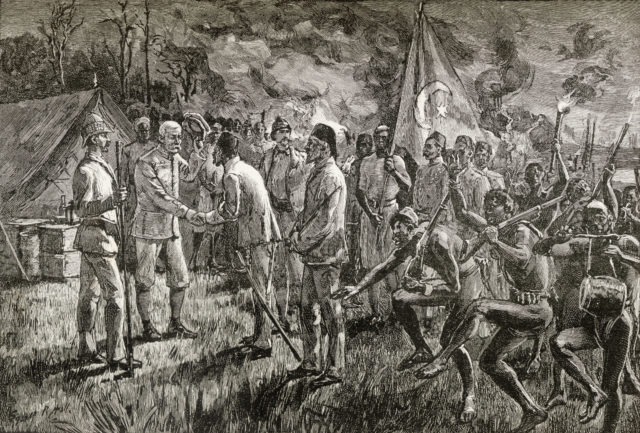

This whole scenario is a mess. It first came out in 1888, and it has remained a scandal even today. It all began when an expedition to rescue Emin Pasha, Governor of the Equatorial Province in southern Sudan, was organized. He was being held up by Mahdists, and Henry Morton Stanley was sent to retrieve him, along with an accompanying crew.

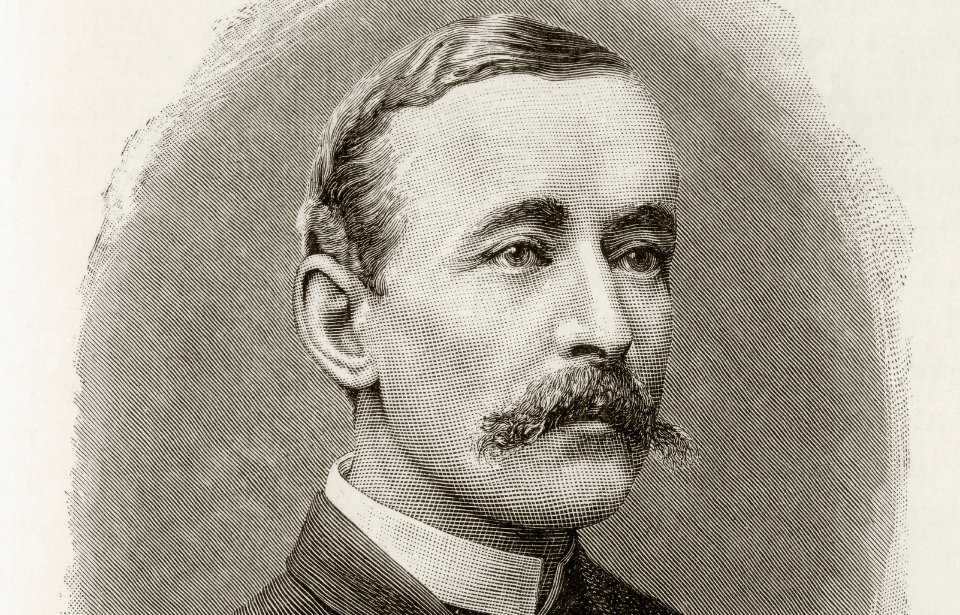

James Sligo Jameson, the grandson of John Jameson of Jameson Whiskey, was one of the people who joined the expedition and was more concerned with exploring new colonial territories in the Congo. While on this expedition, Jameson witnessed and recorded an event that, thanks to opposing reports, would tarnish his name.

It cost six handkerchiefs

The scandal claims that Jameson paid for a slave girl to be murdered, mutilated, and eaten. Now, the murder and mutilation did occur. Jameson wrote an account of it himself, but so did an interpreter who was on the expedition with him. The two accounts oppose one another and so the motivation for what happened is where the confusion lies.

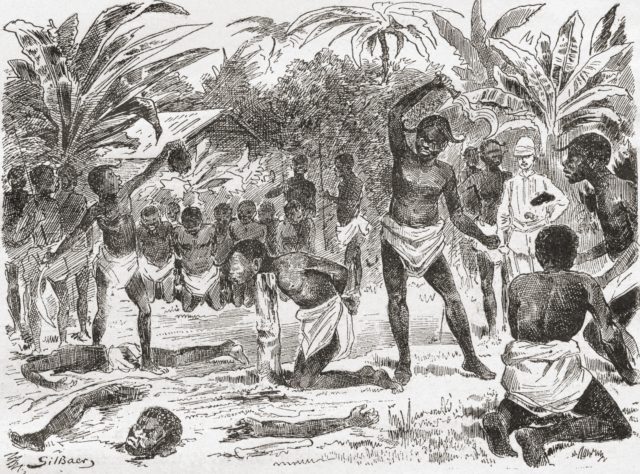

Jameson’s account says that during a conversation with a fellow traveler, he questioned whether rumors about cannibalism in the region were true. The gentleman told Jameson that if he offered something, he could see it happen. Thinking it was a joke, he had someone fetch six handkerchiefs for him and handed them to a man who brought with him a girl of about 10 years old.

Mutilation and cannibalism

The man who brought the girl proceeded to stab her twice, and she fell on her face. Then, three men appeared, ran toward her body, and began to cut her up. Her head was eventually removed and each man took the pieces of her body that they claimed to the river to wash them off. Jameson’s account says the girl never struggled and only uttered a sound when she fell to the ground. In his letter to his wife, he said that this event was “the most horribly sickening sight I am ever likely to see in my life.”

Assad Farran’s first statement and retraction

Before Jameson’s account became public, distinguished interpreter Assad Farran made a statement saying that Jameson used his wealth and power to ‘buy’ the young African girl and wanted to witness her murder and mutilation to satiate his own perversions and curiosities. This statement was very quickly released in the London Times.

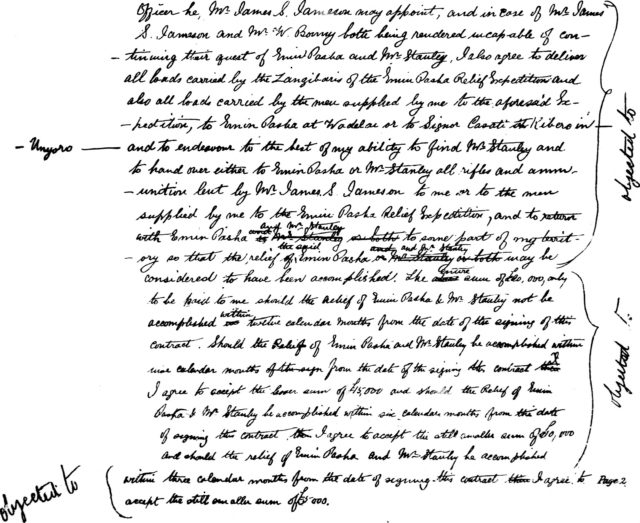

In 1888, Jameson died of hæmaturic fever, a type of typhoid fever, while in Bangala at the young age of 31. Before he died, however, he was aware that Farran had made those statements against him. He wrote to his wife, asking her to stop the claims Farran made because they were false. Jameson said he never thought anyone would go through with the act of cannibalism and was horrified to see it for himself.

Confusingly, Farran retracted his statements almost as quickly as they were published. A Conservative Member of Parliament, William Burdett-Coutts, came forward to say that Farran had admitted to him personally that he had fabricated the allegations against Jameson and later witnessed Farran sign the retraction himself.

Farran makes another statement

Apparently, Farran wasn’t done with Jameson. In 1890, Farran came forward with another statement that retracted his retraction. His second statement was not as severe, but still claimed that Jameson was very eager to see the young girl being murdered and mutilated, and that he sketched the whole thing while it happened.

Jameson did sketch the event, but says he only did so after he retreated back to his home. He claims he had no sketching equipment on him when the event occurred and therefore could not have drawn it at that time, even if he wanted to, which he says he did not. Because of the opposing accounts, the time that Jameson sketched the event remains unclear.

Ethel Jameson tries to clear things up

Jameson’s wife, Ethel, tried to clear his name by having his letters and Farran’s retraction published in the newspaper. Unfortunately, the information in both pieces contradicts each other and so the whole situation became even more confusing.

In the original retraction statement, Farran says that the handkerchiefs in question had no relation to the event that occurred. However, Jameson’s own account clearly states that the whole reason the event occurred in the first place was because he did hand the handkerchiefs over. They had a direct link to the event that occurred.

More from us: Meet Robert Ressler – The Man Who Coined The Term ‘Serial Killer’

Farran making the statement claiming Jameson did this out of perversion, then retracting it, then coming forward again saying it actually was true, made this whole situation extremely scandalous. Ethel having both Jameson’s account and Farran retraction published side-by-side did not help in clarifying the truth. Still today, it is unclear why and how the murder and mutilation of that 10-year-old girl actually occurred.