Computers can now identify and arrange ancient pottery fragments. This innovative use of machine learning will speed up the painstaking process, no doubt to the relief of archeologists everywhere.

Leszek Pawlowicz and Chris Downum of Northern Arizona University (NAU)’s Department of Anthropology have spent the past few years exploring the idea of tech-powered “sherd” analysis. Sherd is the term experts use for broken pottery.

Picking up the pieces has never been easier for archeologists

Convolutional Neural Networks, or CNNs, are central to the new approach. This branch of artificial intelligence “roughly emulates the thought processes of the human mind in analyzing visual information,” according to NAU.

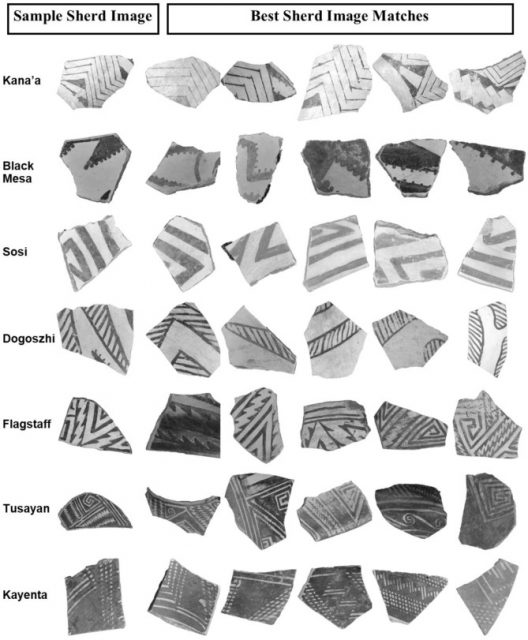

Referencing thousands of images showing decorated Tusayan White Ware, the trained machine “can objectively match a specific unclassified sherd image to its most similar counterparts through a search of thousands of digital photos.”

Pawlowicz and Downum’s findings are published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, from which the above quote comes.

As described by the American Southwest Virtual Museum, Tusayan White Ware is found in the region “bounded by the Little Colorado River, the San Juan River to the north, Chinle Creek on the east, and the Colorado River on the west.”

This AI machine learning process can draw staggering conclusions

The process involves identifying the pottery fragments by their design. In their statement, NAU write they are then grouped in categories that are linked to a certain time period and location.

Neural networks aren’t a replacement for human intelligence just yet, of course. A team of four flesh and blood experts were brought in to arrange visual samples for the CNNs to work with. These became what’s referred to by NAU as a “training set.”

Computers have a long way to go in terms of mastering the archeological knowledge of professors across the globe. That said, the results are impressive and potentially game-changing.

The University notes their machine “outperformed two of them and was comparable with the other two.”

Are neural networks and human intelligence the future of archeology?

CNNs are already delivering fast and accurate analysis in other spheres of study. CTV notes they are currently employed in “computer image recognition processes like comparing X-rays to medical conditions, matching images in search engines and in self-driving cars.”

Most importantly, they condense what ordinarily can take years for people to get their heads (and fingers) around. Skilled work by enquiring minds is always valued, yet the margin of error is arguably higher with the human brain.

NAU mentions the potential pitfalls of carefully sifting through artifacts, as opposed to putting photos of them under an AI-backed microscope. One thing machines may not do so much of is disagree. A drawback of having people in the mix is a tendency to draw different conclusions.

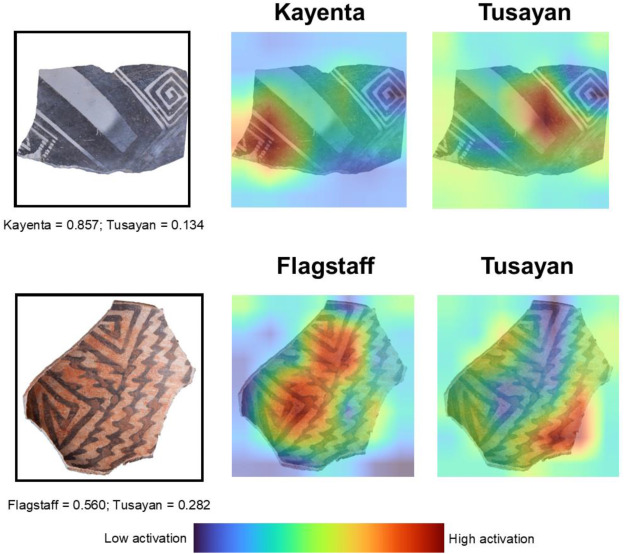

The university is encouraged by the machine’s ability to kind of explain its findings, too. Or at least let the team know what it was “thinking” when drawing conclusions. It reportedly does this through highlighting aspects of the pottery’s design with heat maps that are color-coded.

Speaking of heat, the CNNs take the fire out of potential disputes. Instead of experts poring over fragments and arguing over what piece belongs where, you have what could be a more objective view.

More from us: Ancient Hill Figure ‘The Cerne Giant’ Is Not So Ancient After All

One of the biggest impacts would be on locating single items of pottery. If a vessel is shattered, and different pieces are scattered in random places across a wide area, it would take a long time to find and put it back together. AI seems to offer a solution to this, with its relatively rapid methodology.

Might this lead to a smoother, more precision-engineered approach to sherd analysis? And if it does, is that entirely a good thing for archeologists, who may never need to dirty their fingernails again?