In our opinion, history is an extremely important subject taught in school. It teaches the next generation about mistakes made in the past, and helps young people learn how to avoid these mistakes in the future. However, many significant world and American events are brushed under the rug and not discussed in the classroom. Here are six major historic events that are not often discussed in schools but deserve their place in the history curriculum.

1. Pope Gregory IX started the Black Plague

Alright, so Pope Gregory IX indirectly started the Black Plague – he didn’t do it on purpose. Pope Gregory hated cats, and because of this vendetta, decreed that black cats were an incarnation of the Devil and called for the complete elimination of them in the first bill of his papacy, the Vox in Rama, published on June 13, 1233.

Because much of Western Europe was Roman Catholic, they followed the Pope’s decree and actually eliminated a lot of cats. However, cats worked essentially as pest control in medieval cities and ate a high number of rats that roamed around these cities. The depletion of cats meant that the number of rats increased. Rats carried fleas, which carried the bubonic plague.

The bubonic plague ended up killing between 25 to 50 100 million people throughout Europe. Scholars believe that the bubonic plague was able to spread so rapidly because Pope Gregory had gotten rid of so many cats, which allowed rats carrying the disease to flourish.

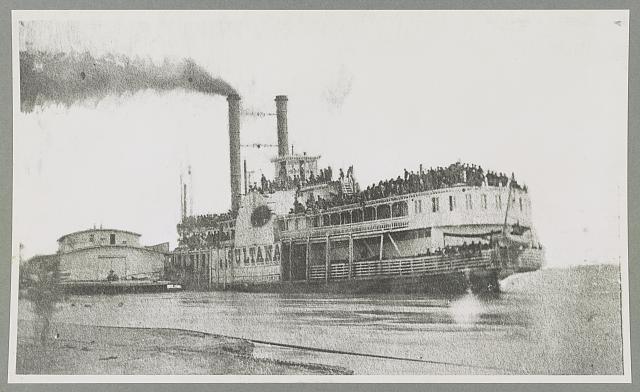

2. The Sultana Explosion

The Sultana Explosion was the deadliest maritime disaster in United States history, yet it is only very rarely discussed in school. The Sultana was first launched in Cincinnati in 1863 and was licensed to carry 376 passengers. During the Civil War, the Sultana made regular trips between New Orleans and St. Louis, transporting troops and supplies for the federal government.

On April 24, 1865, the Sultana stopped in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to pick up discharged Union soldiers – many of them prisoners of war held in Confederate POW camps. The government paid steamboat companies to bring soldiers to their homes in the North, paying $5 for each enlisted man and $10 for each officer. As a result, many steamboat companies took aboard as many soldiers as possible to make the most money.

After its stop in Vicksburg, the Sultana left port with an estimated 2,500 people on board – most of them Union soldiers. Keep in mind that the Sultana was only licensed to carry 376 passengers. On April 27, 1865, three out of the four boilers on the Sultana suddenly exploded, and within minutes the entire boat was engulfed in flames. Around 1,800 people died due to burns from the explosion or drowning after being thrown from the boat.

Although this is the worst naval disaster in American history, it is often overlooked for a number of different reasons. The tragedy was overshadowed by Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 15, 1865. Similarly, the Civil War had ended on April 9, 1865, and the nation was celebrating the end of the war.

3. Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921

One of the worst incidents of racial violence in American history, the Tulsa Race Massacre, is not often discussed in history class. Over the span of 18 hours, from May 31 to June 1, 1921, a white mob attacked homes, businesses, and residents in the predominantly African American Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa, Oklahoma.

On May 31, 1921, a Black teenager named Dick Rowland was accused of assaulting an elevator operator, Sarah Page. By the time Rowland was arrested the next day, rumors had been swirling about the supposed encounter in the elevator. By the evening of the 31st, hundreds of white people gathered around the Tulsa County Courthouse demanding the authorities hand over Dick Rowland, presumably to lynch him.

At around 9 p.m. on the evening of May 31, about 25 African American men, many of them World War I veterans, went down to the courthouse to offer their services to help protect Rowland, but their service was denied, and they returned to their homes in Greenwood. A group of 75 armed Black men returned to the courthouse shortly after 10 p.m. after a rumor was circulated through the Greenwood neighborhood that the whites were storming the courthouse.

Shots were fired at the courthouse, and chaos broke out. Over the next several hours, groups of white Tulsans committed acts of violence against the city’s Black citizens. Some of these white citizens were deputized and had been given weapons by city officials. As dawn broke on June 1, thousands of white Tulsans rioted in the Greenwood District, looting and burning residential homes and businesses over an area of 35 city blocks.

An estimated 1,256 houses were burned, and 215 homes were looted but not destroyed. The Oklahoma Bureau of Vital Statistics officially recorded 36 dead, but some historians estimate the death toll may have been as high as 300 people. Despite the fact that this was a major event not just in Tulsa’s history, but in America’s, the massacre has deliberately been covered up by city officials. In fact, a bill in the Oklahoma State Senate requiring that all Oklahoma high schools teach students about the Tulsa Race Riot failed to pass in 2012.

4. Elizabeth Jennings Graham

Rosa Parks is, thankfully, taught in history class for her role in the Montgomery bus boycott. However, a century before Rosa Parks refused to move to the “colored” section of a bus in Montgomery Alabama, a schoolteacher named Elizabeth Jennings Graham became the first Black woman to ride a whites-only horse-drawn streetcar in 1855.

On July 16, 1854, Graham was waiting for a bus (a horse-drawn carriage) in New York City. Although the city was home to the nation’s largest African-American population in pre-Civil War America, racism was still extremely prevalent.

in 1854, some buses had signs stating “Colored Persons Allowed” signs, while other buses without signs were largely governed by an arbitrary system of passenger choice. When Elizabeth Jennings Graham got on the bus that fateful July day, she had boarded one with no sign in its window. Although slavery had been abolished since 1827, the conductor of the streetcar told Jennings to wait for the next streetcar which “had her people in it.”

Upon hearing this, Jennings demanded to stay on the streetcar, to which the conductor responded “well you may go in, but remember, if the passengers raise any objections you shall go out.” Jennings felt insulted by the conductor so she told him that he was a “good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.” This upset the conductor, who tried to pull her from the car while she clung to the window sash.

The case ended up being brought to court, and eventually, the New York State Supreme Court, Brooklyn Circuit, ruled that African Americans could not be excluded from transit so long as they were “sober, well behaved, and free from disease.” Although total desegregation of public transit took many more years to be enacted, Elizabeth Jennings Graham started something much bigger than herself which would come full circle one hundred years later.

5. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

The Triangle shirtwaist factory fire is often remembered as one of the most famous incidents in American industrial history, and yet it is rarely discussed in school. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory employed young immigrant women who were forced to work in extremely close quarters. These women, who were nearly all teenaged girls, worked 12 hours a day every single day. The women working in this factory were only paid $15 a week despite working such long hours each day.

On March 25, 1911, 600 women were working in the factory when a fire began in a rag bin. A fire hose was used in an attempt to distinguish the initial blaze, but the hose was rotted and the valve rusted shut. Within 18 minutes, a total of 146 people had perished in the fire.

Despite the tragedy of the fire, it helped unite and organize labor and reform-minded politicians. The workers union set up a march on April 5, which was attended by 80,000 people to protest the labor conditions that had led to the fire in the first place.

6. The Bombing of Wall Street

Eighty years before the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, New York was victim to another heinous attack. During the lunchtime rush on September 16, 1920, a horse-drawn wagon was parked in front of the U.S. Assay Office, across from the J.P. Morgan building, on the busiest corner of New York City’s financial district. Moments later, the cart exploded in a timer-set detonation, sending shrapnel and debris through the air.

More from us: Claudette Colvin was the first person to resist bus segregation in Alabama

Thirty people were killed immediately and 300 others were severely injured. The next day, despite the bombing that occurred, it was business as usual on Wall Street. However, no one ever took the blame for this terrorist attack and the 1920 bombing of Wall Street remains unanswered today. It is theorized that followers of the Italian Anarchist Luigi Galleani could potentially be responsible for this event, but it has never been proven.