The Battle of Mons took place in Belgium on August 22-23, 1914. Despite being outflanked and heavily outnumbered, the British Expeditionary Forces held off the Germans and retreated to safety.

But when a story about an angel appearing to assist the British soldiers in their hour of need was published in The Evening News, everyone thought it was an actual retelling. The idea of divine intervention lifted the nation’s spirits.

Even when the author explained that it was fiction, people still didn’t believe him, and the legend persists today.

What happened at Mons?

In August 1914, the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF) found themselves outnumbered five to one by advancing Germans as they tried to hold the line at the Mons-Condé Canal. There was no way they could win, so the officers decided to retreat and try to save as many lives as they could.

Even though the BEF were retreating, the soldiers kept fighting furiously. In the end, the Allied soldiers reached safety, and the Germans ended up sustaining more injuries than the BEF.

Although it wasn’t a victory for the British, the fact that so many Allied soldiers escaped while so many Germans were killed made it a big story in Britain.

The story takes shape

When Welsh writer Arthur Machen read some reports of the battle, he was inspired to write a short story called “The Bowmen.” He describes how, one Sunday morning before mass, “I saw the awful account of the retreat from Mons. I no longer recollect the details; but I have not forgotten the impression that was then on my mind. I seemed to see a furnace of torment and death and agony and terror seven times heated, and in the midst of the burning was the British Army.”

In Machen’s story, a desolate band of surviving soldiers is preparing to face death. One of them recalls a plate he once saw in a vegetarian restaurant. It featured Saint George and bore the motto: “May Saint George be a Present Help to the English.” He mutters this under his breath then is astonished to see “a long line of shapes, with a shining about them” appear between the British and the German armies. These shapes turn out to be phantom bowmen from the Battle of Agincourt, summoned by his desperate prayer. The bowmen turn the tide of the battle and secure victory for the British.

Machen chose to write this story from the soldier’s first-person point of view, as if it was an eyewitness account. “The Bowmen” was published in The Evening News on September 29, 1914.

An inadvertent hoax

A peculiar set of circumstances conspired to make people think that Machen’s piece was actually a factual account rather than fiction.

First, “The Bowmen” was not clearly labeled as fiction. Second, the same edition of The Evening News featured another short story published under the heading of “Our Short Story,” which inferred that everything else was fact. Third, Machen employed the “false document” style of writing where the author strives to convince the audience that what they’re reading is fact, not fiction.

With all these elements combined, many people believed that “The Bowman” was an actual account of divine intervention at the Battle of Mons.

People refused to believe Machen when he said the story wasn’t true

Soldiers coming back from the front seemed to corroborate this sensational story. Some historians think that the soldiers might have been hallucinating at a time when they were under tremendous pressure, suffering from extreme exhaustion, and hadn’t eaten for 24 hours. However, others point out that some reports were given by experienced soldiers who would be less likely to suffer such hallucinations. There are also reports that captured German soldiers wanted to know who the golden-haired man on the white horse had been since he seemed impervious to bullets.

Whatever the truth, these stories were being passed far and wide at the end of 1914 and the beginning of 1915. Suddenly, Machen found himself being contacted by people who wanted to reprint his story and cite his original sources.

To try and quash the rumors, he published the story in a new book in 1915 entitled The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War. In his preface, he denies that “The Bowmen” was inspired by hearing of an actual angelic intervention at the battle. He clarifies that “all ages and nations have cherished the thought that spiritual hosts may come to the help of earthly arms” and adds that “Kipling’s story of the ghostly Indian regiment” was also on his mind.

He goes on to describe how the editor of a parish magazine wrote to say the story was so popular he wanted to republish it as a pamphlet. The editor also wanted a short preface with the exact authorities cited. Machen assured the man that the story was complete fiction, but then explains what happened next: “The priest wrote again, suggesting – to my amazement – that I must be mistaken, that the main ‘facts’ of ‘The Bowmen’ must be true, that my share in the matter must surely have been confined to the elaboration and the decoration of a veridical history.”

Machen compares the different versions

In his 1915 preface, Machen details some of the stories he’d heard and how they relate to his work of fiction.

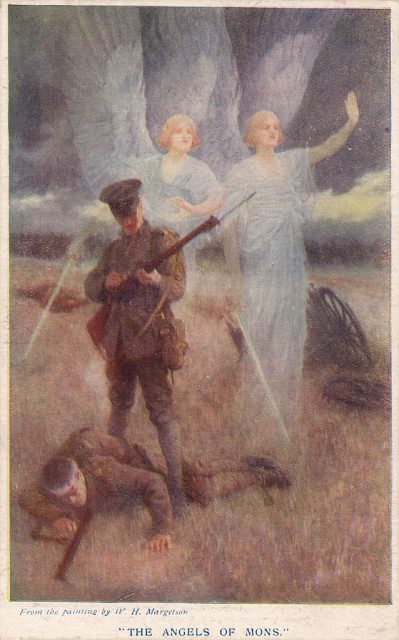

Some of the accounts involved a restaurant with a picture of St. George (clearly a direct link to the story). Others mention a cloud descending, with shining figures that frighten the German horses. He believed that these “shining figures” started out as his fictional bowmen and then were gradually developed into the Angels of Mons.

One version stated that the bodies of the German soldiers had arrow wounds. Machen had actually considered adding such a detail to his own story and rejected the idea. “I was therefore entertained,” he wrote, “when I found that what I had refused as too fantastical for fantasy was accepted in certain occult circles as hard fact.”

He ends up concluding: “if I had failed in the art of letters, I had succeeded, unwittingly, in the art of deceit.”

Even the Society for Psychical Research didn’t believe the stories

The lack of eyewitness accounts of an angelic presence at Mons was a key issue for the Society for Psychical Research (SPR). After investigating the issue in 1915, it concluded that the story was “founded on mere rumour, and cannot be traced to any authoritative source.” With regards to firsthand evidence, it stated: “We have received none at all, and of testimony at second-hand we have none that would justify us in assuming the occurrence of any supernormal phenomenon.”

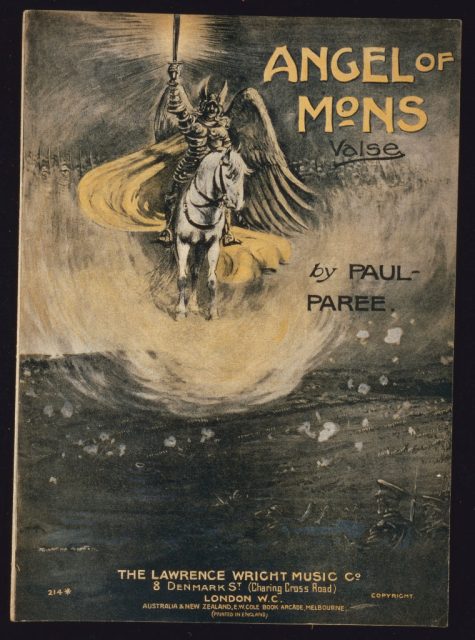

In his memoirs, Brigadier-General John Charteris mentions a rumor that was circulating at the time of an “Angel of the Lord, clad in white raiment, bearing a flaming sword, appearing before the German forces at the Mons battle forbidding their advance.” However, records indicate that Charteris was not at Mons, so this cannot be a firsthand account. In addition, his notes and correspondence from 1914 make no mention of such a rumor, suggesting that he added it in later.

There were some who put forward the argument that the story was part of military propaganda, spread to try and boost morale for the British and feed disinformation to the enemy. Whether this is true is still a matter of debate.

More from us: The Christmas Truce of 1914 – When WWI Enemies Briefly Mingled as Friends

Whatever the truth behind it, the Angel of Mons helped to bolster the enthusiasm of a war-weary population. It has also inspired artists throughout the ages, including Agatha Christie, whose story “The Hound of Death” was partly inspired by this wartime tale.