What on earth could Rasputin have to do with that ‘fictional’ disclaimer before films? Well, a lot, actually. It is because of his life and death that production studios are terrified of being sued for defamation and want to make sure that audiences know what they are presenting should not be taken as historical fact – even if it is. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) steered a little too far from the truth and it cost them dearly. It was a mistake that many production companies have since tried to avoid.

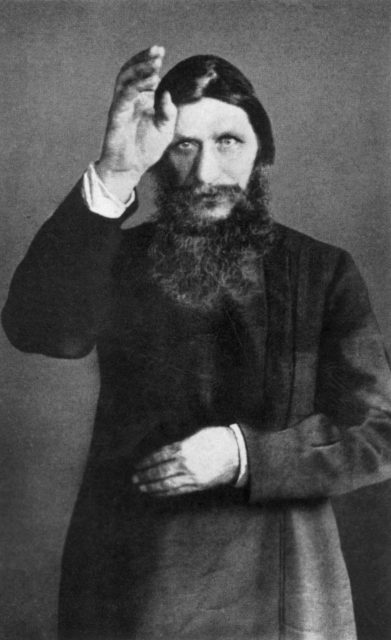

The death of Rasputin

As history books tell us, Rasputin was difficult to kill. His eventual demise came at the hands of Prince Felix Yusupov, who was married to the tsar’s niece, Princess Irina Alexandrovna. Yusupov, along with other disgruntled aristocrats, devised a plot to get rid of the mystic who had grown too close for comfort to the Russian Imperial Family.

Their first attempt was unsuccessful. In 1916, Rasputin had been invited to Yusupov’s palace where they had laced cakes with cyanide. Strangely enough, the poison seemed to have no effect on the mystic. Later that evening, Yusupov resorted to shooting Rasputin with the help of fellow aristocrat Vladimir Purishkevich, who followed up with four shots to his back.

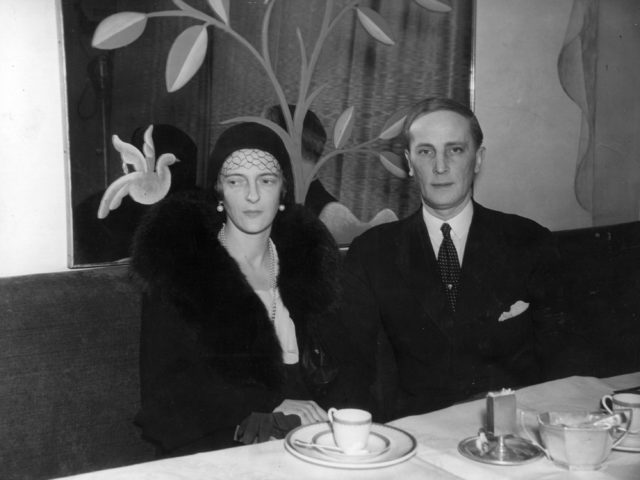

As punishment for his crime, the tsar exiled Yusupov and his wife, Princess Irina, from the country without a penny to their name. They moved to Paris, which, unbeknownst to them and the tsar, would keep them from being killed alongside the rest of the Imperial Family in the Russian Revolution.

MGM came out with a new film

In 1932, MGM made a film titled Rasputin and the Empress that involved the killing of Rasputin. This film was expected to be a hit, as MGM was able to hire all three of the Barrymore siblings (who were huge stage and silent film actors) to star as the main characters. Lionel was Rasputin, Ethel was the tsarina, and John was “Prince Paul Chegodieff.” This film was the first (and only) time all three starred in the same film together, so it was a pretty impressive cast that was sure to draw in large crowds.

In the film, Prince Paul Chegodieff’s wife, Natasha, is a supporter of Rasputin. Rasputin was not trusting of Chegodieff and uses his wife to attack him. Rasputin places Natasha under a hypnotic spell and assaults her so that she admits she is no longer fit to be a wife. The film made it very obvious that Prince Paul Chegodieff was a representation of Yusupov, which naturally made Natasha a representation of his wife, Irina. They even made Natasha the same age and dressed her in a gown that looked oddly similar to one Irina had once worn.

MGM was really excited about the plot they had come up with. They found it a lot more interesting and believed audiences would too. There was one skeptic, however, a researcher for the company, who warned them that the factual discrepancies between the film and real-life could cause them a lot of trouble. Not heeding this warning, they fired her and went on with the film.

The lawsuit

After they were exiled, Yupurov had written a memoir about his crime, since he was very proud of having killed Rasputin. Unfortunately for him, this memoir prevented him from coming forward with a libel case against MGM after hearing the plot of the film. As he was the one to actually commit the murder, that information was not necessarily presented as false by the production company. What was presented as false was the depiction of Irina as Natasha. Irina had never met Rasputin, so the idea that her character in the film not only met and supported him but was hypnotized and raped by him was clear defamation of her reputation. So she sued.

MGM made the mistake of prefacing the film with a statement that basically told audiences to trust the film as historical fact. They said, “This concerns the destruction of an empire… A few of the characters are still alive – the rest met death by violence.” Considering that Yusupov and his wife were the only two surviving members of the Imperial court, it was not difficult for people to deduce that Prince Paul was Yusupov and Natasha was Irina. At this point, MGM had done virtually nothing to protect themselves against this lawsuit, and Irina won the case, receiving £25,000 ($2.4 million by today’s standards). The film was taken out of circulation for years and unsavory scenes were removed from the film as further punishment.

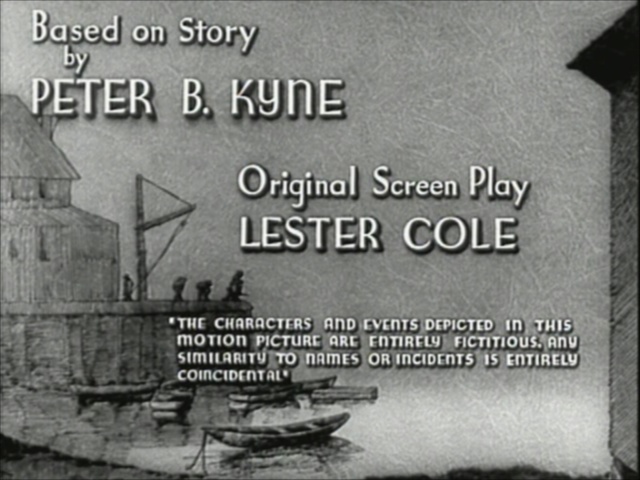

A disclaimer would suffice

The justice of the case had actually mentioned that if they’d presented a disclaimer that did the exact opposite of what their original one had, they would have stood a much better chance in court. That was the slap on the hand MGM needed to make sure they were protected from further lawsuits. From then on, they placed a disclaimer at the beginning of every film stating that what they presented was fiction and should not be taken as fact in any way.

They weren’t the only production company to do so. The lawsuit lost by MGM cost them a pretty penny, and fellow studios did not want to risk that happening to them. Soon, every film had a disclaimer at the beginning reminding the audience that what they were about to watch was not real. Even films that were fact, like Jake LaMotta’s biopic Raging Bull, were labeled as entirely fictitious although, in this case, the man himself and his memoir are cited as consultants on the film.

More from us: The Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd Moon Movie That Was Lost In Space By MGM

No one was taking any chances with libel cases. It was only after Yusupov died in 1967 that studios began to ease up on using the disclaimer before every film. Still, you often see it today.