The past year and a half has been nothing if not trying. The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world, and many countries are still fighting its spread. For many, it’s forced them to look back on the last epidemic the world experienced, the 1918 flu, also known as the “Spanish Flu.”

Just like the coronavirus, the Spanish Flu was a “novel” virus transmitted to humans from animals. It also put a large portion of daily life on hold. How do its symptoms compare to those presented by COVID-19, and how similar were the responses of political leaders and civilians?

Similar transmission

While the 1918 flu virus and COVID-19 derive from different viral families, they share a similar form of transmission. Both are primarily spread through respiratory droplets and aerosols, meaning coughing, sneezing, or even speaking in close proximity to others could result in their spread.

The transmission of both has also been connected to travel, with the 1918 epidemic having a clear source of spread: World War I. As the conflict in Europe drew on, soldiers from various countries converged on the continent, enabling the spread of new and existing diseases amongst themselves and vulnerable populations.

This, paired with the cramped and relatively unsanitary quarters soldiers lived in, it’s no surprise the virus spread.

Limit contact

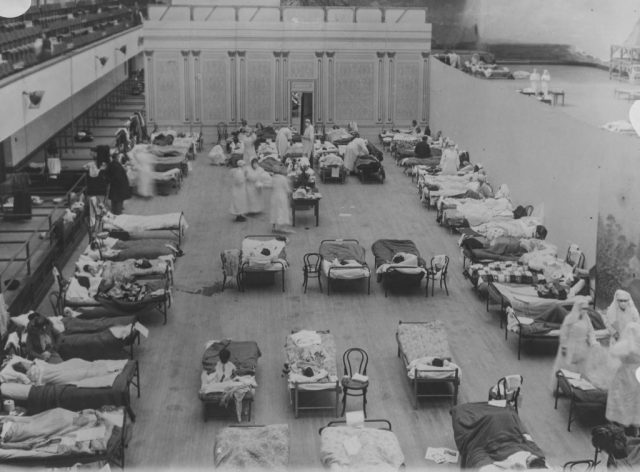

The one message spread by medical professionals during the coronavirus pandemic has been the importance of limiting our contact with others. Governments have accomplished this through a number of measures, including lockdowns, school closures, and extensive quarantine measures. They’ve even discouraged the use of public transport and have limited the hours during which businesses can be open.

The same message was shared in 1918, with those in power saying the best chance of controlling the spread of the virus was to quarantine and obey public health measures. Unfortunately, just like today, many disregarded the advice, going so far as to say it was propaganda.

Halt all travel

When it became evident the COVID-19 virus had undergone a worldwide spread, the majority of countries closed their borders to international visitors and ordered their residents to stay home. Travel is a key way in which the virus has moved between countries, so many governments limited the movement of citizens.

Initially, people were encouraged to travel during the 1918 epidemic, as officials believed travel to the countryside would allow the worst of the virus to be avoided. It was quickly learned that travel was actually one of the ways the virus propagated, and from then on it was ill-advised.

The difference in remedies is…interesting

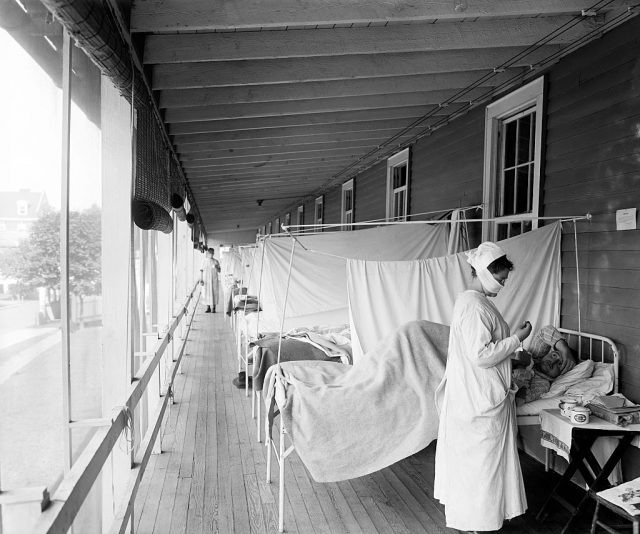

Doctors have been promoting the effectiveness of the coronavirus vaccine since different iterations were produced, but back in 1918, no such vaccine existed to combat the Spanish Flu. While hand-washing and staying home when sick were prompted as effective countermeasures, other remedies were much more questionable.

There was a push for people to take in as much “pure” air as possible, with Surgeon General Rupert Blue stating, “Keep out of crowds and stuffy places as much as possible […] The value of fresh air through open windows cannot be overemphasized […] Make every possible effort to breathe as much pure air as possible.”

That isn’t even the most curious of proposed remedies. Some of the more unique ones included rubbing oneself with an onion, ingesting digitalis (which is incredibly poisonous), and rubbing one’s feet to prevent infection, among others.

Different age groups are affected

Both the 1918 flu virus and COVID-19 targeted those of a lower socioeconomic status. They were also especially harmful to pregnant women and those with pre-existing conditions. However, the age groups they affected are rather different.

While everyone is at risk of getting sick from the coronavirus, those who are older are more likely to become severely ill. The risk begins to increase in your 50s and only gets higher the older you get. The majority of children don’t experience symptoms if they contract the virus, and young adults are less likely to become hospitalized.

On the flip side, the age range considered relatively safe when it comes to COVID-19 was the one most at risk in 1918. The virus devastated those between the ages of 20 and 40. It’s estimated between 17 and 50 million worldwide died after contracting the virus.

Anti-maskers, then and now

Doctors today and back in 1918 have advocated for the effectiveness of masks when it comes to preventing the spread of viruses. In 1918, they were typically made from cheesecloth and gauze, and people were encouraged to wear them both indoors and out. There were even some who framed wearing them as a patriotic action.

Those who refused to wear a mask were called “mask slackers” and risked fines if they lived in cities where mask-wearing was mandatory, similar to today. Opposition to them was strong and many called them “dirt traps.” There were some who even poked holes in them, so they could smoke cigars without being fined by the police.

Differing political responses

It’s difficult for the world to go through a pandemic without it becoming politicized. This was as true during the 1918 flu epidemic as it has been with COVID-19. When looking at the United States in particular, the responses from both eras could not be more different.

Over the past year and a half, the country has been run by two different presidents with differing views. Whereas Trump preemptively claimed the country had beaten COVID-19, despite medical experts saying the opposite, Biden has pushed for vaccination and the spread of medical information.

Back in 1918, however, the country was met with a completely different response: silence. President Woodrow Wilson refused to talk publicly about the epidemic, something he has been criticized for by historians, and instead decided to focus all his attention on the war effort. This was despite he himself being afflicted with the virus!

Differing symptoms

While at first the symptoms for the coronavirus and the Spanish Flu might appear to be similar, they are actually fairly different. The world has had to endure numerous waves of COVID-19 and what doctors have learned is that it affects everyone differently. Some patients experience mild or no symptoms, while others get so sick they have to be hospitalized and put on a ventilator.

While the virus typically presents itself with flu-like symptoms, the most unique symptoms of the coronavirus are the potential loss of smell and/or taste. There’s also the fact that some individuals experience symptoms long after recovery, including lasting fatigue and coughing.

More from us: School Life In The 1950s And 1960s Was Really Its Own Thing

Just like COVID-19, the 1918 flu came in waves. While the first was relatively mild, the second and third were much worse. The second wave was devastatingly deadly. Those who contracted it risked dying days, even hours, after showing symptoms. Their lungs became a battlefield, and oftentimes individuals would die from a lack of oxygen because their lungs had filled with liquid. A tell-tale sign of this was the blue tinge their skin would get before they suffocated.