When President James A. Garfield was shot in the back, inventor Alexander Graham Bell took it upon himself to get involved with his potential recovery. He invented a device to help detect the bullet lodged in the president in an effort to try and save the president’s life.

Garfield gets shot

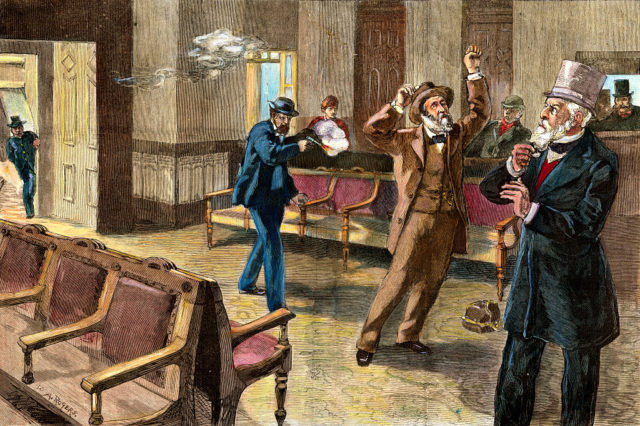

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was shot in the back. He was entering a station waiting room in Washington D.C., intending to catch a train to begin his summer vacation. His assassin, Charles J. Guiteau, came up behind him and fired two shots. The first had only grazed the president‘s shoulder, startling him. Guiteau was quick to fire his second shot and it landed right through the president’s back.

Garfield did not die that day in the station waiting room. He would experience both improvements and declines in health and struggled with his injury for months. Guiteau was arrested on-site by a nearby police officer and was later hung for his crime in June 1882.

Alexander Graham Bell gets involved

The attempted assassination of Garfield, as well as his recovery from the shot, was highly publicized in newspapers. Alexander Graham Bell, who was famous for having invented the telephone, read about the situation and was absolutely appalled. He volunteered himself to the White House to help with the president’s recovery.

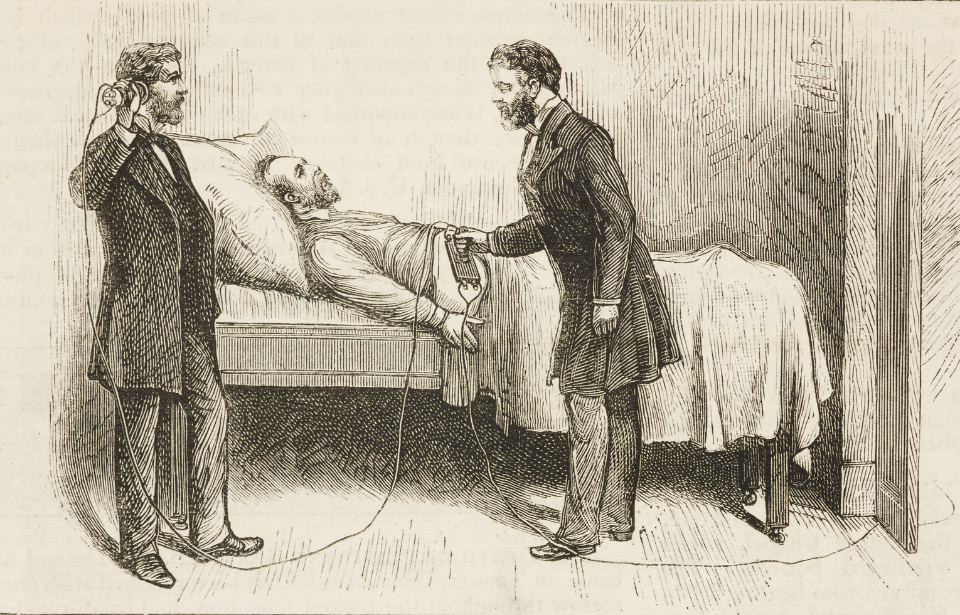

Based on an induction-balance device invented by his friend and fellow inventor David Hughes, Bell developed what can be considered the first rudimentary metal detector. It worked with a lot of the same features as Bell’s telephone, and its use on the president marks the first attempt to locate a bullet in the human body without the use of surgical procedures.

It used a battery and several metal coils attached to a wooden platform to generate an electric field, and when one coil was passed over the body, if it detected metal, it would respond with a clicking sound to an earpiece.

Both attempts failed

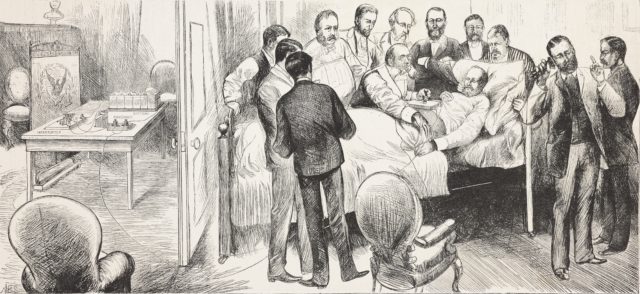

Bell had made sure to test the device before bringing it to the White House by shooting rounds into a wooden board, then animal carcasses, and using the coil to scan for metal. These tests were successful, and he made sure to test it on Civil War veterans who still had known bullets lodged within them to ensure the device could be useful.

When he arrived at the White House, he found the president to be very weak and grey, and commented that it was like he was already dead. When they began the first attempt to search for the bullet, there was some loud static caused by the addition of a condenser to the device. The noise made it near impossible to hear the clicking sound that would alert the listener of the detection of metal. The first attempt was a bust.

After tinkering with the device to fix the issue of the condenser, Bell returned with the president’s physician, Dr. Bliss, who took charge of the scanning. You could’ve heard a pin drop as not a single word was spoken during this attempt. Garfield was turned onto his side, and Bliss ran the coil down the president’s spine. Bell noted how he thought it strange that Bliss would only search his back, considering that they had all expected to find the bullet lodged in the abdomen somewhere on his front side.

Dr. Bliss was wrong

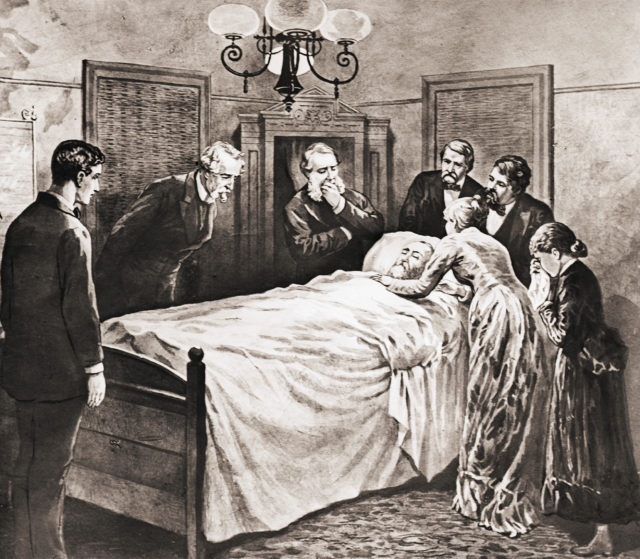

Ultimately, they were unable to find the bullet and Garfield continued to try and recover while the bullet was still lodged somewhere in his body. He was taken to the New Jersey seaside on September 6, where he seemed to be recuperating nicely. But on September 19, 1881, Garfield died from an infection and internal hemorrhaging.

During the second attempt, Bliss had become convinced that the bullet was located somewhere on the left backside of the president and he was not willing to entertain the idea that it may be lodged elsewhere. Because of this, many believe that Bell’s device would have actually been successful – it just wasn’t being used to look in the right places.

More from us: The Haunting Final Words of 15 US Presidents

After Garfield died, his body was autopsied. The autopsy showed that Bliss was incorrect in his assumption. The bullet was found on the left side of his chest, in the exact opposite position where Bliss had insisted it was.