In June 2014, the novel The Girl with All the Gifts by MR Carey took the world by storm. The premise was that a fungal infection turned humanity into zombies. The fungus named in the book — Ophiocordyceps unilateralis — really exists in nature, except it infects ants rather than humans. Now, scientists have discovered an ant fossil that has brought a new species of zombie ant fungus to light.

The zombie ant fungus

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was discovered by Alfred Russel Wallace in 1859. While there are quite a few species of Cordyceps (parasitic fungi that infect insects), Ophiocordyceps only infects carpenter ants, which tend to be found in forests.

Generally, carpenter ants follow aerial trails through the trees, but if they are forced to cross the ground, they can become infected by Ophiocordyceps spores. The spores will land on the ant’s exoskeleton, eventually “drilling” into the ant’s body using a combination of enzymes and pressure.

Once inside the ant, the fungus infiltrates its muscles and circulatory system, forcing it to act in a specific way. The ant leaves its nest and climbs up a plant, then digs its mandibles into a leaf vein. Once it has done this, the mandible muscles quickly atrophy, ensuring that the mandibles are now set in a “death grip” and the ant won’t fall off.

What is so unnerving is that its final location is incredibly specific. The ant will travel to a point about 25–26cm (9.8–10.2 inches) above the forest floor and choose a leaf on the northern side of a plant in an environment. The humidity will be 94–95% and temperatures between 20–30°C (68–86°F). This is natural selection in action: if an ant climbs too high or chooses a different position, the fungus’s subsequent growth and its reproduction are hampered, so it doesn’t affect as many ants. But from the right spot, one ant can infect another 20–30 ants in a square meter.

Now that the ant is locked in position, the fungus can grow throughout its body. Eventually, the fungus’s mycelia push through the exoskeleton, and a fruiting body emerges from the ant’s head, ready to release spores and infect other ants. Sometimes, Ophiocordyceps spores can infect and decimate a whole colony.

The ant is trapped in its own body

A study in 2017 found an even more terrifying aspect of Ophiocordyceps. David Huges, an entomologist at Pennsylvania State University, conducted a series of tests that showed the fungus didn’t actually extend into the ant’s brain, something you might expect from a parasite that turns its host into a zombie.

Instead, the fungus secretes compounds that take over the central nervous system as well as metabolites that manipulate the brain. Once inside the ant, the single cells of the fungus join up to make connective tubes that run through the ant’s muscle tissues, allowing the cells to communicate and transport nutrients.

After Hughes’s student, Maridel Fredericksen, examined slices of infected ants no bigger than 50 nanometers thick (1/1000 of the width of a human hair), they found fungal cells throughout the ant’s entire body — but not in its brain. According to Hughes, speaking to The Atlantic, this study indicates that the fungus controls the ant’s muscles “as a puppeteer controls a marionette doll.” The ant’s brain is cut off from its muscles, effectively trapping it in its own body.

A precursor to Ophiocordyceps has now been discovered in amber

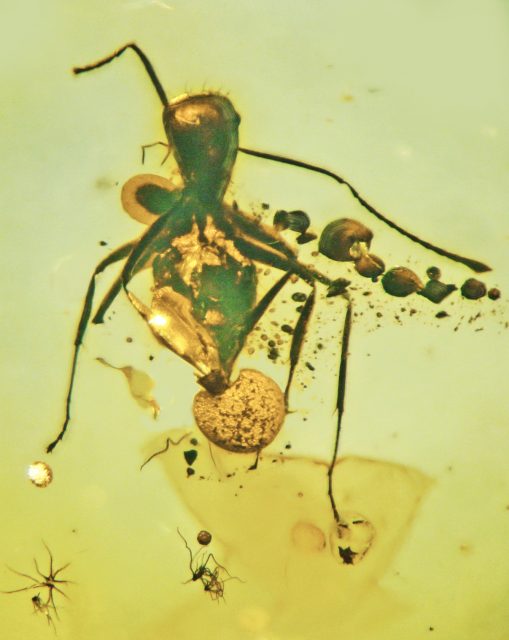

While working on an ant preserved in amber from Europe’s Baltic region, researchers identified a brand new fungus that existed over 50 million years ago. The study was conducted by George Poinar Jr., a paleobiologist at Oregon State University, and his French collaborator Yves-Marie Maltier. Poinar’s previous work in amber inspired the science in Michael Crichton’s book Jurassic Park.

The ant that fell victim to the new fungus (named Allocordyceps baltica by the researchers) was a carpenter ant, the same kind that is so susceptible to Ophiocordyceps today. However, this new fungus species displays several developmental stages not seen in Ophiocordyceps.

Poinar noted that a distinct difference between Ophiocordyceps and Allocordyceps was that the perithecia (flask-shaped structures that dispense spores) emerged from the fossilized ant’s rectum. When Ophiocordyceps infects an ant, that same structure emerges from the head or neck.

More from us: Coelacanth Fish Can Live Up To 100 Years, New Study Suggests

In a press release from the university, Poinar talks about the importance of this discovery. “This is the first fossil record of a member of the Hypocreales order emerging from the body of an ant. And as the earliest fossil record of fungal parasitism of ants, it can be used in future studies as a reference point regarding the origin of the fungus-ant association.”