Dogs first came to the Americas nearly 16,000 years ago during the last Ice Age. These dogs remained on the continent for thousands of years until they suddenly disappeared from the historical narrative. In their place stood European canine breeds. So what happened to all the indigenous dogs that had been in America for so long? A pair of jawbones recently found beneath Virginia’s colonial Jamestown settlement suggests that the starving colonists might have eaten them.

The first dogs in the Americas were thought to be decedents of the wolf that gradually became domesticated. However, these original canines were gradually replaced by European breeds of dogs. Today, Alaskan Malamutes and Siberian Huskies are thought to be the only breeds that retain a genetic connection to their ancient ancestors.

In the 15th Century, the Spanish conquistadors who arrived in the Americas brought large war dogs with them. Other European settlers brought large working dogs over, including bloodhounds and greyhounds, and large hunting dogs.

In 2007 and 2010, two dog jawbones were unearthed at the Jamestown settlement. Ariane Thomas, a University of Iowa graduate student in anthropology, turned to these remains to figure out what happened to all the indigenous dogs in the Americas.

Thomas managed to extract the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the jawbones and then compared it to that of modern and ancient dogs found around the world. She discovered that the dogs’ maternal lines were completely unrelated to European breeds. In fact, the remains of the animals seemed to be most closely related to other ancient dogs from Illinois and Ohio. The remains also seemed to be distinctly related to several ancient arctic dogs.

Interestingly, the dogs found at Jamestown are not closely related to canines found at the Weyanoke colonial village, which was only about 50 kilometers away from Jamestown. This finding suggests to Ariane Thomas that “there’s a lot more diversity than we initially thought.” This discovery suggests that European dogs replaced indigenous breeds much more slowly than initially thought.

The canine remains found at Jamestown feature narrow, shallow cuts, which might suggest these animals were butchered. Some canine remains found dated to around 1620, while others that were found dated to the colonists’ first winter in Virginia. The remains were found among other food waste, including mussel shells and fish bones, which further suggests these dogs were eaten – and that eating canines perhaps wasn’t so uncommon at the time.

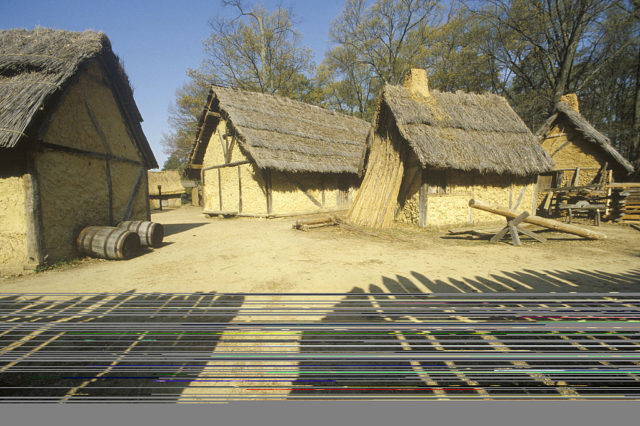

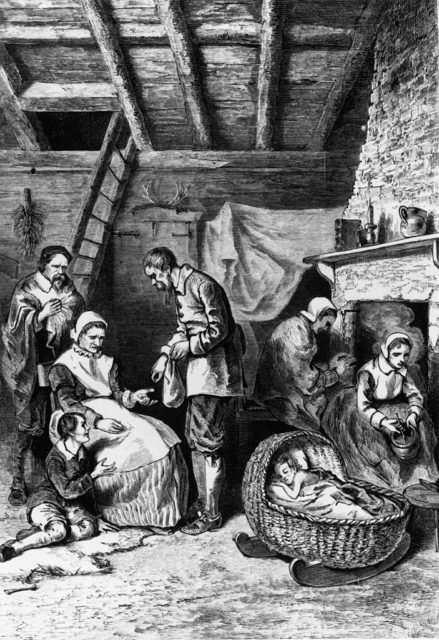

One of the jawbones was discovered beneath a former bakery and the other inside a well that was believed to belong to colonial Governor John Smith. The jawbone uncovered from Smith’s well dates back to 1609-1610. This time period is also historically known as “The Starving Time“‘ for Jamestown settlers. During this time, the settlers – who had little farming experience – faced food shortages, forcing them to resort to drastic measures to avoid starvation.

In 1625, George Percy, who was president of Jamestown during the Starving Time, recalled what the colonists ate during this period: “Haveinge fedd upon our horses and other beastes as longe as they Lasted, we weare gladd to make shifte with vermin as doggs, Catts, Ratts and myce… as to eate Bootes shoes or any other leather.”

The evidence suggests that Jamestown colonists had no other choice but to eat dogs when times got tough for them. What remains a mystery is how these indigenous dogs came to Jamestown in the first place. Perhaps the dogs had Native American owners – the local Powhatans lived very close to the Jamestown settlement.

More from us: 17 Colonial-Era Items That Modern Americans Would Have No Idea How To Use

Ariane Thomas hopes to further look into the jawbones’ DNA to figure out whether the remains came from fully indigenous canines or whether they were a mix of European-indigenous dogs. By examining Jamestown’s history through the dogs, we can learn more about the broader history surrounding the colonists and indigenous societies in the area.