They didn’t know about it” she replies, her face lighting up in the way cinema audiences came to love.

Matzen quotes Hepburn in an extract from Dutch Girl for Time magazine. She said her performances “amused people and gave them an opportunity to get together and spend a pleasant afternoon listening to music and seeing my humble attempts.”

When Allied forces arrived in the Netherlands, it signaled the end of her wartime life and the beginning of something better. Yet, as with many others, Hepburn was scarred by the conflict.

Her half-brothers Ian and Alexander were taken by the Germans to work in a labor camp. Uncle Otto, who she regarded as a father figure, was involved in opposing the occupation. To her horror, he was executed.

The war left its mark on her, even in later life

After treading the boards in Gigi, the rising star found herself courted by Hollywood. Roman Holiday (1953) was her first film and breakthrough role. Playing a carefree princess out on her own came naturally to Hepburn.

One role she didn’t accept was Anne Frank. Both girls were of similar age and spent the war in the Netherlands. Hepburn even read Frank’s story before the general public did — moving to Amsterdam, she and Ella lived above the editor who published the famous diary.

It was simply too hard for her to revisit this territory. Hepburn’s movie career bypassed World War II. She preferred not to acknowledge the life-changing conflict onscreen.

History.com notes that she “turned the image of the bosomy blonde Hollywood starlet on its head, presenting a new ideal of beauty for millions of moviegoers.” Hepburn was slight and slim, but what audiences didn’t know was that years of malnutrition during the war had contributed to this.

She left her turbulent past behind, though that meant some awkward truths needed to go with it. Hepburn’s parents supported the British Union of Fascists and were politically aligned with the occupying forces. Her father, Joseph, abandoned the family, and eventually, her mother dropped her fascist sympathies.

More from us: Tom Hanks And Steven Spielberg Build Epic World War II Base In England For New Series ‘Masters Of The Air’

Both Hepburn herself and studio bosses kept details such as this and the fact she danced for the enemy under wraps. Though, as Matzen points out, she had no choice but to do so. Refusal to perform for the occupiers didn’t seem like the best of moves.

Audrey Hepburn played many great roles. But her finest performance arguably took place before she earned her place in the Tinseltown firmament.