The Battle of Waterloo, the final battle of the Napoleonic Wars, was fought just south of Brussels on June 18, 1815. Both sides suffered significant losses, and there were thousands upon thousands of casualties left on the battlefield at its conclusion. Naturally, one would assume that there would have been some sort of gravesite where these bodies were taken, but current excavations have proven that a large majority of these remains are nowhere to be found.

One professor has a theory as to why these remains may have gone missing. Gruesomely, it centers around the idea that their bones were used as fertilizer.

Contemporary accounts describe mass graves

Shortly after the battle had ended, droves of people made their way to the site. Some wanted to catch a glimpse of what had happened there, others went in the hopes of stealing the belongings of the dead, and some even stole teeth to make themselves dentures. Regardless of their desire to go to the battlefield, some of those who visited wrote about what they saw. There were multiple contemporary accounts that outlined the sheer volume of bodies that were left on the battlefield following the fight.

James Ker, a Scottish merchant living in Brussels at the time, visited the battlefield just days after it had come to an end. He recorded his visit, explaining how there were loads of men lying there, dead or barely alive, and some even died in his arms. Another man, Newman Smith, reported having seen wagons moving the wounded, but leaving far more behind. There was obviously a struggle to remove the dead from the field, likely resulting in mass graves.

Accounts of mass grave burials were also made at the time. One man, James Rouse, sketched the carnage and the cleanup. Sir Walter Scott wrote in August 1815, “All ghastly remains of the carnage had been either burned or buried, and the relics of the fray which yet remained were not in themselves of a very imposing kind.” The narrative from all of these firsthand records, illustrated or written, shows a shift from reports of the wounded and deceased lying exposed on the battlefield to them being buried or otherwise dealt with.

What is unclear is where they were buried. The locations of three mass grave sites indicated by these records, supposedly home to more than 13,000 soldiers who were buried following the battle, are predicted to hold very few human remains.

Tony Pollard theorizes their true location

Several archaeological excavations of the battlefield have been unable to discover mass graves. Professor Tony Pollard of the University of Glasgow has theorized that the locations indicated in the records where the soldiers were buried en masse will likely have little to no remains left there, due to the work of grave robbers. He believes that the contemporary accounts following the battle actually acted as treasure maps for grave robbers to find the graves and begin digging.

Grave robbers would have had to been incentivized enough to begin digging, and mass graves were like the jackpot. Locals would have had vivid memories of the battle that occurred near and around the area and would have been able to easily point out where the graves were located. If mass graves did exist in the locations mentioned in the sources, then Pollard believes it is highly likely that grave robbers saw them as a lucrative opportunity to dig up multiple bodies and use their remains to sell to the fertilizer market.

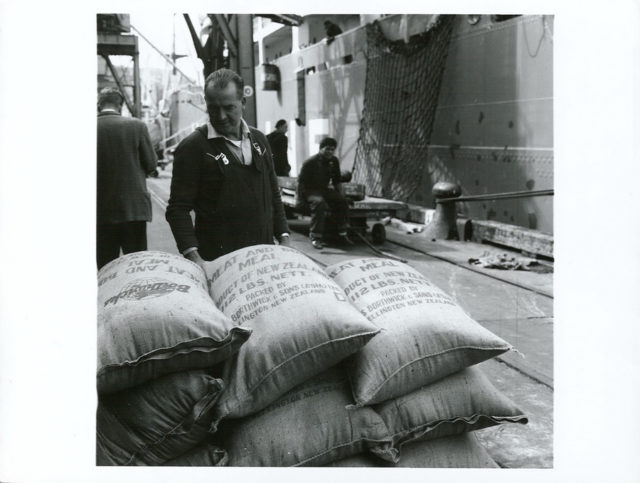

A market for bone fertilizer

Bone meal had proved to be a very important source of phosphate fertilizer during that time period. The bones would be ground into a fine powder and sprinkled into the soil, where they apparently did better as fertilizer than any manure ever could. Bones thus became a commodity that many people were in the market for. A report published in 1822 indicates the existence of a market for bone meal, stating that, “It is estimated that more than a million bushels of ‘human and inhuman bones’ were imported from the continent of Europe into the port of Hull.”

This was not the only account. There were at least three newspaper articles from the 1820s onward that reference the importing of human bones for fertilizer, specifically from battlefields. This gives some substance to Pollard’s theory, offering a valid explanation as to why we are unable to locate the remains of thousands of fallen Waterloo soldiers.

How to prove it

Pollard intends to spend the next several years conducting a geophysical survey of the area, excavating the locations of two of the supposed mass grave burial sites, La Haye Sainte and Hougoumont, mentioned in the sources. He stated, “If human remains have been removed on the scale proposed then there should be, at least in some cases, archaeological evidence of the pits from which they were taken, however truncated and poorly defined these might be.” With his team, he hopes to identify areas where previous ground disturbances have been made, but knows this will be no easy feat.

More from us: 5 Famous Battle Cries and their Meanings

In all likelihood, finding any evidence of previous ground disturbance may be extremely difficult. However, Pollard will still undergo the endeavor, hoping to provide a somewhat more conclusive answer as to what actually happened to the thousands of bodies that were left after the Battle of Waterloo.