Thanks to the bestselling book by Dan Simmons and the AMC drama anthology television series, HMS Terror is now one of the most famous ships in the world.

What happened to the vessel and its crew still remains a mystery, but when the AMC series made it onto British screens earlier this year it encouraged curators at the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) to take another look at their collections and what the recovered relics can tell us about life aboard ship in the Arctic.

Starting out

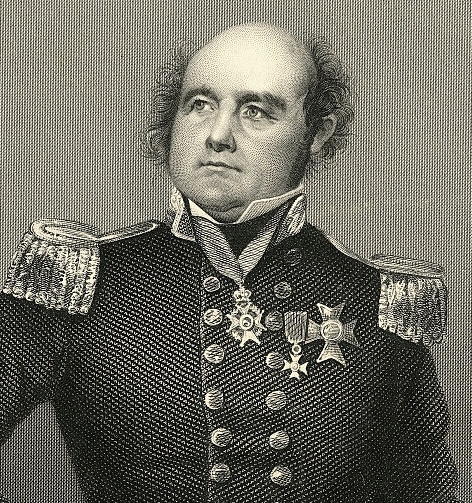

HMS Terror and HMS Erebus must have seemed like the perfect ships to locate the Northwest Passage. Terror had actually been in polar seas twice before she came under the command of Captain Crozier.

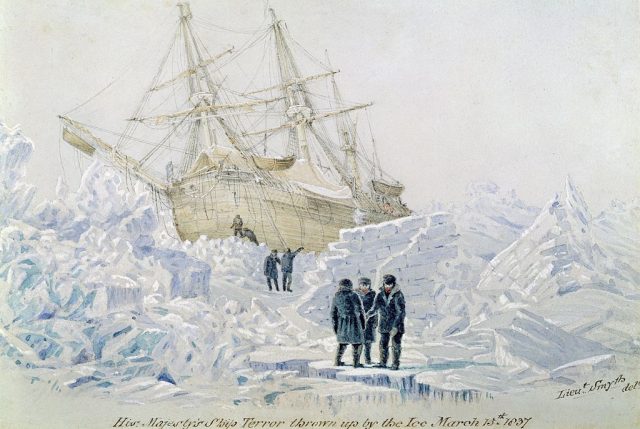

In 1836, under the command of Captain George Back, Terror went to Hudson Bay. After being caught in the sea ice for ten months, she finally returned to port.

A more successful expedition took place in 1840, under James Clark Ross. Both Terror and Erebus took a three-year trip around Antarctica.

The final journey of both ships began in May 1845. In August of that year, they were spotted at Baffin Bay, after which they were never heard from again.

Several rescue missions were sent out, but there was no sign of the crew or the ships.

The Victory Point note

Although it doesn’t tell us everything about what happened, a note discovered on King William Island in 1859 gives some clue as to what happened after Baffin Bay.

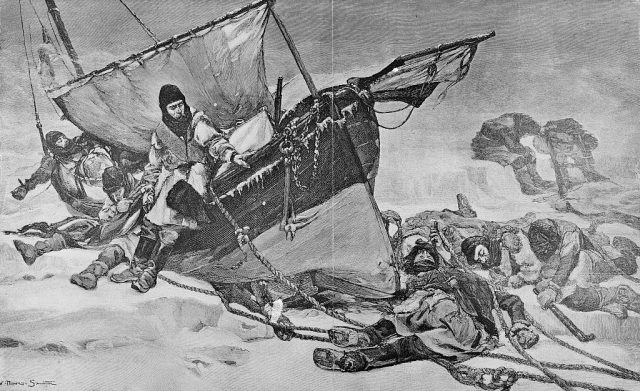

The note is dated April 1848 and reports that both ships were trapped in ice in Victoria Strait, forcing the crews to abandon ship. The men began a long trek toward a fur-trading post around 600 miles away but never made it.

Today, the note is held by the RMG, and it’s possible to view a video about it on their website. The paper is a standard Admiralty form that has the following message printed on it in several different languages:

“Whoever finds this paper is requested to forward it to the Secretary of the Admiralty, London, with a note of the time and place at which it was found: or, if more convenient, to deliver it for that purpose to the British Consul at the nearest Port.”

The crucial information on the Franklin expedition is handwritten in the margins, giving details of the abandonment and stating that the ships had been stuck in the ice since September 1846. It also mentioned that Sir John Franklin died on June 11, 1847, although no further details are given.

What was life like onboard?

When they were being fitted out, both Terror and Erebus had coal boilers installed. These served two purposes. Firstly, the extra power would allow them to charge through the icy seas much faster than just sails or oars; secondly, the heat from the boilers would keep the crew nice and warm.

This was considered a huge bonus because the men would be constantly fighting the cold. Even their own bodies worked against them. If they worked up a sweat during their duties, their sweat would freeze to ice inside their clothes once they stopped. According to the RMG: “even taking a balaclava off could rip the skin and beard from the chin.”

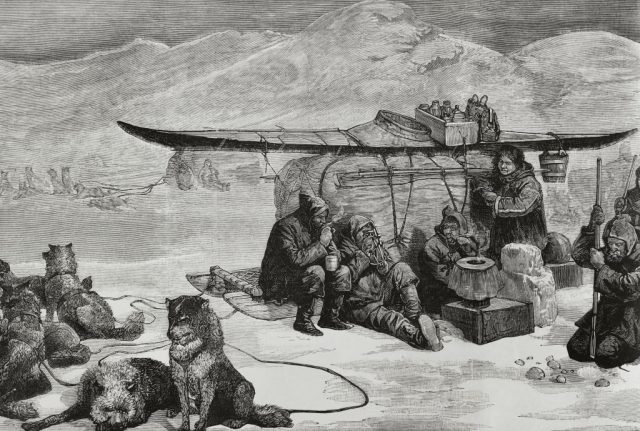

The back of beyond

Previous Arctic expeditions had made contact with local Inuit tribes, who would help supply them with clothing, oil, and meat ”“ the single most important thing to help fight off scurvy. Seamen were given a daily ration of lemon or lime juice to try and save them from the debilitating effects of scurvy, but as time wore on, the potency of the citrus juice would reduce, and the deadly disease would start to take hold. Fresh meat from friendly Inuit tribesmen could provide them with much-needed vitamin C.

However, as Claire Warrior, Senior Exhibitions Curator, states: “Franklin’s ship was trapped in the ice in a remote and desolate area, which Inuit rarely visited, calling it Tununiq, ”˜the back of beyond.’” There was little chance that local Inuits would be able to help out the crews of Erebus and Terror.

But Franklin had planned for this eventuality and had stocked both ships with enough food for three years.

Unfortunately, there was an unseen and deadly flaw in his plan.

Poisoned by their own food

Relics found in the years since include tin cans, cutlery, and snow goggles. There were also some human remains found on King William Island. In 1981, Dr. Owen Beattie used modern forensic techniques to see if he could identify the remains and figure out what killed them.

Dr. Beattie’s investigations revealed a startling amount of lead in the bones of the men. This gave rise to the theory that some men had been poisoned. But where did all that lead come from?

Further investigations exhumed some particularly well-preserved crewmen from Beechey Island. When examined by Dr. Beattie’s team, they came to the conclusion that they must have been poisoned by their own food. The cans had been improperly soldered with lead that had then leeched into the food.

Marks on some skeletons found suggest that some crew members resorted to cannibalism in the face of starvation and as an alternative to food that was slowly poisoning them.

What did the sailors do all day on the ice?

With heated ships and temperatures outside dropping as low as -48 degrees Celsius overnight, it must have been tempting for the men to huddle inside in the warmth. But everyone had duties to perform. Those not given over entirely to making the ship run (checking the rigging, cooking the food) would have had to make magnetic and meteorological observations.

However, as the RMG warns, even simple observations could be dangerous: “Placing cold metal instruments to the eye could cause the skin to be damaged or even removed, and the men had to hold their breath to stop condensation forming on the glass parts.”

Frostbite was a common affliction. Men could even get sores on their face if mucus ran from their nose and then froze there. Hypothermia was as much of a constant threat as scurvy.

There was also a monkey onboard

To ensure a supply of fresh meat early on in the voyage, both ships would have had cattle, sheep, pigs, and hens. However, Erebus also carried three pets. There was a Newfoundland dog called Neptune who was very popular with the crew, a cat kept for catching rats, and a little monkey that was a gift from Sir John’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin.

When Erebus and Terror set sail, they had 129 men aboard. By the time Captain Crozier ordered the abandonment of the ships, there were only 105 men still alive. Many of them would have been weak from a combination of extreme hunger, frostbite, and scurvy.

A past almost perfectly preserved

In 2014, the wreck of Erebus was found off the coast of King William Island. Two years later, the sunken Terror was located in Terror Bay, about 45 miles away from Erebus‘s final resting place.

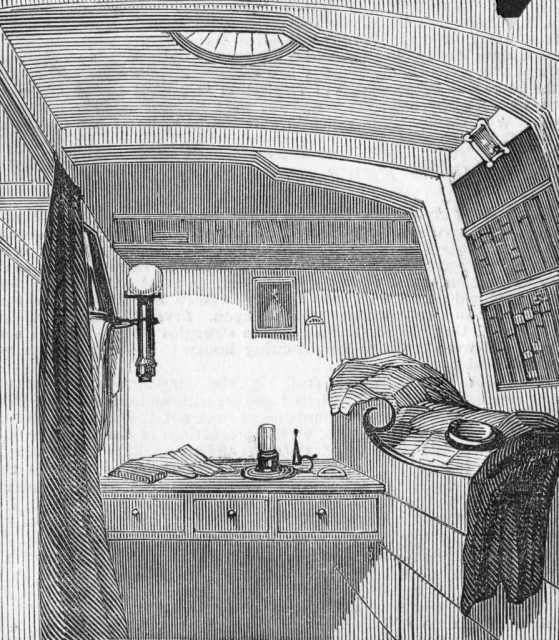

It wasn’t until 2019, when technology was sufficiently advanced, that these wrecks could be properly investigated. What the ROVs (remotely operated vehicles) found was furniture still in place and even paper maps that were in a readable state. In the captain’s cabin there were maps, a tripod, several thermometers, and cabinets with plates and cutlery, many still retaining their color.

The lack of decomposition was thanks to the zero-degree water temperature, a lack of natural light, and sedimentation. All of those elements combined created an environment that preserved rather than destroyed.

More from us: “Frozen in Time” Arctic Shipwreck of HMS Terror ”“ See how it Looks Today

ROV pilot Ryan Harris is reported by Curiosity Well as saying: “The impression we witnessed when exploring the HMS Terror is of a ship only recently deserted by its crew.”

It’s hoped that such well-preserved items might provide answers in the future as to what happened to the ships in the past.