Old and new worlds collided when American socialites and heiresses, known as “dollar princesses” arrived in the United Kingdom with one goal in mind: to snag themselves a prince.

What began as an appalling phenomenon for the families of British nobility soon became a symbiotic relationship between wealthy American women looking to gain social status and the heirs of old English families who were in desperate need of financial stability. But what happens to love when money isn’t enough?

The lord and the socialite

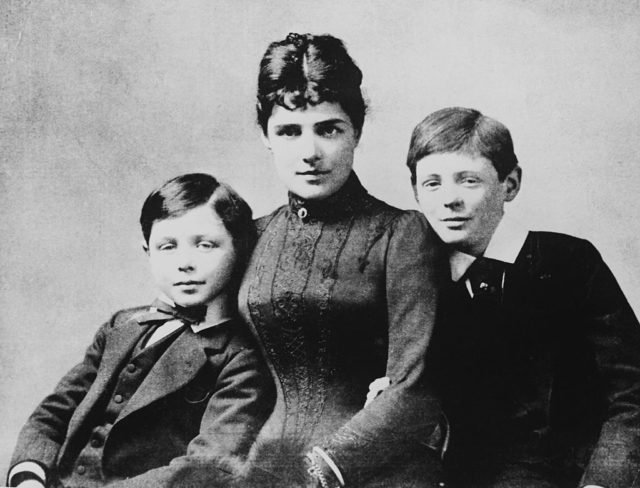

This exact story happened to Lord Randolph Churchill, who announced his engagement to American socialite Jennie Jerome in 1874 – after meeting her three days earlier. Jerome was one of the few tattooed heiresses raised in New York’s high society by her mother, who was one-quarter Iroquois.

Churchill was the first in a long line of nobility to break with tradition and marry someone outside of his social standing. His parents clambered to find ways to break off the engagement until Jerome’s father came forward with a massive dowry in anticipation of her marriage, estimated to be over $4 million dollars today.

Even though Lord Churchill and his wife Jennie were considered an unconventional match, Mrs. Churchill became a favorite amongst the British elite. Even the Prince of Wales, who would eventually be crowned King Edward VII, was “known to delight in her company.” The same year they were married, Lord Churchill and Jennie Jerome welcomed their first son: Winston Churchill – who would become one of the most celebrated British Prime Ministers in history.

Old world, new money

Unfortunately, not every “dollar princess” went on to live a life as charmed as Jerome did with Churchill. The overnight success story of their wedding triggered an influx of American socialites arriving in England hoping to get their own “happily ever after.” Between the late 19th century and the mid-2oth century, hundreds of American heiresses arrived in the UK, injecting billions of dollars into the British economy.

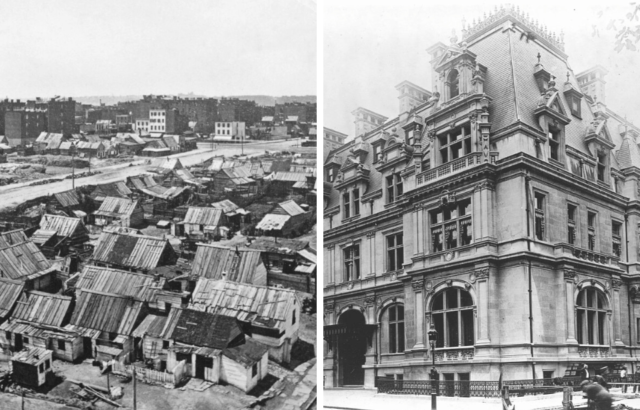

The relationship between American brides and their noble husbands was a lifeline for the foundering British aristocracy. While the Gilded Age was a time of unimaginable wealth, massive mansions, and sprawling urban development for the American elite, the growing agricultural production of grains in the United States robbed the UK of its status as a leading grain production country. Suddenly, stately country manors were surrounded by vacant farms, and once-noble families were left with only their titles and family heirlooms.

While the daughters of America’s new high society had every luxury available to them, they still longed to match their lifestyles to the status of British royalty. In turn, earning the title of Lady or Duchess could increase the social standing of the bride’s family back in America – especially as many “new money” enterprises in agriculture, oil, and mass production struggled to gain notoriety amongst big “old money” names like the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts.

The Gilded Age

If not for the economic and social conditions created by the “Gilded Age“, the “dollar princess” phenomenon might never have been possible.

The Gilded Age first got its name from an 1873 novel by Mark Twain called The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. Twain adopted the term to attempt to describe the period between 1870 and 1900 when social problems were masked by the gilded foil of economic expansion despite “The Golden Age” that was promised following the Civil War.

The upper echelons of society lived every part of their lives dripping in excess: elaborate clothing, huge mansions, high-tech telephones and automobiles, and trips to Europe on luxury liners like the Titanic – some families even went as far as to install solid gold toilets!

As for the working class, life became a drudgery of 14-hour work days in factories, mines, or other hard labor jobs that came with low pay and sometimes permanent health issues. Men, women, and children were all exposed to these horrid working conditions while the men who owned the factories and mines became richer and more powerful by the minute.

Million-dollar duchess

Because of the politics surrounding money, many “dollar princess” marriages were closer to a contractual agreement rather than a joining of two people in love. Many new brides struggled to adapt to life in the “old world,” where day after day was spent pent up in large, dark, and dreary country homes. Nearly every task required a staff of lady’s maids, valets, butlers, and social life could be extremely isolating, as British women mocked the American way of life.

Eventually, “dollar princesses” became so popular that even the British royal family was influenced by the trend. In 1880, heiress Frances Ellen Work married Baron Fermoy, but the couple divorced ten years later. Even though their marriage didn’t last, Frances Work’s great-granddaughter Diana Spencer married a prince of her own, Prince Charles the Duke of Wales.

Another famed loved story gone wrong came from the very top of American high society: Consuelo Vanderbilt, the daughter of wealthy businessman W. K. Vanderbilt – whose fortune would be worth over $1 billion dollars today – married Charles Spencer-Churchill, the 9th Duke of Marlborough, in 1895. The Duke married the young railroad heiress to stop his dukedom and his ancestral home Blenheim Palace from falling into bankruptcy.

In exchange for making their daughter a duchess, William and Alva Vanderbilt offered the Duke of Marlborough $2,500,000 in shares of capital stock from the Beech Creek Railway Company and a 4% dividend guaranteed by the New York Central Railroad Company. In all, the deal would be worth $77 million dollars in today’s money. The couple was also given an annual income of $100,000 for life.

More from us: Here’s How the Royal Family Gets Its Money

Consuelo and the Duke both announced they didn’t love each other, and supposedly the soon-to-be duchess was locked in a room until her father and almost-husband agreed on her dowry. The newlyweds used the money to refurbish Blenheim Palace, where the duchess was showered in jewels – but she was far from happily married. In 1906, the couple separated, they were officially divorced in 1921, and their marriage was annulled by the Vatican on August 19, 1926.