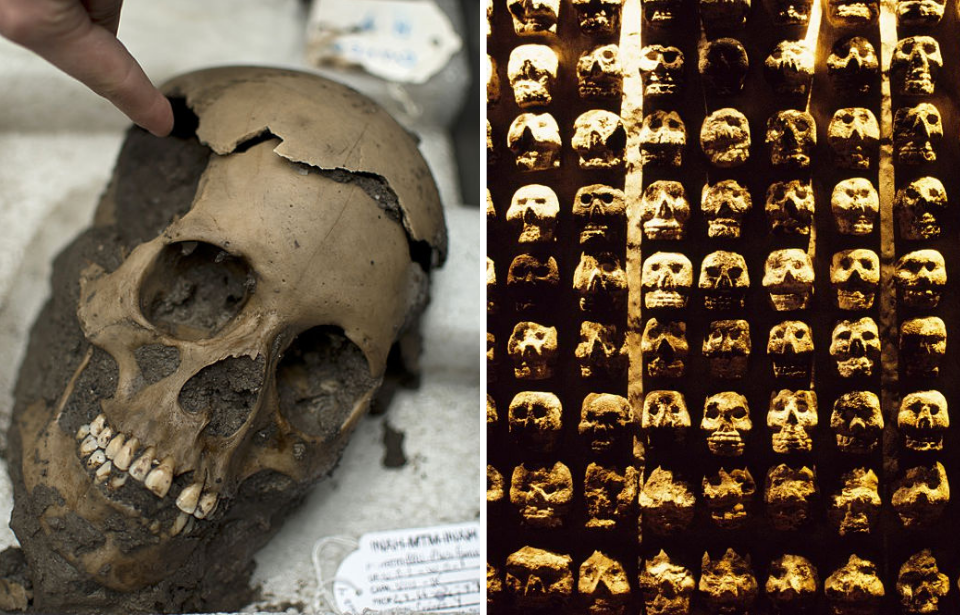

When Mexican authorities found a pile of 150 skulls in a cave near the Guatemalan border in 2012, they thought they were looking at a massive crime scene. Turns out the authorities weren’t completely wrong. They might have been looking at a massive crime scene, but from way earlier than they were initially thinking.

The remains were brought to the Mexican state capital. Over the next decade, numerous tests and analyses were run on these skulls. Experts recently determined that the skulls came from sacrificial victims killed between 900 to 1200 C.E.

The police weren’t incorrect to believe they were looking at a modern-day crime scene when they stumbled upon these skulls. The border area between Mexico and Guatemala has, sadly, seen a rise in violence and immigrant trafficking in the last few decades.

Furthermore, pre-Hispanic skull piles in Mexico tend to have holes through each side of the skull and are usually found in ancient ceremonial plazas.

(Photo Credit: Daniel Cardenas/ Anadolu Agency/ Getty Images)

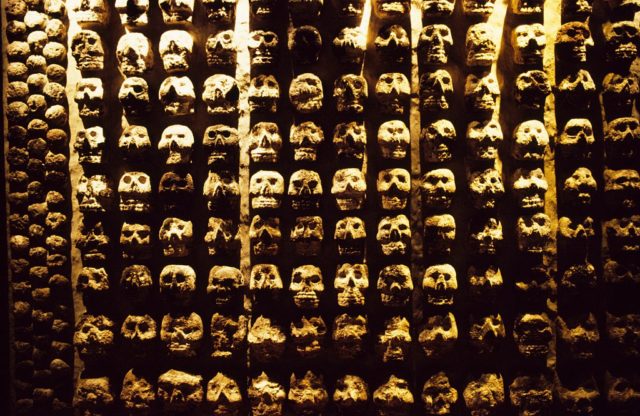

Experts believe the victims found in the cave were probably victims of a ritual decapitation. Their skulls may have been put on a trophy rack known as a “Tzompantli.” Spanish conquistadors including Hernán Cortés, Bernal Díaz del Castillo, and Andrés de Tapia have described Tzompantli skull racks in writings about their conquests. It wasn’t uncommon to see a Spaniard’s head included on a Tzompantli.

However, experts note that these skulls might have rested atop poles rather than being strung on them. In ancient cultures including the Aztecs, Tzompantli racks were typically created by casting a hole through the skull and stringing it up on wooden poles.

More from us: 2,000-Year-Old Skull Shows Evidence of Ancient Surgery

Experts also noted that there were more females than males among the victims found in the cave, and none of them had any teeth. Previously, researchers had thought that skulls in a Tzompantli structure tended to belong to defeated male warriors, but recent analysis has indicated that this is not always the case.

In light of this discovery, archeologist Javier Montes de Paz believes that people should probably call an archeologist before the police.

“When people find something that could in an archeological context, don’t touch it and notify local authorities or directly the [National Institute of Anthropology and History],” he advises.