The Greatest Showman starring Hugh Jackman as the infamous American entrepreneur has become a modern classic. It was released in 2017 and is still a popular option for outside cinema events and themed kids’ clubs.

But while Hugh Jackman might have won the hearts of audiences with his portrayal of a driven man who would nevertheless do the right thing on his way to success, the real PT Barnum was quite different.

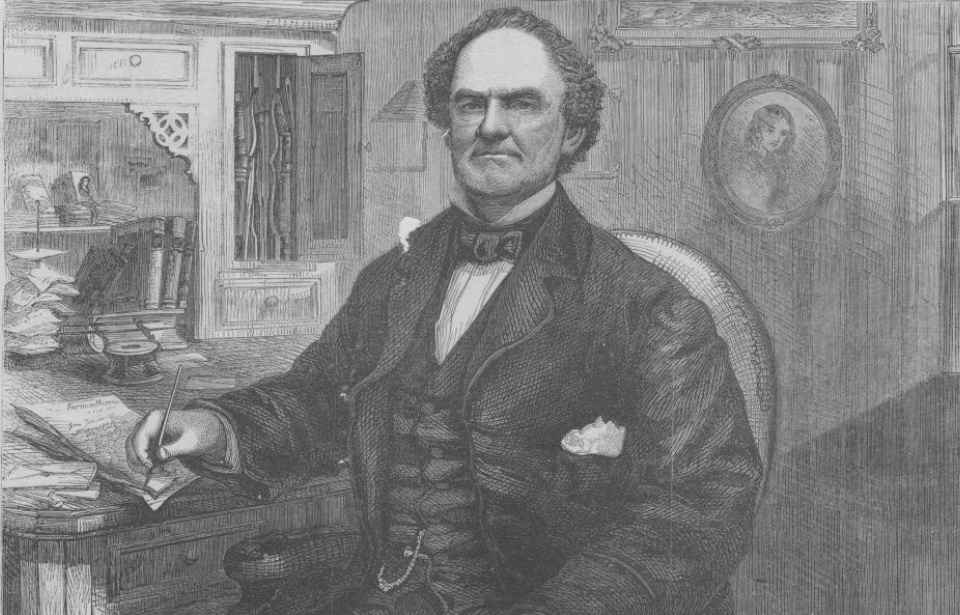

Early life

Born in July 1810, Phineas Taylor Barnum had several jobs before reaching success. These included being a lottery manager, shopkeeper, and newspaper editor. He ran a boarding house at one point and worked in a grocery store. He married his childhood friend Charity Hallett in 1829.

His big break came in 1835, when he was 25 years old and learned about Joice Heth, a woman who claimed to be the 161-year-old former nurse of George Washington. He agreed to “rent” her for a year at a cost of $1,000. He was easily able to repay that sum after earning an estimated $1,500 a week from exhibiting her.

Although it was the real Barnum’s big break, this episode from his life is not included in the film. Instead, Hugh Jackman’s character is seen as being laid off and using the opportunity to finally chase his dream. This is probably because Barnum was ruthless in his treatment of Heth. He exhibited her 10 to 12 hours a day, despite her being blind and almost paralyzed.

When she died, he still found a way to make money from her: by charging 1,500 spectators 50 cents each to watch her autopsy.

Barnum’s American Museum opens for business

Barnum opened his American Museum at the corner of Broadway, Park Row, and Ann Street in lower Manhattan in 1841. The building had originally been Scudder’s American Museum. Under its new owner, the museum attracted around 15,000 visitors a day at 25 cents a time.

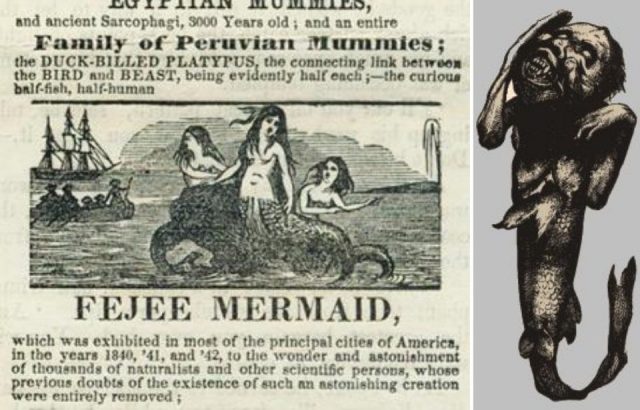

There was a mixture of exhibits including a zoo, museum, lecture hall, wax museum, theater, and freak show. Exotic living animals were mixed with hoaxes such as the Feejee mermaid and “living curiosities” such as the Aztec children and the Siamese twins.

In contrast to the film, Barnum met Charles Sherwood Stratton a year after opening, when he was only four years old and measured only 25 inches. Barnum trained the boy to sing and dance under the persona of General Tom Thumb.

He was not the first curiosity that Barnum recruited, and it’s doubtful that the museum owner hired him in an effort to give the diminutive man a sense of purpose and dignity, as is shown in the movie.

In fact, Barnum claimed that the four-year-old was actually eleven, and as well as teaching him how to imitate people like Hercules and Napoleon, Barnum had the child drinking wine at age five and smoking at age seven, all to add to his illusion.

A keen marketer or a con-man?

While Hugh Jackman’s character uses various marketing tricks to get people to attend his museum, they are nothing to the sly practices of the real Barnum, who would deliberately publish articles claiming that his exhibits were fakes.

When people read these claims, they were inspired to come back and see these exhibits for themselves. There were also rumors in 1853 that his bearded woman known as Madame Clofullia was really a man, leading to her examination by doctors and the pronouncement that she was, indeed, a woman.

One famous exhibit missing from the film is the Feejee mermaid. Rather than being an attractive half-fish woman, the Feejee mermaid was described (by Barnum himself in his autobiography) as “an ugly dried-up, black-looking diminutive specimen about 3 feet long. Its mouth was open, its tail turned over, and its arms thrown up, giving it the appearance of having died in great agony.”

Barnum leased the creature for $12.50 per week. He got his assistant, Levi Lyman, to pose as “Dr. J. Griffin,” the man who had discovered this wonder in South America. In reality, the mermaid was the torso and head of a small monkey sewn onto the bottom half of a fish.

According to the Museum of Hoaxes, Barnum ensured that a woodcut of mermaids appeared in the major papers on Sunday, July 17, 1842, whetting the public’s appetite for this marvel.

There was no affair with Jenny Lind

It seems fairly clear that, in reality, Barnum didn’t cheat on his wife with opera singer Jenny Lind, causing Charity to leave him. A Vanity Fair article from 2017 notes that a lot of accounts about Barnum hint at “the tension of a man torn between his steady, Puritan wife and an exotic European songstress.” But this was not the case.

Jenny Lind’s nine-month tour with Barnum took in the equivalent of $21 million. Before that, she’d officially retired from opera, with Queen Victoria attending her final performance in 1849. But Barnum lured her out of retirement, even though he’d never even heard her sing.

He wanted to establish himself as a more respectable showman, so he made some extraordinary offers, such as paying Lind $1,000 a night for 150 performances. His knack with publicity helped ensure the tour was a hit.

However, the film was accurate in claiming that Lind ended the tour early. After 93 concerts, she terminated her contract with Barnum. However, that wasn’t because of a love affair, but reputedly because she was uncomfortable with Barnum’s marketing strategies.

In fact, in his biographies, Barnum expresses a deep love for his wife, describing himself as “the husband of one of the best women in the world.” He stayed with her until her passing in 1873, at which point he married Nancy Fish, who was 40 years his junior.

It all goes up in smoke

Just like in the film, Barnum’s museum building burned down in July 1865. The cause of the fire was unknown, but some think that this was more likely due to Barnum’s Unionist sympathies. A Confederate arsonist had tried to start a fire there the year before in response to Barnum’s pro-Unionist lectures and exhibits. So although the building did burn down, it was probably due to politics rather than outrage at Barnum’s exhibits.

There was a heroic rescue during the fire, but not the one depicted in the movie. In researching The Greatest Showman, the website History vs Hollywood found that the characters of Phillip Carlyle (Zac Efron) and Anne Wheeler (Zendaya) were entirely fictional. There were no romantic heroics that night, but there was a hero on hand.

Many of the animals on display at Barnum’s Museum tried to flee the building, tragically being killed when they got outside in case they presented a danger to the public. Fireman Johnny Denham allegedly killed a tiger with an ax before rushing into the burning building, returning soon after carrying a 400-pound woman on his shoulders.

Circus master

Barnum opened a new museum nearby, but that also fell prey to a fire in March 1868. After that, he took another direction and set up the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1871. Barnum teamed up with Dan Castello and William C. Coup, who already owned a circus. Unlike the movie where Barnum opens his circus as a young man, he was actually in his 60s before he took this step.

At first, it was a traveling circus named Barnum’s Grand Traveling Museum, Menagerie, Caravan, and Hippodrome, although this title was shortened to “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

By 1875, Barnum had obtained full ownership of the circus. That year, he was also elected mayor of Bridgeport, Connecticut, his hometown. During his term of office, he helped found the Bridgeport Hospital.

After Barnum passed away, the show was taken over by his rivals and became the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Combined Shows in 1919.

The circus continued until its final performance in May 2017. It was shut down after being hounded with controversy about alleged animal abuse and exploitation. The cruel treatment of animals was certainly something that was present in Barnum’s time when he kept beluga whales in a 576-square-foot tank in the basement. When the animals perished after a short time, he’d secure new ones.

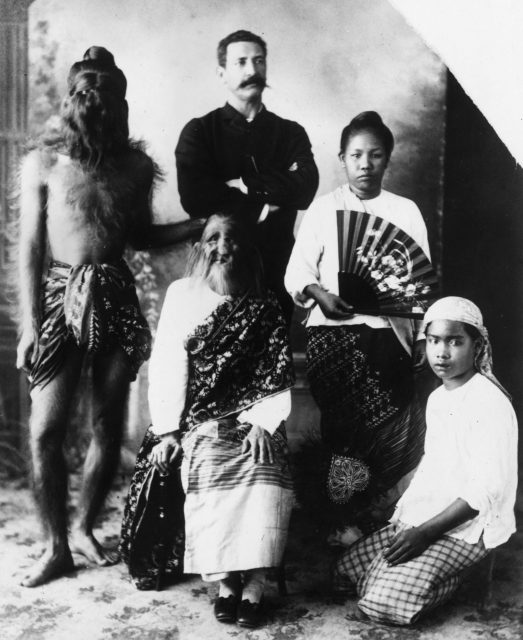

Exploitation rather than enhancement

Throughout his career, Barnum seemed content to exhibit people as property, exploiting them as freaks and curiosities. James W. Cook, professor of History and American Studies at the University of Michigan, wrote a book entitled The Art of Deception: Playing with Fraud in the Age of Barnum. He charts how Barnum’s attitude to slavery changed when he ran for Congress. At that point, Barnum admitted that he’d owned slaves in the past and regretted his actions.

Benjamin Reiss, professor and chair of English at Emory University, commented in The Showman and the Slave: “People change and it’s possible he really did feel this.” But even if he did change his mind, Reiss notes that Barnum “had these new ways of making racism seem fun and for people to engage in activities that degraded a racially subjected person in ways that were intimate and funny and surprising and novel.”

More from us: Unexpectedly Bizarre Photos of Historical Figures and Celebrities

Perhaps Phineas Taylor Barnum was, indeed, “The Greatest Showman” — but his life, which was filled with shams and exploitation, is a reminder to us that Hollywood fiction is often rather different from real-life facts.