Ancient Rome is seen as one of history’s most powerful civilizations. During its 1,000-year existence, it held a stronghold over Europe that many tried — and failed — to overthrow. Its emperors enacted, altered, and removed laws in order to fit the needs of society (and themselves). The penalties for defying these laws were often severe, but none more so than poena cullei, which is considered one of the Empire’s most cruel and unusual punishments.

Roman society was fundamentally patriarchal

Ancient Rome was inherently hierarchal. The oldest male was considered the top of the familial hierarchy, meaning he not only had absolute power over his immediate family, but also over the lives of his extended relatives as well. He held control over the family’s business and affairs and was given a wide berth in regard to doling out punishments to his children.

Given this stance, patricide — the killing of one’s father — was considered one of the worst crimes someone could commit. The Ancient Romans saw such an act as ungrateful and a threat to society as a whole. As such, it was handled in the most severe manner, as to dissuade others from committing a similar crime.

The introduction of poena cullei

The origins of poena cullei are debated. Some believe it began during the reign of Lucius Tarquinius Superbus between 535 and 509 B.C. Others think it first came about in the works of the Greek historian Plutarch. According to Plutarch, Lucius Hostius was punished for murdering his father. However, he doesn’t state how, or if, Hostius was actually executed.

The general consensus is poena cullei first appeared in Titus Livy’s History of Rome. In it, Livy describes how Marcus Publicius Malleolus was sewn into a sack and thrown out to sea in 101 B.C. for killing his mother.

Livy’s version of events appears tame compared to later versions of the punishment, which included the use of live animals.

The use of live animals

During the Early Empire, a live snake was sewn into the sack, with later writings introducing a monkey into the mix. The first recorded use of four animals appears in the writings of jurist Modestinus. He wrote in the third century A.D. that the tradition decreed by their ancestors meant that a necessary part of the punishment included not only a snake and a monkey, but a dog and a rooster as well.

Under Emperor Hadrian’s rule from 117 to 138, only those convicted of murdering their parents or grandparents were subjected to poena cullei. They were also given the option to choose whether to undergo the punishment or face another: being thrown into a ring with live animals, where they would be mauled to death.

Along with the use of live animals, other ritual punishments were performed before the accused was sewn into the leather sack. This included being beaten while their head was covered with a bag made from wolf’s hide (some state it was a leather bag). Wooden clogs were then placed on their feet before they were placed into the sack.

The punishment was altered over the years

Poena cullei saw many transformations. Those subjected to the punishment often changed, with some emperors reserving it for those guilty of murdering their descendants or ascendants, as opposed to just their parents.

Poena cullei eventually fell out of use. It was revived under the rule of Emperor Constantine the Great, who altered it to only include the use of a snake. He also widened the scope of those punished to include fathers accused of killing their children.

The punishment continued into the Byzantine Empire, under the rule of Emperor Justinian the Great. He reintroduced the rooster, the dog, and the monkey, and it remained the statutory penalty for parricide throughout the Byzantine Empire.

Poena cullei was eventually removed as the punishment for parricide around 892, in favor of another punishment: being burned alive… No one ever said the early Romans were a forgiving bunch.

Did the Ancient Romans actually use it?

It’s debated whether poena cullei was actually put into use. Some feel it was more symbolic, with historian Filippo Carlà-Uhink saying the male’s social status didn’t give them “carte blanche” to do as they pleased.

Another debate surrounds its logistics. Given the supposed difficulty of sewing not just a person, but live animals into a leather sack, many feel it wouldn’t have been practical. If it was actually used, did those charged with carrying it out think they were the ones being punished, too?

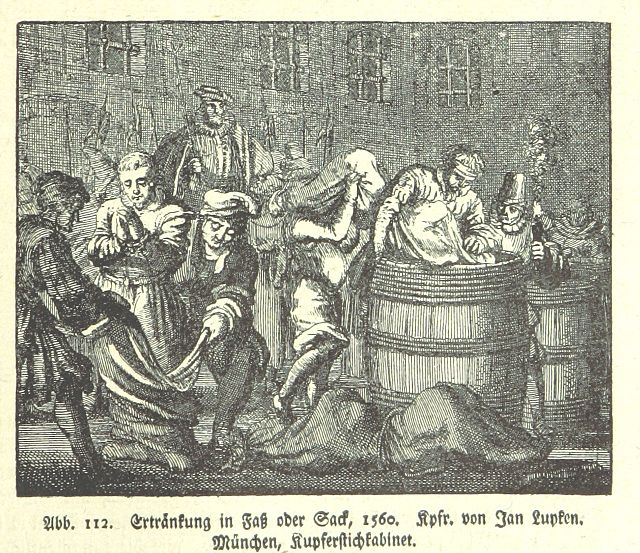

Poena Cullei saw a revival in medieval Germany

While the punishment fell out of use during the Byzantine Empire, it saw a revival in medieval and early modern Germany, with the last recorded use reported to have occurred in Saxony between 1734 and 1749.

As with their predecessors, the Germans had their own twist on the ritual. They changed the animals placed in the sack with the murderer, removing the rooster altogether and sometimes swapping out the monkey with a cat. One time, they omitted them altogether and sewed images into the sack instead, considering it to be a sufficient substitute.

The Germans also changed the material out of which the sack was made. While the Romans favored leather or hide, the Germans opted for linen. This changed how the prisoner died. Where before they were more likely to suffocate due to a lack of air, they were now subject to drowning due to the linen’s absorbency.

More from us: How A Cat Food Company Is Helping Save Coral Reefs

Poena cullei‘s use officially ended in Germany after it was abolished from Saxon law in 1761.