The history books frequently record Frederick Cook as a man who claimed he reached the North Pole in 1908 — but didn’t. However, what has been forgotten over time is that Cook actually pioneered the first use of light therapy and diet to combat scurvy in a method that he named “the baking treatment.”

The sailor’s worst enemy

Scurvy is a disease that comes about due to a lack of vitamin C in humans. After a month or more without this important vitamin in a person’s diet, they’ll start noticing the first symptoms: lethargy, shortness of breath, gum disease, and muscle pain. As the disease develops, teeth might be lost and skin will start to bruise easily. Fever, convulsions, and jaundice follow — and ultimately death if left untreated.

Today, with a healthy diet rich in nutrients, the average person doesn’t need to worry about scurvy. But in the past, scurvy could have a devastating effect on sea voyages where up to half the sailors would perish with it before the end of the trip.

In 1753, Royal Navy surgeon James Lind convinced the world that citrus fruit was the answer to scurvy. By 1795, the Royal Navy was giving its sailors lemon juice to ward off the disease.

But this treatment hit a snag: during long voyages, any citrus fruit on board would go rotten. The Navy tried stocking their ships with lime juice from the Caribbean, but even that lost its potency over time.

Exacerbated by the ends of the earth

The existence of vitamin C wasn’t discovered until the 1930s, so ships’ surgeons were constantly trying to guess what caused the disease and what would cure it. Scurvy was a particular problem for polar expeditions, where the inhospitable environment denied explorers fresh food and timber for fuel.

But a chance decision on one Antarctic expedition not only saved the sailors of that ship but influenced the man who would go on to be the first explorer to reach both poles.

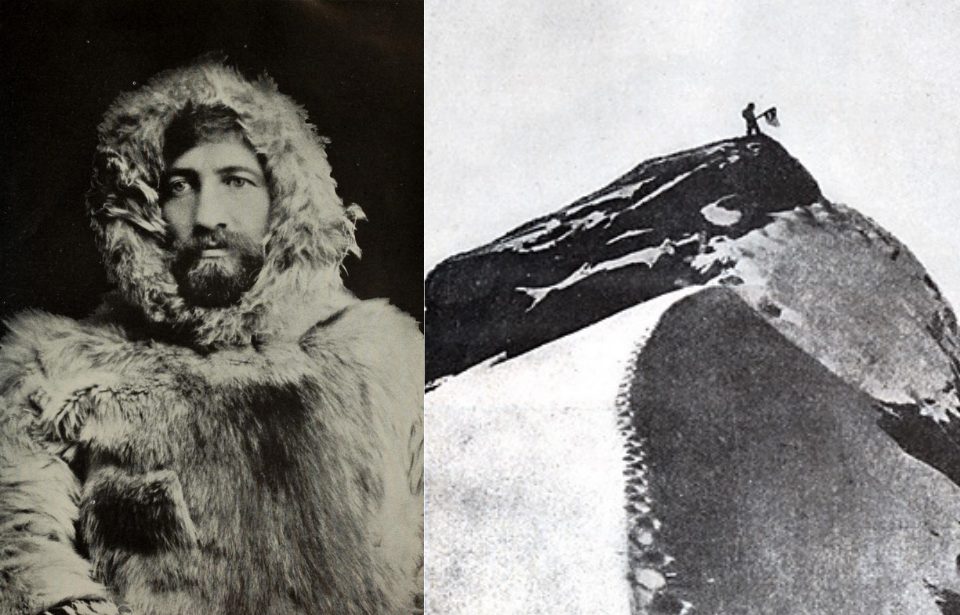

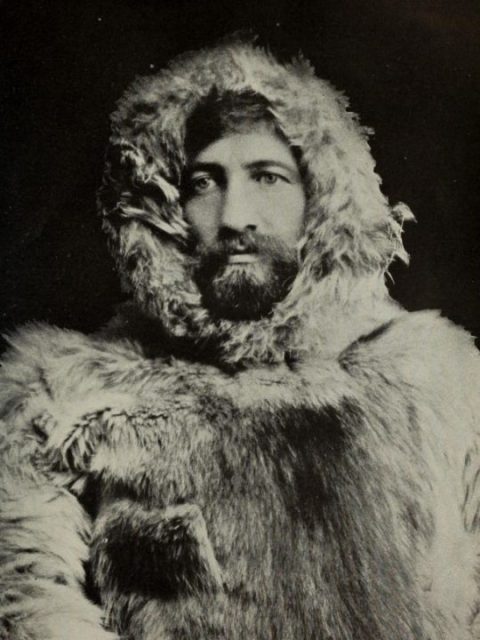

Frederick Cook and his disputed claim

Frederick Albert Cook was an American born to German immigrant parents in 1865. He completed his medical studies at New York University Medical school in 1890.

He was the surgeon for Robert Peary’s Arctic expedition that took place between 1891 and 1892 and also on the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897 to 1899.

After several Arctic and Antarctic expeditions as part of a ship’s crew, he tried to reach the North Pole in 1907, accompanied by two Inuit guides named Ahpellah and Etukishook. The three of them set off from Greenland in February 1908 and were gone for 14 months.

Cook’s claim that he reached the North Pole during this trip was widely believed. But rival explorer Robert Peary, who claimed that he reached the North Pole in April 1909, cast doubt on Cook’s claim. In December 1909, a commission at the University of Copenhagen examined Cook’s (somewhat sparse) evidence of his expedition.

Cook claimed that he had made detailed records of his trip but had been forced to leave them in Greenland with Harry Whitney, an American hunter associated with Peary’s rival party. When Whitney tried to bring the records back with him in 1909, Peary refused to let them on his ship, so they were abandoned in Greenland.

Cook’s claim was discredited, and he spent the next few years trying to defend it. Although Peary’s claim was considered true for a number of years, it, too, was eventually proven false.

The Belgica and the baking treatment

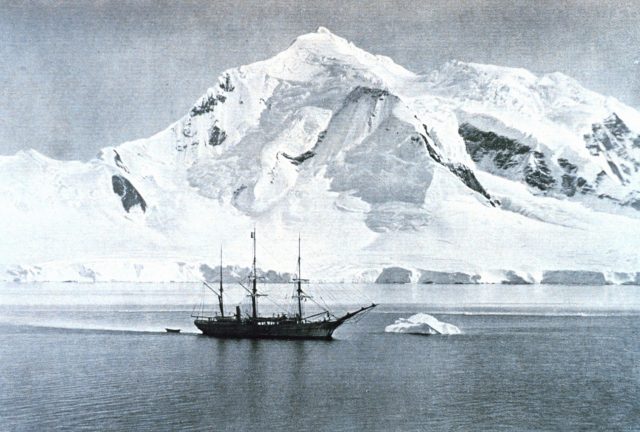

In his new book, Madness at the End of the Earth, Julian Sancton details how Cook saved the life of a crewmate when he served as surgeon on the Belgica, a ship that ended up imprisoned in the Antarctic ice for more than a year.

In an article for Time Magazine, Sancton tells how Cook woke on the morning of July 11, 1898, to find Captain Georges Lecointe crawling towards him. All the men were suffering from scurvy, but now the captain seemed partially paralyzed. Trusting the skills of his surgeon, Lecointe said he’d follow whatever instructions Cook gave him.

During Cook’s previous expeditions, he had mixed with the Inuit in Greenland and had noted that they didn’t suffer from scurvy, despite the lack of citrus fruit and fresh vegetables. He surmised that something in their diet — which mostly consisted of fresh Arctic game such as caribou, walrus, and seal meat — warded off the disease.

In a leap of medical faith, Cook ordered Lecointe to drink nothing but water and eat nothing but seal and penguin meat. He also instructed the captain to strip off his clothes and stand before a blazing fire three times a day. In a week, the paralysis was cured, and the other crew members were all eager to try this new diet and “baking treatment.”

It appears that Cook invented the first use of light therapy, something which is used today to treat seasonal affective disorder and some forms of depression.

The sun had last been seen by the Belgica two months before, and he surmised that the lack of light was taking a dire toll on the men. Sancton claims that this diagnosis was also drawn from Cook’s interactions with the Inuits. Apparently, one Inuit elder led Cook to think that light could be stored in the body just like nutrients, and he came to believe that “the presence of the sun is essential to animal as it is to vegetable life.”

Medicinal benefit or the convictions of an ingenious fraudster?

It’s unclear whether exposing the sailors to firelight was as beneficial as soaking up sunlight. It might simply have been the case that being warm and dry after months in the Arctic was as important to their mental health as the extra fresh meat was to their physical health.

Sancton’s article in Time Magazine expands on that theory by suggesting that Cook’s exuberant and endearing personality assisted with a placebo effect.

Cook conducted regular surveys of his patients’ mental health, writing that it was his duty “to raise the patient’s hopes and instill a spirit of good humor.” When Cook ended up in prison for financial fraud years later, Sancton writes how he “became one of the most popular inmates, beloved just as he had been aboard the Belgica.”

Cook’s methods directly influenced the first man to reach both poles

One of those on board the Belgica was Roald Amundsen. He learned from Cook that the best way to survive in the Arctic was to ensure you had plenty of fresh meat. This would help him become the first person to reach the South Pole 13 years later.

In his book, Sancton describes how the rest of the crew hated the cooked penguin steaks, but Amundsen was happy enough to eat them raw: “He pronounced it ‘the most delicious steak could you wish for’ while everybody else found it absolutely repulsive… he loved being able to do what other people didn’t have the courage to do or felt incapable of doing.”

Interestingly, cooking seal or penguin meat will destroy the vitamin C in it, so Amundsen was getting the highest dose possible with his strange eating habits.

More from us: New Quest Planned To Search For Shackleton’s Endurance In The Frigid Waters Of The Antarctic

This adherence to Cook’s tried and tested diet was one of the reasons that contributed to Amundsen making it to the South Pole and back again while Robert Scott and his team perished in their attempt.

Speaking in later life, Amundsen called Cook “a genius and the finest traveler he ever saw.” He was convinced he owed Cook his life too, so when the former surgeon was imprisoned for fraud in November 1923, Amundsen would visit him frequently.