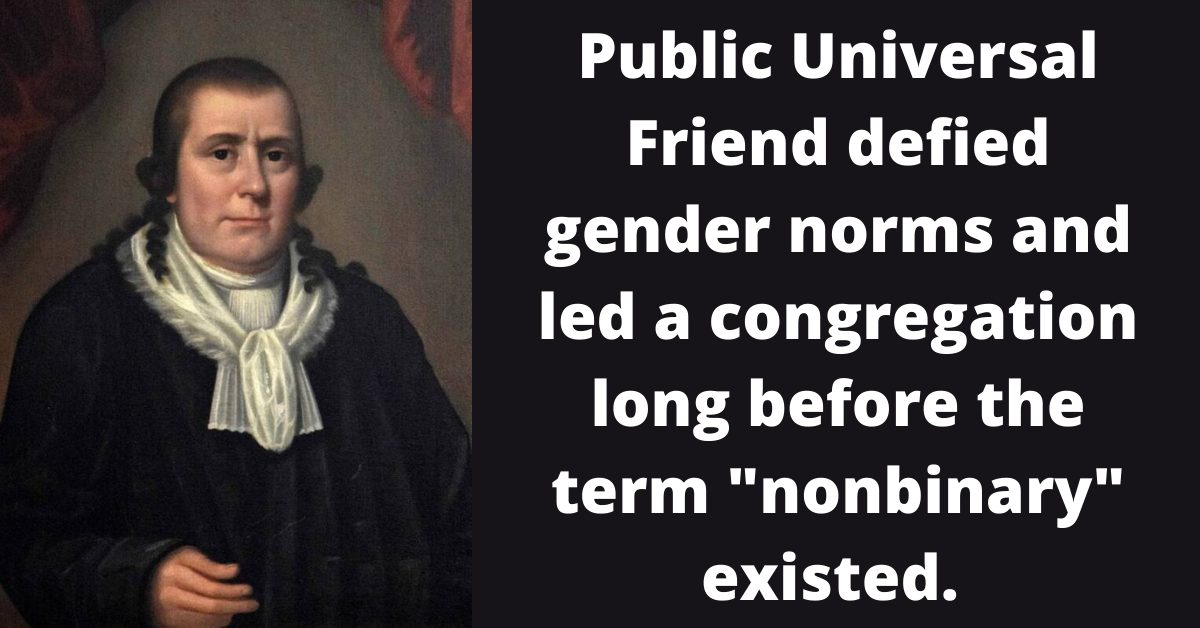

Public Universal Friend sounds like a virtual assistant, but they were actually what we would call “nonbinary” today, and they lived through the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Terms such as nonbinary weren’t in use back then. However, Public Universal Friend — or “the Friend” as they were also known — couldn’t be categorized as man or woman. Today’s commentators are reevaluating the life and legacy of this distinctive figure.

The Public Universal Friend was viewed as both sexes

Fueled by religious fervor, the Friend believed women “should be expected to obey only God — and not men,” as mentioned by All That’s Interesting.

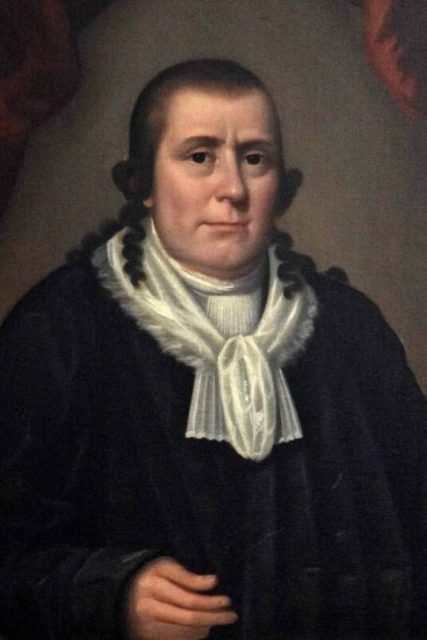

They began life as a woman. Jemima Wilkinson from Rhode Island was just 23 when a fever came close to taking her soul. Instead of dying, she was resurrected. Claiming a new name and dress code, she set out to change spiritual perceptions.

All That’s Interesting writes that Public Universal Friend “donned an unprecedented combo of feminine and masculine clothing.” Together with a hairstyle that was short at the front and long at the back, the Friend puzzled, inspired, and infuriated those they came into contact with.

The Friend themselves was quoted as saying: “I am that I am,” a scriptural reference that hints at their religious affinities.

The Friend thumped a Bible with the best of them

While appearing to subvert traditional ideas of gender, the Friend seemed happy to quote from established texts. Their chosen path may have been surprising to some. However, enlightening evidence was there on the page all along.

Labels were arguably not a feature of the Good Book. Reports highlight the Friend’s use of Galatians 3:28: “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

What was the Public Universal Friend’s religion? As Jemima Wilkinson, they had a Quaker background. Going forward, the Friend mixed Quaker and Baptist beliefs, according to a 2020 piece for The Washington Post.

Enough flocked to their cause, and the Friend began leading the Society of Universal Friends. Saddling up and touring New England, they spread the word.

In some ways, the times helped with group development. As Public Universal Friend was “born,” colonial America viewed belief through a different lens thanks to the First Great Awakening. The faith-based revival movement wanted to put women in the frame when worshipping higher powers. Already the established order was being challenged.

People subscribed to the Public Universal Friend’s way of thinking, but this enlightenment was short-lived

The Friend attracted a range of people to the Society. Rich associated with poor. Men with women. Though the tensions generated by their presence — notably a riot in Philadelphia — were present in the group also.

When the Society set up their own community in the “wilderness” of what became Yates County, New York, the name it took offered some hope: Jerusalem. This town should have represented the Friend’s ideals. Instead, disputes broke out.

Male identities came to the fore, asserting themselves. Dr. Paul B. Moyer, who wrote The Public Universal Friend: Jemima Wilkinson and Religious Enthusiasm in Revolutionary America, believes offended parties saw the sermonizing sensation as a challenge to male authority.

Released in 2015, the book also emphasizes the violent American Revolution (1775–83) that swept the nation during the Friend’s period in the spotlight.

The Friend wound up in court. There was an attempt to charge them with blasphemy. Ultimately, the judge decided that some verdicts are too much for a mortal jury.

The Public Universal Friend is described today as a historic nonbinary figure

Times change faster than people realize. Moyer has accommodated recent progress made by nonbinary people into his picture of the Friend’s life.

Speaking to NPR last year, he referred to Native American cultures that “have three, four, five or six different recognized gender categories.” He adds: “That generally wasn’t the case, you know, in 18th-century Rhode Island.”

As reported by the Post, he thought the Public Universal Friend came into being “primarily due to a religious calling.” Yet for him, this “does not make it any less sincere.”

More from us: High Fives: The Strange, Compelling History Of Slapping Skin

The Post quotes Tricia L. Noel, Yates County History Center’s executive director. In relation to the Friend’s ground-breaking work, Noel believes people are growing “a little more aware of the magnitude” of the story.

When Public Universal Friend passed away in 1819, the message departed with the medium. Two hundred years on, that vibrant legacy is being explored again.