Ask someone to name some famous medieval monarchs, and you’ll get the likes of William the Conqueror, Richard the Lionheart, and Edward the Confessor.

But there are some fabulous queens too who deserve to be remembered just as much as their male counterparts.

Here are six of the best medieval queens rarely mentioned in history lessons.

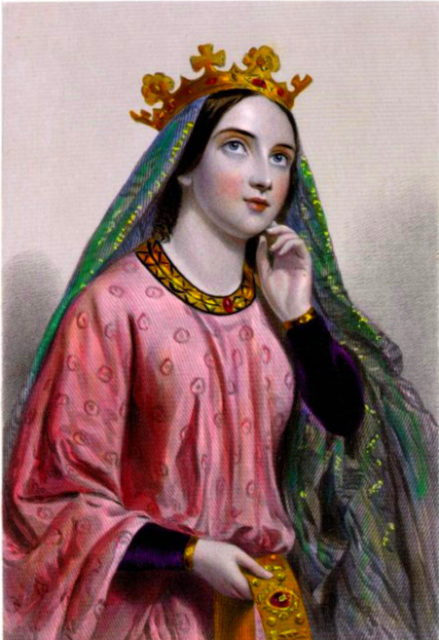

Margaret of Anjou

When Margaret married King Henry VI in April 1445, she couldn’t have known that part of her queenly duties would be ruling England in his place during bouts of insanity.

It was during one of these bouts, in May 1455, that Margaret called a Great Council, deliberately excluding Richard of York and his faction. It’s believed that this is one of the factors that brought about the 30-year-long Wars of the Roses.

Margaret stood out as a fierce leader in a world of men, leading the Duke of Suffolk to praise “her valiant courage and undaunted spirit.”

She became a key player in the Wars of the Roses and a leader of the Lancastrian cause. She headed her own army at the Battle of Tewkesbury in May 1471, but was defeated and captured. As she was his cousin, King Louis XI of France provided the ransom for her – although not until 1475.

For the next seven years, this great woman was reduced to living in France as a poor relation of the king.

Berengaria of Navarre

Known as “the only English queen never to set foot in the country,” Berengaria showed her affection for her husband, Richard the Lionheart, in different ways than other women – such as accompanying him on a crusade.

Richard had previously been engaged to Alys, a half-sister of King Phillip II of France. However, when it turned out that Alys might have been his father’s mistress and mother of an illegitimate child, Richard decided not to go ahead with the marriage.

His mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine (more on her below), brought Berengaria to Richard while he was away on the Third Crusade. They were married on May 12, 1191, in Cyprus, and then they set out to continue the crusade together.

Berengaria returned from the Holy Land before Richard did – which is just as well since he was captured when he finally returned to Europe. Berengaria was one of those who helped to raise money for his ransom.

Although she never visited England as queen, she might have gone there after Richard’s death – if only to try and secure the pension she was owed as dowager queen that King John did not pay.

Historian Ann Trindade describes Berengaria as “a strong, courageous woman, independent, solitary, battling against difficult political and economic circumstances.”

Queen Philippa of Hainault

Being the mother of Edward, the Black Prince, is not Philippa’s only claim to fame. In 1346, she acted as regent for her husband Edward III while he was away in the Hundred Years’ War.

Most impressively, during her regency, she managed to put together an English army to fight the Scots at the Battle of Neville’s Cross. From horseback, she rallied her soldiers so that they forged ahead to an English victory.

With the country in financial difficulties due to the war, Philippa encouraged Edward to take an interest in the country’s commercial expansion to try and claw back some of the money spent.

Philippa was known for her compassion, something that made her popular with the common people. She is particularly remembered for convincing Edward II to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais when the town was captured after a siege; Edward had planned to execute them as a message to the townspeople, but he stayed his hand on Philippa’s advice.

Eleanor of Aquitaine

Eleanor got engaged to the Duke of Normandy after her 15-year marriage to King Louis VII of France was annulled due to the lack of a son and heir. When the duke was crowned King Henry II of England in 1154, it meant that Eleanor had been a queen of both France and England.

Being the Duchess of Aquitaine in her own right, Eleanor chose to take the cross as part of the Second Crusade alongside her first husband.

After becoming somewhat estranged from her second husband, Eleanor lived in Poitiers from 1168 to 1173. Her son, Henry, visited her there in the 1170s, and they encouraged his younger brothers – Richard and Geoffrey – to support Henry in deposing his father, King Henry II.

As a result of her involvement, Henry II imprisoned Eleanor from 1173 to 1189. Before young Henry died of dysentery in 1183, he begged his father to forgive Eleanor for supporting him, and so Eleanor was allowed a little freedom.

When Henry II died in July 1189, Eleanor’s son Richard became King Richard I. While Richard was engaged in the Third Crusade, Eleanor ruled England in his name, signing documents: “Eleanor, by the grace of God, Queen of England.”

This fierce queen hasn’t been completely forgotten by history, and Eleanor has appeared in various books and films. In the 1968 movie The Lion in Winter, Katharine Hepburn played Eleanor and won an Academy Award for Best Actress.

Brunhilda of Austrasia and Queen Consort Fredegund

The name “Brunhilda” is inextricably linked with the Valkyrie in the Völsunga saga and Richard Wagner’s opera Der Ring des Nibelungen. If you’re of a certain generation, you might even associate the name with Bugs Bunny wearing a helmet, fake plaits, and riding a fat horse.

However, the real-life Brunhilda and her life-long nemesis Queen Fredegund were powerful women in medieval times.

According to an in-depth article by Shelley Puhak for the Smithsonian Magazine, these two women “were dismissed as minor queens of a minor era.”

Brunhilda married King Sigibert. In an effort to upstage his older sibling, Sigibert’s brother Chilperic decided to marry Brunhilda’s sister, Galswintha.

But sometime after Galswintha discovered Chilperic in bed with a royal servant named Fredegund, the queen was found strangled in her bed. Chilperic made no effort to find his wife’s assassin and simply married Fredegund.

Claiming that Galswintha’s lands now belonged to her sister, Sigibert invaded Chilperic’s realm. Fredegund hired two assassins to kill Sigibert while he was besieging her husband at Tournai. Grateful to his clever wife, Chilperic made her his chief adviser.

Brunhilda became regent on behalf of her son Childebert II. Instead of fighting, she chose to work on the nation’s infrastructure – repairing roads and building fortresses and abbeys.

When Chilperic died (rumored to have been killed by Brunhilda), Fredegund became regent for her son Chlothar II. She was a fighter, and she took a commanding role at the head of her armies.

One story relates how Fredegund took one of Brunhilda’s camps by surprise, getting her men to march at night with foot soldiers at the front holding up tree branches to obscure the silhouettes of the mounted riders behind.

Brunhilda met a rather unpleasant end in 613 when Chlothar II had her executed by being pulled apart by four horses. Fredegund was already dead by then, having passed away due to natural causes in December 597.

More from us: Madame de Pompadour – Kings and Courtiers were in the Palm of her Hand

Brunhilda was queen for 46 years (acting as regent for 17 of those years), and Fredegund was queen for 29 years (regent for 12 years). According to Puhak, this means that “both ruled longer than almost every king and Roman emperor who had preceded them.”