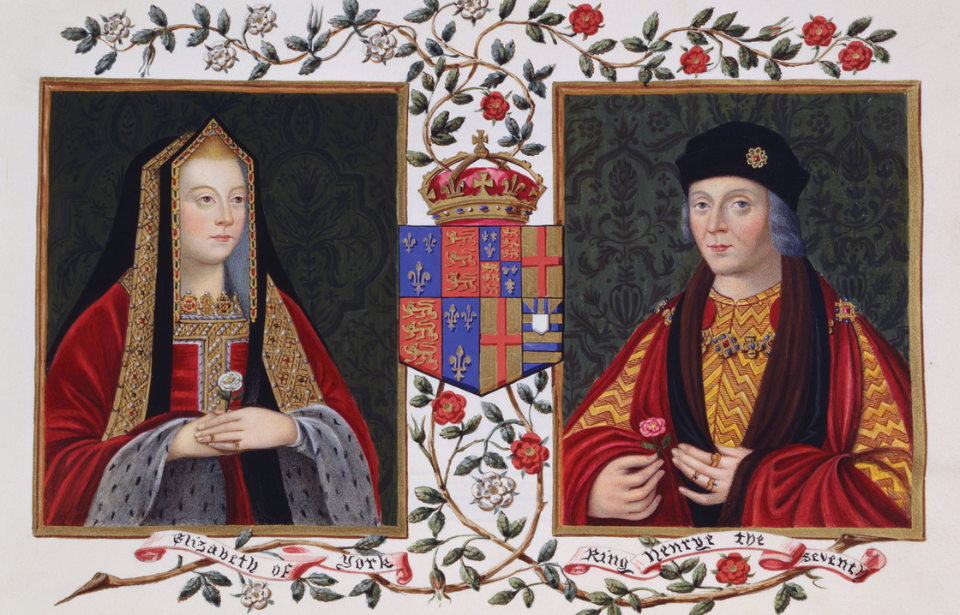

Elizabeth of York, born in 1466, was the eldest daughter of King Edward IV and Queen Elizabeth. She was a devoted wife and mother, a beautiful and charming Queen, and accomplished many things in her short life.

Elizabeth of York was betrothed multiple times

By age nine, Elizabeth had already been betrothed twice, once to her cousin George Neville, which was called off after his father supported an opponent of Edward, and then again to the Dauphin of France, Charles. This was a very exciting betrothal as the title of Queen of France was the second-highest in Europe, topped only by the Holy Roman Empress. An arrangement like this could only come from political origins, and this one was the result of the 1475 Treaty of Picquigny. Edward was invading France with what was at the time the largest army to ever leave England. He planned to do so in cooperation with the Duke of Burgundy, but the Duke was not prepared for the invasion and the French were willing to buy Edward out of invading. Over time, King Louis XI decided not to follow through with the arrangement and instead made other plans for his son’s marriage, leaving Elizabeth behind.

King Richard III forces Elizabeth into sanctuary

Edward’s brother, Richard, wanted the throne. However, when Edward suddenly died in 1483 at the age of 40, the crown was passed to his son, making him King Edward V. At only 12 years old, Edward was unable to assume the throne entirely, and so Richard became his Lord Protector, which essentially gave him temporary power behind the throne until Edward became of age. During this time, rumors circulated claiming that the marriage between Edward IV and Elizabeth was illegitimate. Elizabeth took her children and fled to the sanctuary of Westminster Abbey, and eventually, those rumors became official, making her children bastardized. It is believed that when Richard had called for Edward’s two sons to come out of safety, he had them both killed, making him King Richard III. He reigned until 1485.

Henry Tudor planned to marry Elizabeth of York

With the assumed murder of her two brothers, Elizabeth became the rightful heir to the throne. An opposer of Richard, Henry Tudor, was aware of this as he had been in communication with her mother and she had urged him to do something about it. Eventually, he declared that he would defeat Richard and become king, and would then take Elizabeth as his wife. Technically the two were third cousins, but this was overlooked as their betrothal played a pivotal role in the Wars of the Roses – the dynastic civil wars between the houses of Lancaster and York. Their marriage could cast aside the feud and create a new Tudor dynasty.

Henry was successful in his quest to defeat Richard, doing so at the Battle of Bosworth. He was sworn in almost immediately, becoming King Henry VII. Not long after his coronation, he sent for Elizabeth, but the issue still remained of her bastardization. The two had to wait until the bastardization was reversed, and once it was, the two were quickly married. Their marriage had even more importance than its symbolism in the Wars of the Roses – Elizabeth had a more legitimate right to the throne than Henry did. As such, his marriage to her secured his place on the throne, though he would never admit her importance to this security.

She shared an emotional connection with King Henry VII

Despite their marriage being arranged and tactful, the two were actually quite compatible. They were affectionate with one another, always giving each other gifts, and they appeared to have an emotional connection. Elizabeth was a beautiful, loving wife, who always placed her husband’s interests first. Because of this, it did not take long for Henry to find a deep respect for his wife despite her connections to powerful York diplomats. She proved where her loyalties lay, time and time again, which undeniably gained her the unwavering trust of her husband.

The role of a late medieval queen was largely symbolic and she was mainly there to keep up appearances. For this reason, one could easily assume Elizabeth had little to no influence over political matters. In fact, there is a good chance she did have very little to do with political affairs, as she chose to keep out of politics… for the most part. There is evidence that she may have had more political involvement than history books lead us to believe, as outside persons showered her with gifts. Clearly, it was believed that she was someone with whom favor could serve a purpose.

King Henry VII truly trusted Elizabeth of York

It seems that she had a soft influence over her husband, resulting from their loving connection. Where Henry may not have turned to her in decision-making matters, he did confide in her matters of the highest level of secrecy. For instance, she had taken charge of her brother-in-law, William Courtenay’s, children and helped her sister to care for them. About a month after she began to help her sister, William was imprisoned in the Tower of London on a charge of treason. Elizabeth knew beforehand that her husband was not only aware of William’s treasonous activities, but she also knew of Henry’s intention to remove William from the family and have him imprisoned. This information would have been a confidential state secret, not something a late medieval queen would need to concern herself with.

Elizabeth of York took matters into her own hands

Elizabeth was not only loved by her husband, she was also loved by her people. She performed her queenly duties with charm and appeal, and she won popularity from her people by being directly involved with charity and showing a genuine concern for the poor. In one recorded instance, Elizabeth had received a complaint from a Welsh tenant that she did not even bring to the attention of her husband, which was typically expected of her to do. Instead, she listened to the complaint which stated that Henry’s uncle, Jasper Tudor, was too heavy-handed. To this, she had written a sharply-worded letter to Jasper herself. Apparently, this approach had achieved the results she was hoping for, and further proved her subtle power and influence in the kingdom. Beyond this, any additional influence that Elizabeth may have had went largely unrecorded.

She was deeply concerned with her children

Henry VII and Elizabeth had eight children together, four of which did not survive infancy. Their eldest son, Arthur, died in 1502 from the “sweating sickness” shortly after his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. He was the heir to the throne and was only 16 years old when he died. His death brought deep sadness upon Henry and Elizabeth, and the two comforted each other. At one point, Elizabeth had become inconsolable to anyone but the king himself, proving further that their marriage was affectionate and they did support each other emotionally.

Some of the other areas where Elizabeth publicly concerned herself included her household, her estates, her court, and her children. In regard to her children, she was directly involved in arranging their marriages, a duty which was expected of her as queen. Her children who survived infancy had received prestigious betrothals, with her daughter Margaret becoming the Queen of Scots and her daughter Mary becoming the Queen of France. Henry VIII went on to become king, and notoriously went on to marry several times.

Elizabeth of York died after giving birth

It is believed that Elizabeth had become pregnant with their eighth child in an attempt to produce another son, preparing for the chance that their son Henry might die before her husband, leaving the Tudors without a male heir. She gave birth to the child in the Tower of London, and died shortly afterward on February 11, 1503. It was her birthday and she was just 37 years old. The child, a girl, did not survive long after the birth, dying shortly after her mother.

More from us: The Fierce Medieval Queens History Has All But Forgotten

Elizabeth was given a grand funeral. Her body was carried in a beautiful hearse to the City of London with eight women riding on white horses following as part of the procession. Because her death was sudden and unexpected, she was temporarily buried in a vault specifically made for her at Westminster Abbey. Construction of the Lady Chapel, intended to house both her and her husband after death, had only just begun. When the extraordinary Lady Chapel was finally complete, she was reburied there and was joined by Henry following his death in 1509.