On February 25, 1919, Margaret Hennessey and her sister were walking to a market when they were approached by officers. The police told them they were under arrest as “suspicious characters” and were taken to a hospital where they were forcibly examined for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). These women were detained off the streets under a new program that had been rolled out across America.

They were not the only ones to experience this as tens of thousands of women, possibly more, were approached, detained, and forcibly examined for the crime of maybe carrying an STI.

A new program

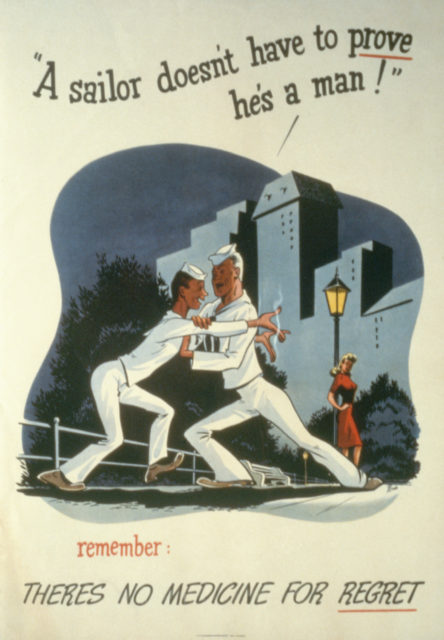

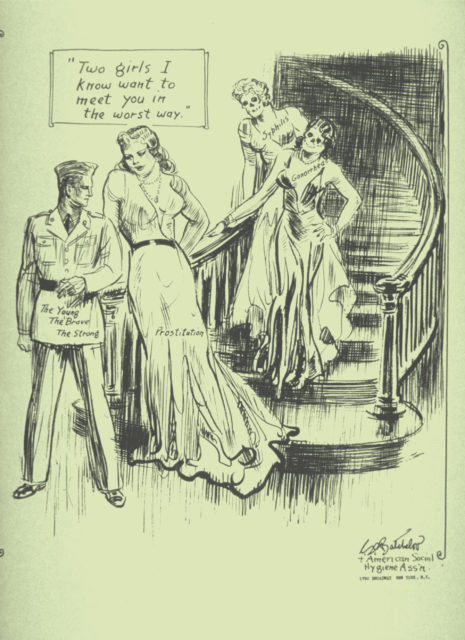

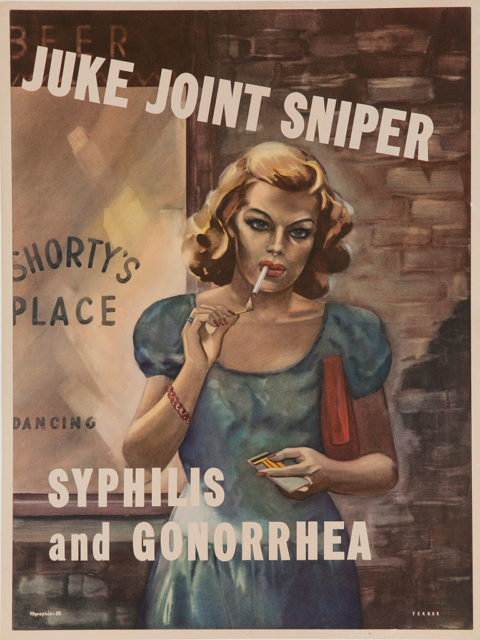

During WWI, a new endeavor called the American Plan was created to try and prevent soldiers and sailors from contracting STIs. At this time, the federal government was shocked to hear that over 100,000 military men were infected with gonorrhea or syphilis, and so they enacted the Plan, outlawing sex work within a five-mile zone of military training camps.

This had minimal effect, as it was discovered that most of the men infected with STIs actually contracted their illness in their hometowns. The federal government responded to this finding by expanding the outlawing of sex work to extend across the entire nation. It was then found that many of the women who supposedly infected these men with STIs were not even prostitutes, and the federal government felt forced to expand the program even further.

Under reasonable suspicion

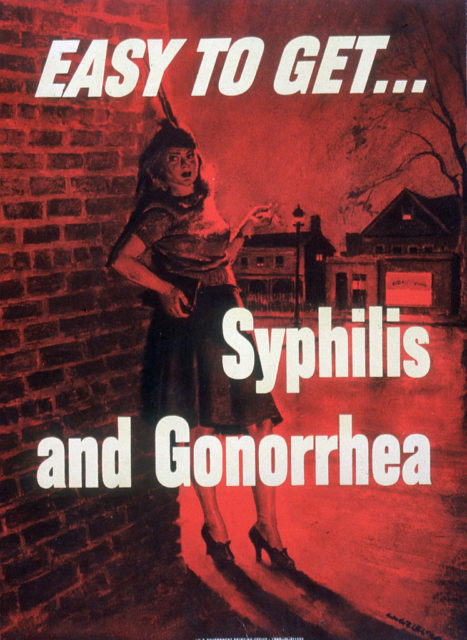

Beginning in 1918, the federal government began pushing a law that granted officials the ability to forcibly examine any person “reasonably suspected” of having an STI. If someone were to test positive, they could be held in detention for as long as it took to render them “cleansed.” In theory, this law was gender-neutral, but in practice, it almost exclusively focused on and targeted women.

The American Plan received a shocking amount of support, including praise from former New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and John D. Rockefeller, who bankrolled the program for decades. They ignored the mass incarceration of women across the country with the belief that the program protected at-risk young women and emphasized the importance of sex education and transparency about STIs.

The “Sacramento Sweep”

On the same day they arrested Margaret Hennessey and her sister, Officer Ryan and the rest of the “morals squad” arrested a total of 22 women for suspicion of STIs. Of the 22 women arrested, 16 of them were released that night, and like Margaret Hennessey, were likely issued orders to appear in court the following day.

Six of the women were kept in detention overnight, not allowed to speak to or contact anyone as to their whereabouts or why they were there. Only one woman of the 22 tested positive for STIs. The local paper, the Sacramento Bee, wrote how “out of twenty-two suspects subjected to an examination, the police were justified in arresting but one woman.” In reality, the police weren’t justified in any of the arrests they made that day or any following it.

Suitable punishment

A major problem with the American Plan was the vague idea of “reasonable suspicion” that granted officers the ability to arrest any woman they wanted for pretty much any reason. Archives show records of officers who arrested women for things like sitting alone at a restaurant, being out with a man, walking down the street in a suspicious way, and for no recorded reason at all.

Women who were detained, examined, and tested positive for STIs were subject to treatment that was poisonous to their bodies. Most often, these women were injected with mercury and forced to ingest arsenic-based drugs as those were the common treatments for gonorrhea and syphilis at the time. In some cases, these women were sterilized against their will or without their knowledge.

Not completely gone

The American Plan lost its legs in the 1970s after decades of political turmoil surrounding the program. Multiple women came forward about their experiences and took their cases to court. For those who were not deemed infected, they often won their case. For those who were deemed infected and had undergone treatment, their cases were justified in the eyes of the legal system and won nothing but public awareness of what was happening to women across America.

More from us: Ridiculous Advice Women Were Given in the 1950s

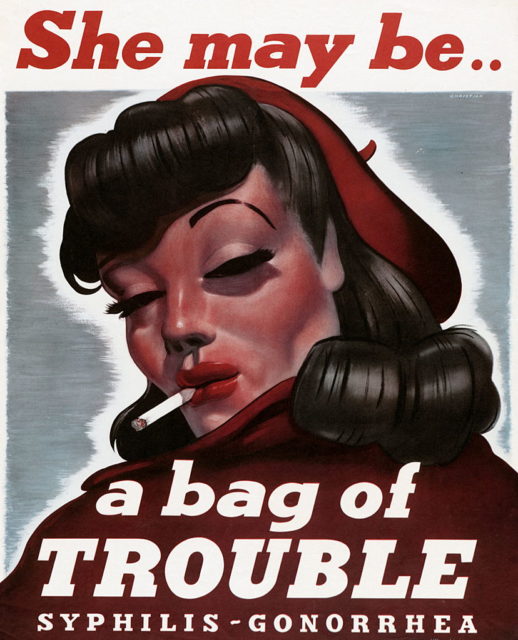

Eventually, the undercover surveillance officers who worked for the American Social Hygiene Association that were employed to flush out infected women pivoted their efforts towards more public-facing campaigns that caused less public backlash. None of the laws passed for the American Plan were ever fully repealed, and they still remain in the veins of the American legal system today.