There’s a unique connection between science fiction and witchcraft: Johannes Kepler. To most, he is seen as one of the forefathers of modern scientific thought, debunking the long-held belief that the sun revolves around the Earth. The Imperial Mathematician to Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, he was the first to delve into astrophysics, and he developed a scientific way to predict eclipses.

Despite his ideas being deemed radical at the time, he helped to further the progression of scientific thought. However, there’s one particular aspect of his life that’s just as fascinating: his supposed connection to witchcraft.

Europe’s witch-hunt

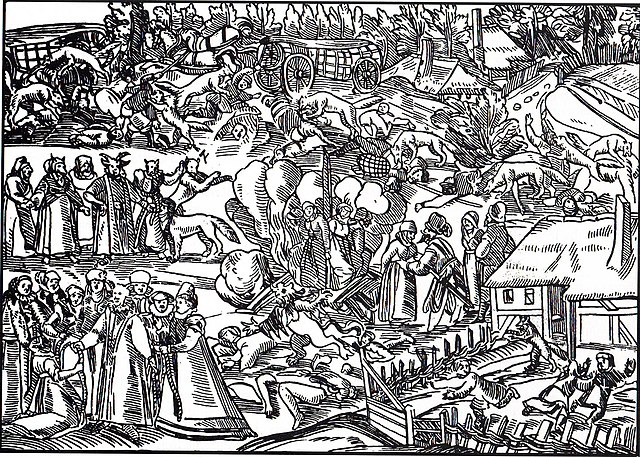

During the 14th and 15th centuries, Europe was entrenched in witch hysteria, wherein women were executed for “colluding with” the Devil. They were thought to have shied away from Jesus Christ and to have made a pact with Satan.

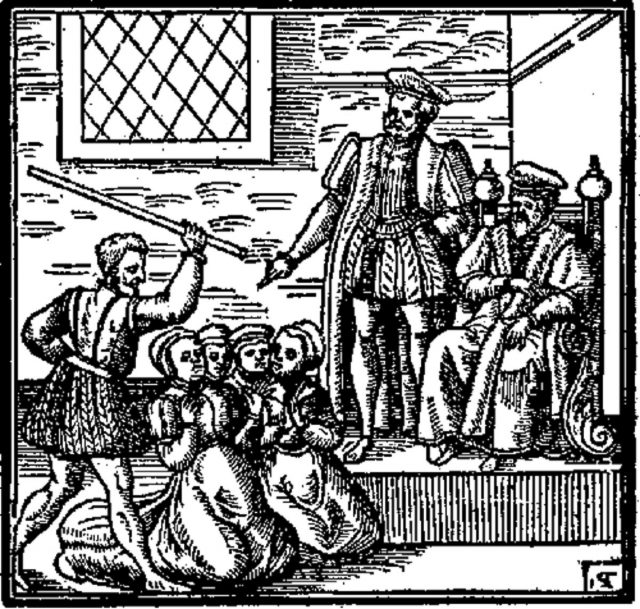

It was common for kings and their clergy to perform staged exorcisms on women believed to be possessed. Those in attendance witnessed insects crawling out of women’s mouths and odors emanating from their bodies as the “demonic” energy was purged from their systems.

Hundreds of thousands of women were put on trial for witchcraft, and the majority were executed.

Katharina Kepler accusations

Katharina Kepler, Johannes’ mother, was one of Leonberg, Germany’s oldest residents and was known for her brash manner. Those in the village were aware of her ability to mix herbal drinks, often offering aid to others.

In 1615, Lutherus Einhorn, the local magistrate of Leonberg, began a series of witch trials. Fifteen women were accused and eight executed for their supposed involvement in witchcraft. Katharina too faced accusations, which stemmed primarily from her feud with a local woman.

Ursula Reinhold was the sister of the village barber and a former friend of Katharina’s. She’d failed to repay a loan to the woman, and it was let slip she’d become pregnant by a man other than her husband and had sought an abortion.

Aware of the scandal the procedure would arouse, Ursula claimed she’d become ill not from an abortion, but by a spell Katharina had cast upon her. Given her elite village connections, the claim was uncontested.

Many others were persuaded to give accounts of her supposed sorcery, including a girl whose arm her mother claimed had gone numb after Katharina brushed against her, and a schoolmaster who claimed his leg had become paralyzed after ingesting a cup of wine whilst in her presence some 10 years earlier.

Other claimants accused Katharina of traveling through closed doors and causing the deaths of infants and livestock. Her son, Heinrich, is said to have claimed she’d “ridden a calf to death” and prepared a roast dish from it, an act he’d wanted to bring forth to authorities prior to the accusations of witchcraft.

Ties to Johannes Kepler’s work

The suspicions surrounding Katharina’s ties to witchcraft were further fueled by Johannes’ fictional work, Somnium (The Dream), wherein a young astronomer travels to the moon. He’s aided by his mother, an herb doctor with the ability to conjure spirits to assist him on his journey.

The work was Kepler’s way of introducing the masses to Copernicus’ heliocentric model of the universe, by blending scientific thought with allegory. He felt the fictional tale would be received better than his previous work. However, the majority of those who read the manuscript took parts of it to be autobiographical.

Many speculated the mother was actually Katharina Kepler. The result was her eventual arrest in 1620, some five years after the initial claims of witchcraft surfaced.

Trial and acquittal

Prior to his mother’s arrest and aware of the accusations against her, Johannes dedicated his time to her cause. He disproved the claims brought about by Ursula, showing she’d indeed had an abortion, along with those of the villagers. He proved the young girl’s arm had grown numb from carrying too many bricks, and that the schoolmaster’s limp was the result of him tripping into a ditch.

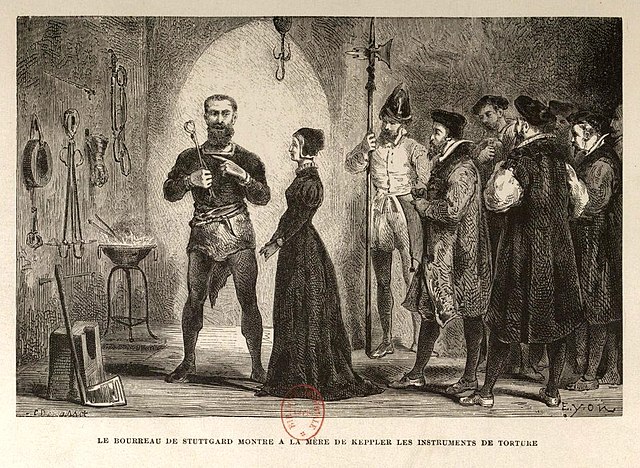

Many efforts were taken in order to get Katharina to confess. She was chained to the stone floor of a prison cell and threatened with being stretched on the wheel until she professed her guilt.

Katharina was acquitted of all charges in October 1622 and was released by order of the Duke of Wurttemburg, who decreed her refusal to confess as proof of her innocence. She died six months later, the trauma of the trial and her time in prison having taken its toll on her body.

The aftermath

Johannes spent the remainder of his life annotating The Dream, ensuring anything that could elicit superstitious interpretations was thoroughly explained. He did this by delineating his scientific reasons for using such symbols and metaphors.

More from us: When Smallpox Scars Were Used As Makeshift ‘Vaccine Passports’

He also looked into his mother’s societal circumstances. He found they were the result of her social standing, which kept her from opportunities of intellectual enlightenment. He broadened this observation, concluding the differing fates of sexes was not related to a higher power, but to society’s construction of gender.