A charismatic figure provided lucky investors with access to an exotic getaway back in the 19th century. The catch? It was pretty major. Turns out the land of Poyais in Honduras was pure invention.

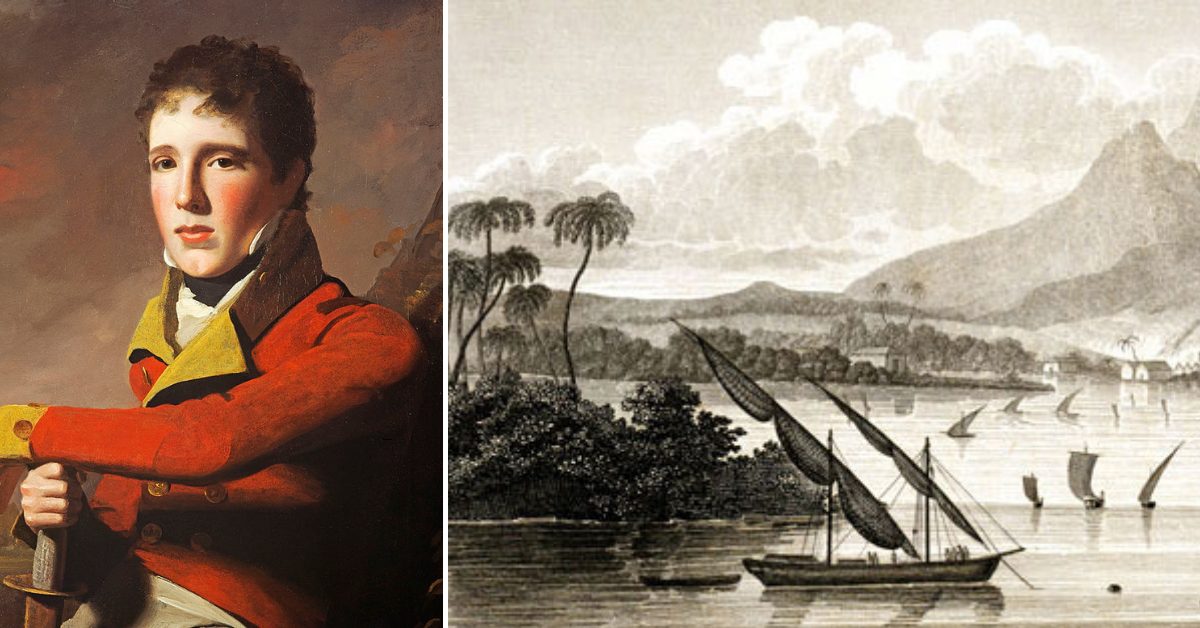

Brigadier-General Gregor MacGregor of the Venezuelan Army had spun a web worthy of Peter Parker. But how did he get away with his crimes?

MacGregor’s Poyais pitch

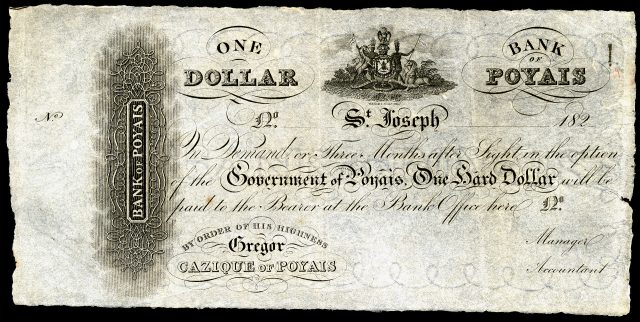

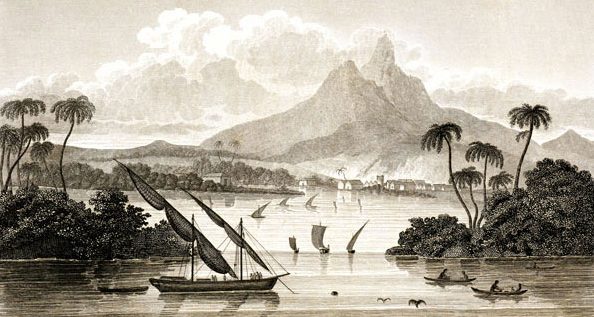

MacGregor told folks he was the Prince, or “Cazique”, of Poyais. The territory, supposedly part of Central America, featured lush and astonishing sights.

An abundance of juicy fresh fruit, exotic local wildlife, and clear water was ready and waiting for those bold enough to open their wallets. Historic UK writes that MacGregor pursued “an extensive infrastructure project”. He produced a substantial guidebook to further flesh out his vision.

Shares brought in hundreds of thousands of pounds for the silver-tongued salesman. By today’s standards, he wound up a billionaire, according to BBC Future. They posted an excerpt from Maria Konnikova’s 2016 book The Confidence Game.

Speaking of wealth, MacGregor revealed that “chunks of gold lined the riverbeds.” There were rich pickings out in Poyais, quite literally.

Why did people fall for it?

A reported seven boatloads of people made for Honduras. When they finally reached their destination, it was more Buyer’s Remorse than Utopia.

Historic UK writes that passengers found “a vast jungle with only natives for company and the poor and bedraggled passengers of the previous voyage.”

As with many high profile confidence tricks, people wonder how the victims were taken in. Konnikova explores the psychology behind such deceptions. MacGregor is a key case study, regarded as arguably the greatest con in history.

He appears to have approached possible investors from two sides. On the one hand, he was an aggressive alpha, cramming idyllic images into people’s minds. Meanwhile, MacGregor targeted the practicalities as an omega, breaking down the “inertia that prevents them from wanting to do it”.

These tactics are familiar to experts today. Back then, however, they were as mysterious as the Americas themselves. This brings us to another important factor — in a time before Google Maps, people had to rely on what they were told. It was easier to pull the wool over people’s eyes.

No doubt MacGregor possessed that all-important gift of the gab, as they say. He looked like the perfect con man, with marks practically lining up for the taking.

Gregor MacGregor, Scottish champion and Prince of Poyais

Just what was so convincing about him? For starters, this relatively youthful hero of the Latin American military was born in Scotland. Furthermore, he had a family connection to Rob Roy. He played on his identity as he went about fleecing fellow countrymen and others.

Gregor MacGregor had served extensively for Queen and Country. He found himself in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars while still a teenager, as mentioned by Historic UK.

Coverage of MacGregor places him somewhere between a soldier, an adventurer, and a smooth-talking self-publicist. From British pluck to Latin American fire, he appears to have acquitted himself admirably, earning acclaim along the way.

Yet he also had a taste for fantasy. By 1811, he was Sir Gregor MacGregor, married and based in London. Most of that sentence is correct. MacGregor threw in the noble title himself.

Even the passing of his wife — well-to-do Admiral’s daughter Maria Bowater — didn’t halt his momentum. MacGregor’s time in London may have been brief and ultimately tragic. However, Maria’s demise led to him setting sail for warmer climes, after being inspired by Venezuelan revolutionary General Francisco de Miranda.

The dark side of paradise

MacGregor’s tale is an elaborate chronicle of con artistry. He wound up behind bars, though had a habit of evading justice. Once, when brought to court, he got off Scot-free, so to speak. His Poyais plot served him well between 1821-37.

More from us: 5 Crazy Cures Sold By Con Artists

On a less colorful note, those he conned either struggled or, in some cases, died. They paid the price for his financially-fuelled fantasies.

MacGregor passed away in 1845. He was in Caracas, with the fury generated by his underhand empire hot on his heels.