After Lady Diana Spencer married Prince Charles in 1981, she became known as “the people’s princess” due to her beauty, grace, style, and generosity.

But Diana wasn’t the first woman to be named “the people’s princess.” Over a hundred years before Diana was born, Princess Charlotte of Wales had captured the hearts of her people. Like Diana, she also cast the nation into mourning with her sudden and untimely death at the age of 21 years old.

A marriage made in hell

When George, the Prince of Wales, married Caroline of Brunswick in April 1795, it was clear from the outset that they were not compatible. Although they lived under the same roof, they were effectively separated, and Prince George later claimed they only had sexual relations three times. But that was enough to secure them one child: Charlotte Augusta, born on January 7, 1796.

King George III was delighted with this event, hoping that the baby would bring his son and daughter-in-law together again. It didn’t. Three days after Charlotte was born, Prince George changed his will to declare that Caroline could have no role in bringing up Charlotte. Twisting the knife further, he left all his goods to his mistress, Maria Fitzherbert.

With no chance of a reconciliation, it looked like Princess Charlotte would be sure to inherit the throne after her father’s death. Everyone saw her as the future of the nation, a beloved princess who stood in stark contrast to the madness of her grandfather and the debauchery of her father.

A lonely life but a royal education

Caroline left Carlton House in August 1798. Charlotte was moved out of the house to make space for her father’s mistress and was given her own household. The princess and her retinue moved around, spending time at Shrewsbury House then Lower Lodge in Windsor before settling in Warwick House.

With neither parent particularly interested in raising their daughter, a number of governesses were taken on. One of them, Lady de Clifford, was too softhearted to discipline the young princess, meaning that Charlotte grew up quite headstrong.

Lady de Clifford also brought one of her grandsons, the Honorable George Keppel, to be Charlotte’s playmate. Their antics encouraged her rebellious, tomboy nature. Keppel grew up to become the Earl of Albemarle, and his memoirs contain anecdotes of their childhood antics.

Since Charlotte was the King’s only grandchild, he arranged her education himself. Her tutors instructed her in history, French, English, and Latin. The Bishop of Exeter was retained to provide religious instruction. She also had dancing and horse-riding lessons, and the Prince Regent was said to have been proud of her skills as a horsewoman.

Conflicting views about her relationship with her parents

Charlotte was also fond of poetry and compiled a book of favorite poems, which is now held by the Royal Collection Trust, along with numerous letters to, from, or about her. From these letters, we get an idea of how headstrong young Charlotte could be. When Lady Elgin writes about confiscating a watch, she describes how: “the fire was kindled- The storm was violent- [the Princess] declaring her poor governess very cruel.”

Other letters show how infrequently Prince George visited his daughter, but they also demonstrate how sorry he was about that fact. Charlotte’s own letters display a desire to please her father and seek his approval, which seems at odds with other historical sources that indicate the princess and the Prince Regent were not close.

One source reported that Charlotte was outraged when her father did not recall the Whigs to office after being made Prince Regent in February 1811. To show her support for the party, she blew a kiss to its leader, Earl Grey, when she attended the opera.

When it comes to Charlotte and Caroline’s relationship, it seems that there was both hostility and affection there. Tracy Boorman, author of Crown & Sceptre: A New History of the British Monarchy from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II, quoted Charlotte in an article for History Extra: “My mother was wicked, but she would not have turned so wicked had not my father been much more wicked still.”

However, it was clear that Charlotte was fond of her mother and distraught when her father insisted they should not meet.

Questions of marriage arise

Once Prince George was made regent, he imposed strict living conditions on his daughter. She spent most of the time with maiden aunts at Windsor, and her clothing allowance was far below what was needed for a princess.

The time spent with her mother allowed Charlotte more freedom. When she fell for Lieutenant Charles Hesse of the Light Dragoons, Caroline would pass notes between them and even allowed the couple to meet secretly in her rooms.

In 1813, the Prince Regent began to consider Charlotte’s marriage prospects. Prince George favored William, Hereditary Prince of Orange. However, after meeting William at her father’s birthday party where both princes proceeded to get drunk, Charlotte was not impressed.

Although she softened a little following a later meeting, a sticking point in negotiations was that Charlotte insisted she would not leave England for long periods once she was queen – something she might need to do since her husband would eventually inherit the Dutch throne. According to Charlotte and Leopold by James Chambers, the princess declared that if William wanted to go to his homeland at any point, he would have to “visit his frogs solo.”

Despite her reservations, Charlotte eventually signed the marriage contract. But the agreement was not to last when her heart was stolen by another man.

Her rebellious nature secures her a place in the nation’s heart

While the Prince Regent was delighted with this engagement, Caroline was very unhappy with the match. By that time, Charlotte was cultivating friendships with three other men: Prussian princes Augustus and Frederick, as well as Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg Saalfeld.

Perhaps as a ploy to end her unwanted engagement, Charlotte insisted to William that her mother must be welcome in their home after their marriage. The Prince of Orange refused, knowing the Prince Regent would not approve such a concession, and Charlotte broke off the engagement.

The Prince Regent was, indeed, outraged and insisted Charlotte be moved to Cranbourn Lodge at Windsor where no one but the Queen could visit her. Charlotte fled her home at Warwick House and made it to her mother’s house where she summoned Whig politicians to advise her. Based on their advice, she voluntarily returned to her father’s house the next day, but her flight and her predicament provoked great sympathy among the public. She was also praised for not wanting to marry a foreigner and abandon her homeland.

In August 1814, when Charlotte was finally permitted some freedom, she visited Weymouth for her health. Huge crowds turned out to cheer her coach and in Weymouth itself was a spectacular illumination with a centerpiece declaring: “Hail Princess Charlotte, Europe’s Hope and Britain’s Glory.”

Marriage to the husband of her choice

When it became clear that marriage to a Prussian prince was off the cards, Charlotte decided that Prince Leopold was the man for her.

Although the Prince Regent was at first against Leopold, everyone else in the family supported the match, and Prince George was eventually won over. After meeting Leopold at a dinner, the Prince Regent even went so far as to say that Leopold “had every qualification to make a woman happy.”

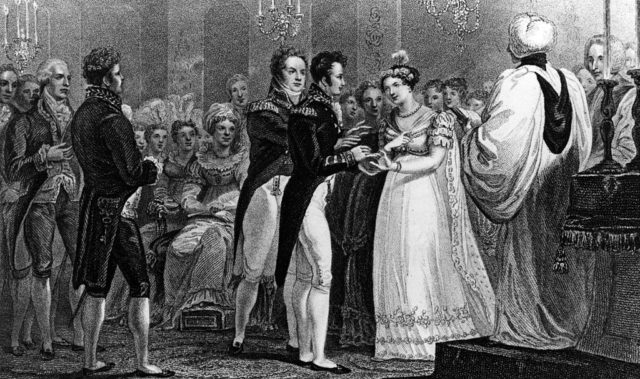

The wedding went ahead on May 2, 1816. Charlotte, with her usual rebellious streak, giggled at the point when Leopold (who was far from wealthy) said he would endow her with all his worldly goods.

A promising pregnancy with a tragic end

The couple were immensely popular and became known as the Coburgs. When they attended the theatre, they would be applauded upon arrival.

During one opera visit, Charlotte took ill, and it was later confirmed she’d suffered a miscarriage. By April 1817, she was pregnant again with every sign that she would carry the baby full term. But the child would be the death of her.

Looking back on Charlotte’s pregnancy and birthing procedures with a modern eye, it’s easy to see what might have been done differently to save the princess and her son.

During the first part of her pregnancy, she didn’t do much exercise or overexert herself, and she had a healthy appetite. However, worried that eating might produce a large child, her medical team put her on a diet from August 1817 onwards. They also routinely bled her, which naturally weakened her over time.

The child was due on October 19, but Charlotte’s contractions didn’t start until November 3. At that point, she was encouraged to exercise but not to eat. It took another two days before Charlotte was able to deliver the child. During this lengthy labor, an obstetrician was sent for but not allowed to see his patient and, crucially, forceps were not used, something which might have hastened the labor and saved both mother and child.

Eventually, Charlotte delivered a stillborn boy on November 5. She was now allowed to eat but after midnight she began vomiting, struggled to breathe, had pains in her abdomen, was cold to the touch, and was bleeding. She died in the early hours of November 6.

The man in charge of Charlotte’s pregnancy and birth was physician Sir Richard Croft. After this tragedy, many of the public blamed him for her death. Three months later, when attending another young woman, Croft shot himself, creating a “triple obstetric tragedy.”

A nation plunged into mourning

The public had been so interested in and excited for Charlotte’s pregnancy that betting shops were taking odds as to what sex the child would be. When news of Charlotte’s death spread, the kingdom went into deep mourning. According to Henry Brougham, a future Whig Lord Chancellor: “It really was as though every household throughout Great Britain had lost a favourite child.”

The shops, the Royal Exchange, the Law Courts, and even the docks all shut down for two weeks. Everyone, including the poor and homeless, tied black armbands on their clothes. So great was the shutdown that some manufacturers of ribbons and other goods not allowed during mourning were afraid they’d be bankrupted and petitioned the government to put an end to the shutdown.

Caroline fainted when she heard the news that her daughter had died. The Prince Regent was so grief-stricken he couldn’t attend Charlotte’s funeral, which took place on November 19, 1817. Charlotte, with her son laid at her feet, was buried in St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle.

Leopold was a broken man. In a letter to Sir Thomas Lawrence, he wrote: “Two generations gone. Gone in a moment! I have felt for myself, but I have also felt for the Prince Regent. My Charlotte is gone from the country – it has lost her. She was a good, she was an admirable woman. None could know my Charlotte as I did know her! It was my study, my duty, to know her character, but it was my delight!”

Princess Charlotte is replaced by Princess Victoria

With the loss of Charlotte – the only legitimate heir – the nation was in turmoil. Who would inherit the throne? Newspapers ran articles that urged the other sons of King George III to marry since it seemed impossible that the Prince Regent would father another child.

The King’s fourth son, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, read one such article, and he was moved to propose to Victoria, Dowager Princess of Leiningen and also Leopold’s sister. He was 50 years old at the time of their marriage, but their union nevertheless managed to produce a daughter: Alexandrina Victoria.

More from us: Queen Victoria And How A Mistranslation Led To A Royal Marriage Proposal

It was this princess Victoria who would become Queen Victoria in 1837, ruling over Britain and Ireland for 63 years.