There are hardly any similarities today with the 19th century. One thing that hasn’t changed is the abundant amount of wacky advice given to parents on how to raise children. Here are some of the most bizarre pieces of parenting advice from the 19th century.

A well-rounded diet

Victorian parents were instructed to give their children only the most nutritious food, and by nutritious we mean bland. Certain foods were thought to be dangerous and were a leading factor in indigestion.

According to George Henry Rohe’s Textbook of Hygiene (1890), any digestive derangements children faced were because they consumed “nuts, candies, pies, fruit-cakes and above all, pickles.” Fruit specifically should be avoided. Parents were told that their children should steer clear apricots, peaches, plums, raisins, and cherries at all costs.

So what could children eat? Well nutritious food, obviously. In this case, that food was limited to porridge, bread, and potatoes — but even those foods shouldn’t be served too hot or too cold. All food should be served lukewarm only. Snacks were usually not advised, but if absolutely necessary, then a child should be allowed to snack on a piece of “dry bread.”

Avoid anything green

A significant theme in Victorian parenting advice was the avoidance of anything green. Lydia Maria Childs in her 1831 guide The Mothers Book states that while a child is teething, they should never be given anything green to bite on.

Pye Henry Chavasse argues that a child should never be allowed to eat anything containing “yellow or green pigments” or even drink green tea for that matter. According to Chavasse, green tea made people nervous, and youths especially should “not know what it is to be nervous.”

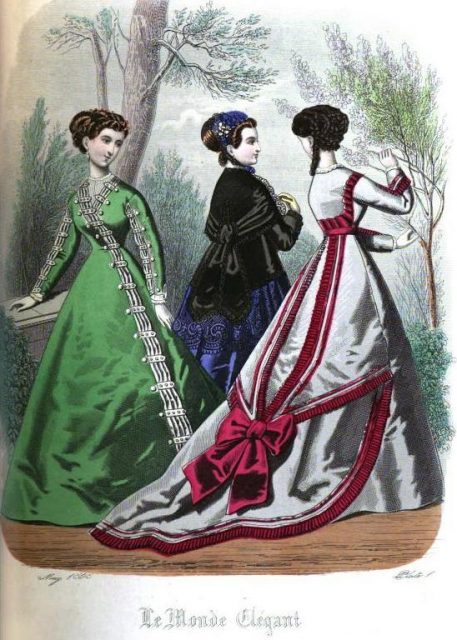

Oddly, Victorian advice writers were actually right to caution their readers against eating anything artificially green. In the 19th century, arsenic was used to dye various items deep green. Anything from wallpaper to dresses to fake flower petals contained arsenic to give them their deep color. However, the Victorians did not necessarily have an issue with arsenic — they just advised children not to eat it.

Sickness

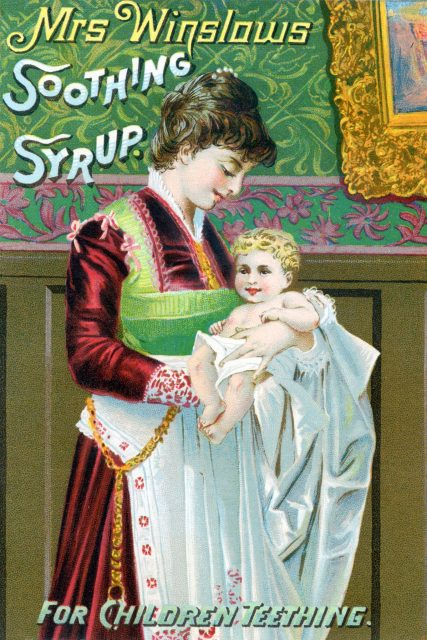

Speaking of arsenic, various poisons under the guise of remedies were prescribed to parents to give to sick children. Soothing syrups were commonly given to teething children often contained drugs or alcohol.

It was found that Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup’s main two ingredients were morphine and alcohol. This product was marketed as being able to soothe pain and diarrhea, and in 1868, it was reported that 1.5 million bottles of this soothing syrup were sold annually.

Mercury was also commonly used as a household medicine. William Horner marketed mercury as a cure for any ailment in his 1834 manual The Home Book of Health and Medicine, but he advised his readers to use it “cautiously.” Mercury was a common ingredient in many patent medicines of the 19th century, most commonly found in freckle creams.

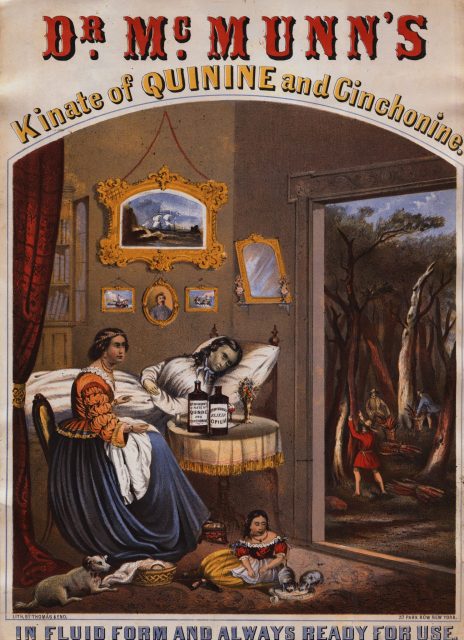

Opium was also often commonly used as a type of “miracle medicine” that could cure any sickness. Opium was often marketed as a painkiller, but parents also used it on babies and children to help cure colds or keep babies quiet. For example, Dr. McMunn’s Elixir of Opium was marketed as preventing “pain and irritation, nervous excitement and morbid irritability of body and mind.”

More importantly, though, Dr. McMunn’s Elixir of Opium was said to be “better than morphine.” It is no wonder that people of the 19th century began turning to these remedies to cure the various ailments being produced by injecting so many different drugs and poisons.

No reading and no fun

Because there was so little to do in the 19th century, one might think that reading was an ideal pastime. According to 19th-century parenting advice, this was the opposite of how children should spend their time. Both young girls and boys were advised to take caution when reading fiction as it was seen as too overstimulating for their underdeveloped brains.

This advice was primarily aimed at adolescent girls because it was thought that novels, parties, and the opera could bring on puberty too early. British doctor Edward J. Tilt in his guide On the Preservations of the Health of Women at Critical Periods of Life thought that reading romantic fiction would stimulate young girls too much, and worried that these girls would seek out romance in real life.

Boys too were advised to limit the amount of fiction they read, though it was more acceptable for them to be reading fictition books than it was for girls. William Jones advises his readers in Letters from a Tutor to His Pupils that although he does not think his readers should abstain from fiction, he did believe it to be the root of the “weakness of the human mind.”

If children couldn’t read, then what did they do for fun? Well truthfully, not much. One suggestion was to provide boys with a pile of dirt so they can make “dirt-pies.” Children should not be bought toys to play with, rather they should make their own to fill up their time. According to Lydia Maria Childs, even paper dolls were a serious business as they needed to be cut in a way that makes “little imitations to nature.”

Punishment

Of course, if children disobeyed their parents they needed to be punished. Much of 19th-century parenting advice literature promoted corporal punishment. The 1884 book A Few Suggestions to Mothers on the Management of Their Children advised mothers that a good old-fashioned flagellation with a thin, soft, old leather or carpet slipper is still the best mode of punishment — just ensure the ears are not struck.

However, if parents were getting tired of corporal punishment, advise writers outlined some more unique ways to discipline children. Lydia Marie Childs, for example, informed mothers to tie their children to chairs if they were misbehaving.

More from us: PBS’s ‘Hindenburg: The New Evidence’ Reveals Newly Uncovered Footage

Parents even had the option of waterboarding their children if they were misbehaving: Orson Squire Fowler, in his Self Culture and Perfection of Character: Including the Management of Youth advised parents to give their children a “cold bath” or “[pour] a pitcher of water” on their heads to subdue them.

Although the type of advice parents gave their children in the 19th century would never be given in the 21st century, one thing continues to remain the same. Children will refuse to take their parents’ advice well into the future.